A continued lack of female economists might be perpetuated through the books used to introduce the topic to students.

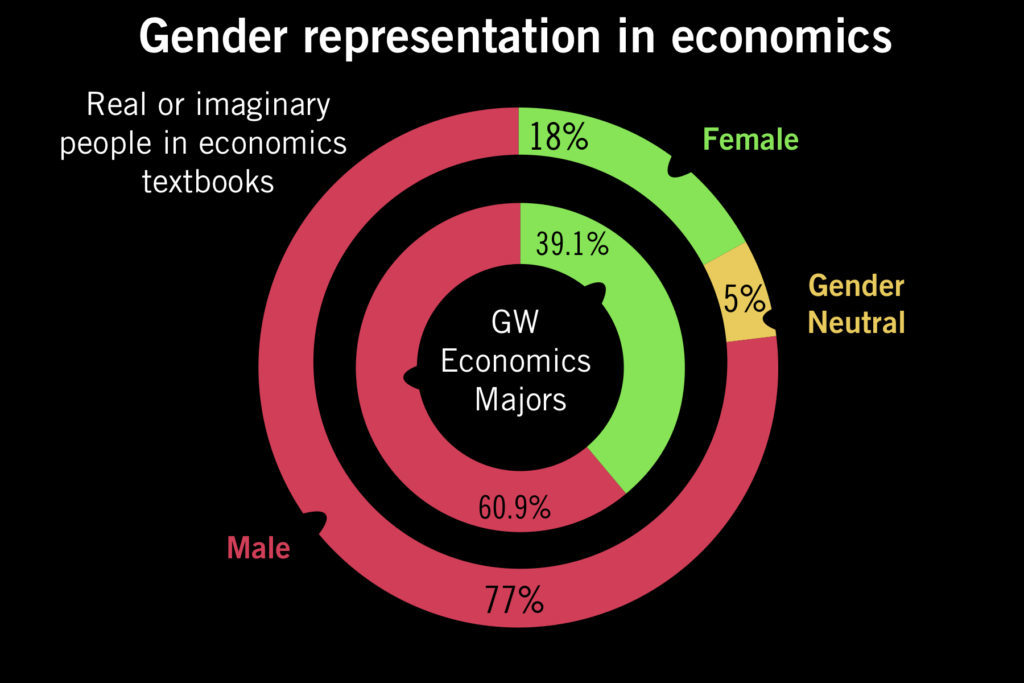

In seven leading introductory economics textbooks, 77 percent of real and imagined people mentioned were male, often in relation to business or policy, according to a University of Michigan study released in January. Most of the 18 percent of female mentions were related to food, fashion or household tasks. Only 11 women across all seven books were mentioned as business leaders.

Economics professors were conflicted on the importance of the study, but some faculty said it reflected a lack of female representation in the field – which can discourage female students from pursuing the major.

Irene Foster, an associate professor of economics who teaches several introductory courses, said the results of the study were not surprising because she and many of her colleagues had already noticed the imbalance.

“There is some bias that way,” she said. “Female students don’t see female representation when they look at the textbook.”

The two most common factors driving women from economics are that textbooks are written with very limited female figures and that course material often seems focused on profit and capitalism, which Foster said can turn female students away from the subject.

To mitigate the issue, she said it is important to highlight women in economics and place a greater focus on how economics relates to the quality of life and society, not just profits.

“We lose a lot of great women who would have come into the field otherwise,” Foster said. “I’ve heard women tell me over and over again that they don’t want to become an economist because they don’t like the approach to the subject and lack of representation, even if they do well in the class.”

This fall, 61 percent of undergraduate economics majors are men, compared to 39 percent women, according to the Office of Institutional Research and Planning.

Foster said she and other economics professors are trying to reduce gender inequality by encouraging one-on-one conversations between students and professors and inviting young female economists come to classes to speak with students. Last year, she said a female alumnus working at the Federal Reserve came to her class to speak about why she was interested in economics and the struggles she faced.

“Having someone who was younger come in and teach the class and even talk to the class for 15 minutes, that made all the difference,” she said. “Immediately all the girls in the class were engaged.”

Another study from four universities released in January found that perceived gender biases are the primary criterion women use for selecting a college major. The study found that if women didn’t worry about gender bias when picking a major, they might be more inclined to choose fields like economics that lead to higher-paying careers.

Mohammed Meraj Allahrakha, an economics lecturer, said the gender imbalance in economics and finance is a problem that goes beyond textbooks and is more about the norms of male-dominated career paths.

“I used to think it was because stupid middle school teachers would tell young girls that they weren’t a ‘math person,’ effectively annihilating any self-confidence they would have, but looking at the number of women in STEM majors, I realized that can’t be it. It’s a cultural problem of economics and finance,” he said.

The University of Michigan study found that in mentioning real-life economics, males outnumbered females 12 to one in the textbooks. Anthony Yezer, a professor in the economics department and director of the Center for Economic Research, said the imbalance was reasonable because the “people responsible for the great advances in economics” thus far have primarily been male.

“If we are to teach the great ideas of economics, then we need to cover the intellectual history which, thus far, has been male,” he said.

Yezer said compared to the number of female students the textbook may be underrepresentative, but considering only one woman has received a Nobel Laureate in Economics – compared to 78 men – women in textbooks are actually overrepresented.

While most historical economic figures are men, the textbook study found that even when considering only imaginary people, 59 percent of gendered mentions were of men, compared to 26 percent women.

Yezer said the textbook he uses is co-authored by a woman, something no student has ever asked him about. He added that he doesn’t feel gender bias is the major problem holding students back from succeeding in his course.

“The major problems in teaching principles of economics to freshmen are that students have not mastered basic algebra and geometry,” he said.