Updated: Jan. 29, 2018 at 3:15 p.m.

Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Editor

Source: Office of Institutional Research and Planning

Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Editor

Source: Office of Institutional Research and Planning

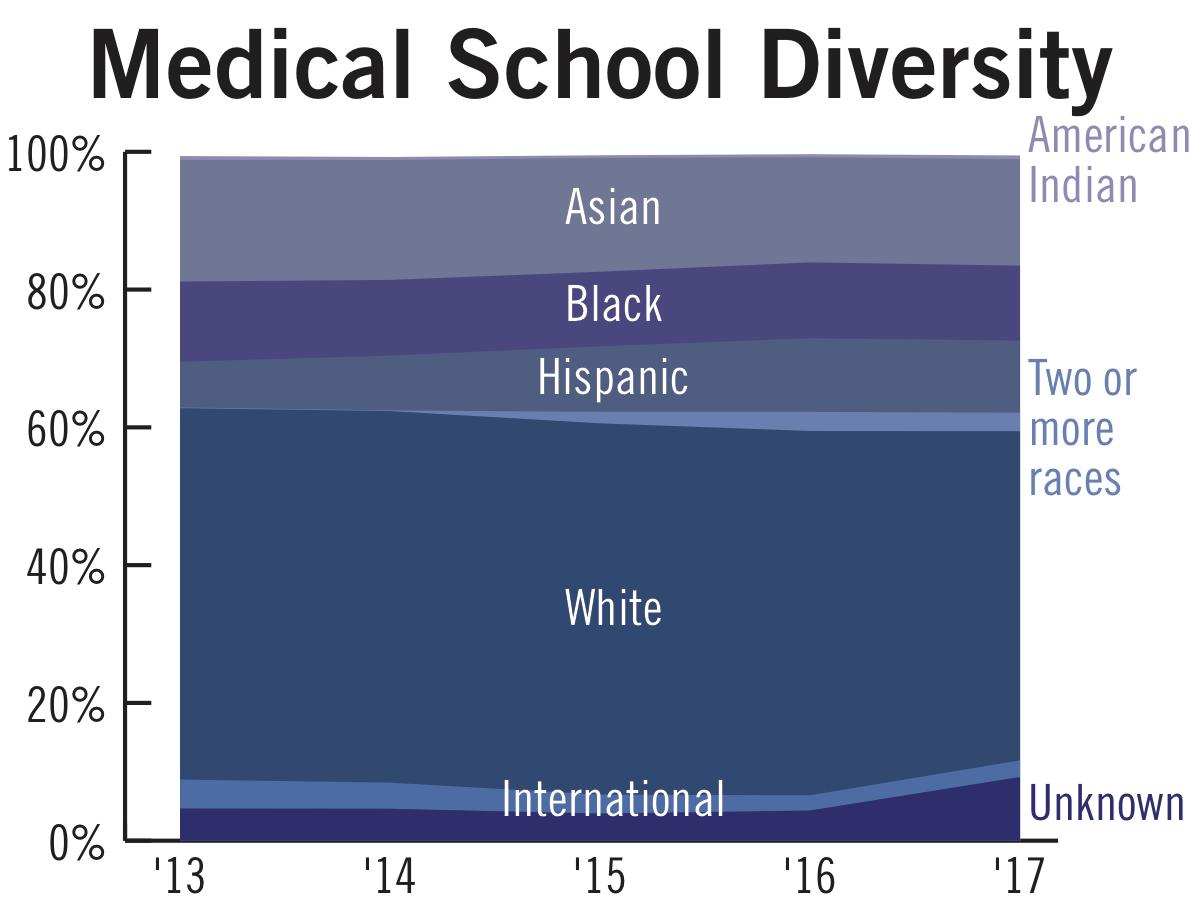

More than four years into a drive to diversify the medical school, officials say they are enrolling an increasing number of students from underrepresented backgrounds, but the percentage of racial minorities at the school has largely flatlined.

After hiring its first diversity-focused administrator, medical school officials and faculty said the school has made a major effort to promote diversity by hosting special events and increasing outreach in diverse communities. But experts say diversifying medical schools remains a nationwide challenge as the steep cost and rigorous academic standards required to attend top schools still pose major barriers to many students.

In 2013, the medical school hired Yolanda Haywood as its first associate dean for diversity, inclusion and student affairs, to oversee the school’s efforts to increase diversity.

Haywood said the medical school works to bring in speakers and host discussions – sometimes based on current events or holidays like Martin Luther King Jr. Day – to address diversity. She said about one-third of MD students now meet the school’s definition of diversity, which includes underrepresented minorities as well as economically disadvantaged and first-generation college students.

The medical school has launched several pipeline programs geared toward engaging high school students in careers in medicine, including Upward Bound and the DC Health and Academic Prep Program – initiatives targeting diverse communities in the D.C. area, she said.

Despite the diversity push, between 2013 and 2017, the black student population at the school decreased from 11.7 percent to 10.9 percent. The percentage of Asian students also declined by more than 2 percentage points, according to data from the Office of Institutional Research and Planning.

Yet over the past five years, the percentage of Hispanic students nearly doubled and last year, non-international white students were the minority at the school for the first time since 2008.

Haywood said the school’s efforts are not based only on increasing representation from certain races or ethnicities, but designed to include all underrepresented populations.

“We do not measure our success by ‘quotas’ or ‘numbers,’ but focus on building and maintaining an inclusive community,” she said in an email.

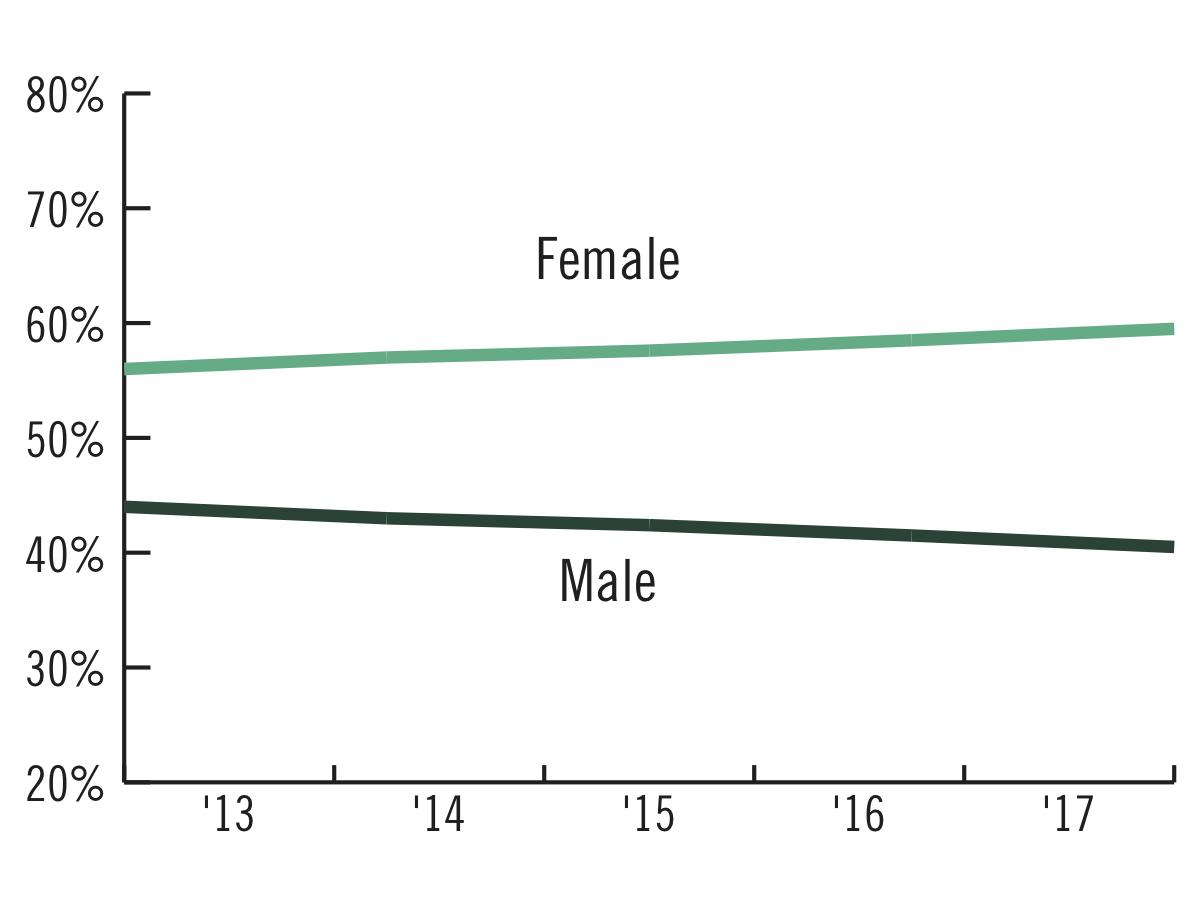

Jehan El-Bayoumi, a professor of medicine, said diversifying the medical school’s student body on the basis of ethnicity remains a challenge, but the school is leading in efforts toward gender diversity. She said the school has a strong track record of enrolling women, who have been the majority at the school for the past two decades.

“The rest of the country is catching up with that,” she said.

Since 2013, female enrollment in the school has increased by almost 2 percentage points, and women have comprised about 60 percent of the school for the last decade. This year, for the first time, more than half of students entering medical schools nationally are women, according to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

El-Bayoumi said the medical school needs to focus diversity efforts both at the student and faculty level, encouraging faculty to promote diversity and inclusion in classroom discussions.

Hispanics make up about 1.6 percent of faculty in the medical school, blacks make up 5.8 percent and Asians are 12.5 percent as of fall 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Women make up a little less than half of faculty at 45.7 percent, according to institutional data.

“Diversity is not just the students,” she said. “If we are going to have diversity – and meaningful diversity – it really has to be at all the levels.”

El-Bayoumi said diversity has been an issue in medical schools across the nation, specifically private medical schools, where students often have to pay more than $50,000 a year in tuition.

“Like most medical schools, GW is challenged with that,” she said. “But, I know the priority for Dean Jeffrey Akman is to really assure that we are improving in those numbers and indeed there have been more people of color, LGBTQ faculty that have been appointed to leadership positions.”

Randi Abramson, an assistant clinical professor of medicine, said diversity in her field builds trust and familiarity between doctors and their patients because doctors should represent the communities they are serving.

“Medicine is a kind of art and science combined and part of art and part of science is that you have differing opinions and perspectives looking at the same exact problem,” Abramson said. “We need all perspectives at the table, we need a really big tent to include everyone and their different perspectives that they bring.”

The medical school has aimed to increase student diversity through a handful of pipeline programs in states around D.C. – like the high school academy at T.C. Williams High School in Alexandria created last fall – where students can take college courses designed by faculty in the medical school.

Experts said schools should expand high school pipeline programs and that investing in a diverse admissions staff can help a school improve its effort to enroll students from different backgrounds.

Sandra Quezada, the assistant dean for admissions at University of Maryland School of Medicine, said enrolling a diverse group of students often starts with encouraging students from underrepresented backgrounds in the admissions process, which could mean collaborating with more community partners to engage younger generations from diverse backgrounds in medicine.

“They should have a diverse admissions committee and group of interviewers who are trained in unconscious bias,” Quezada said in an email.

Virginia Bishop, an assistant professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University, said medical schools like GW should consider making policy changes so that the admissions process doesn’t unintentionally give preference to students from less diverse backgrounds.

“Until institutions truly understand that our present policies give preference to the white and privileged in being accepted into our schools of higher learning, we will always have a deficit in intellectual property,” she said.