Updated: November 8, 2017 at 1:00 a.m.

As the international student population continues to swell, top officials want to attract students from more places around the world.

A group of officials and faculty conducting a broad self-study of the University found that while GW had made “significant strides” in enrolling international students in recent years, the “population of international students is not as geographically diversified as hoped.” The group published the recommendations from the self study late last month.

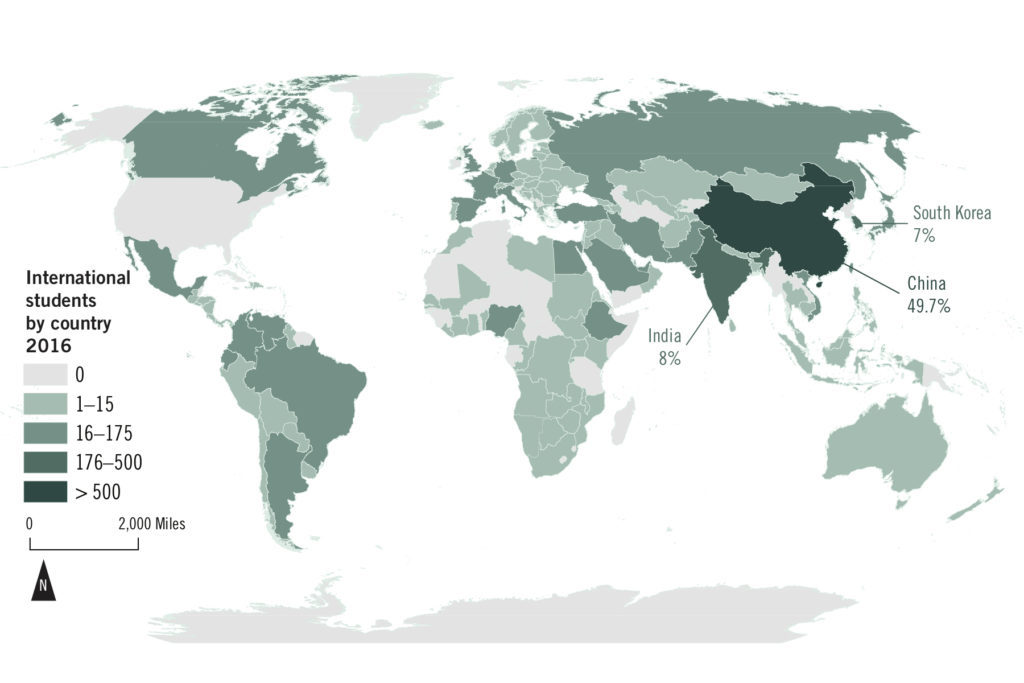

While attracting international students has been a major University goal over the last several years to boost diversity and generate revenue, the study found that too much of that growth has been focused on countries like China and South Korea, where GW has made a major play to recruit students.

In 2016, the most recent year for which institutional statistics are available, almost half of the total international student body at GW came from China. Eight percent was from India, 7 percent from South Korea and nearly 4 percent came from Saudi Arabia. The remaining 31.5 percent came from a combined 135 other countries.

Students and faculty said bringing in more students from different countries across the globe adds new perspectives to campus. But some were skeptical that such a plan could succeed because students from underrepresented countries either look to study at more competitive universities or are deterred by GW’s roughly $70,000 sticker price.

Laurie Koehler, the vice provost for enrollment management and retention, said the geographic diversity of international students is an area of focus for the University because many countries only send a “handful” of students to GW. She said so far this semester the University has held recruiting events in 51 cities in 32 countries or territories across the globe, excluding China.

“Enrolling and graduating a student population that includes international students from around the world will help all of our students appreciate and understand diverse cultures,” Koehler said in an email.

Koehler pointed to partnerships with groups like the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission, a Saudi government-launched agency that helps Saudis studying in the U.S. adjust to American culture and education, and the Tibet Fund, which sponsors Nepalese and Indian students of Tibetan heritage at U.S. universities. The University also partners with other universities around the world to recruit international students from different countries, Koehler said.

She said some of the programs are designed to inform international high school students about studying in the U.S. and some target current college students for American exchange or graduate school programs.

“Building on these partnerships, collaborations, exchanges and other international efforts, GW aims to prepare all of our students to live, work and thrive in an interconnected and global society,” she said.

Recruiting international students has been a top University priority in recent years. In 2013, officials said they wanted to double the percentage of undergraduate international students to 15 percent and international graduate students to 30 percent by 2022. At the same time, officials have also explored new ways to make resources like career networking and meetings with advisers in the International Services Office available to the international student community on campus.

In 2016, the international undergraduate and graduate student population was 10.8 and 18.5 percent of the total student population, respectively, according to institutional data.

Kaajal Joshi, an international student from India and the executive director of the International Students Community, a student group comprised of international students, said it’s difficult to recruit students from lesser-developed countries because undergraduate international students don’t receive financial aid coming into GW and “affording education in the United States is not easy.”

But GW may not want to give extra assistance to these individuals because international students are a large revenue driver, Joshi said.

Officials have relied on international students – who pay top-dollar to attend GW – as a steady revenue stream over the last several years, especially because GW relies on tuition to fund about 75 percent of its operating budget.

In 2016, international graduate students came from 127 different countries, while undergraduates represented 86. The same year, about 68 percent of the international student pool consisted of graduate students, according to institutional data.

“It really depends on the kind of institution GW wants to portray itself as to international students,” Joshi said. “Currently, all the international students – at least the undergrads who come – are people who can afford this education.”

Student Association President Peak Sen Chua, an international student from Malaysia – a country that sent six students to GW in 2016 – said students from different countries bring unique perspectives to the classroom and provide a global view on issues that domestic students may not otherwise hear.

Chua ran an SA campaign this spring focused on creating a stronger international student community through mentorship programs and connecting students from the same countries or regions, projects he said are still in the works. Even though much of the international student population comes from a select few countries, he said that doesn’t mean they all bring the same perspectives to college.

“If an international student was from China and they were from Shanghai, their experiences would be entirely different than an international student from Fujian or Beijing,” he said. “That kind of diversity – wherever it exists – still strengthens our community.”

Faculty and experts said students could benefit from exposure to a wider variety of cultures and the diversity that those students bring to campus.

Pradeep Rau, a professor of marketing, said attracting more international students from different countries could give students a better understanding of other cultures outside of the U.S. and the New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania area, which is already heavily represented.

But Rau said officials may have trouble recruiting students outside of more populous countries because those students often need scholarships and financial aid to afford the high tuition. He said students from China or countries with a larger population and strong economy can often afford to pay more than students from less economically prosperous countries.

“The big problem then is where do you get the students from?” Rau said. “GW is not an inexpensive school, so if you want to get students from different countries you have to find a way to pay for it.”

Officials have focused international recruitment heavily on China and South Korea in recent years, sending top officials on recruitment trips to meet with business leaders and government officials. The number of Chinese students at GW quadrupled between 2008 and 2013. Last year, GW established an institute for Korean Studies to expand longstanding ties to that country.

Rahul Choudaha, the executive vice president of global engagement and research at StudyPortals, an online search platform for international students, said there is “no one big block of international students” because these students vary not only by country of origin, but also by majors and socioeconomic background.

Choudaha added that universities can recruit more diverse student populations either through in-person recruitment – traveling to other countries – or through an increased presence on social media.

“In the last few years, with the expansion of online media and the cell phone technology, and the students themselves – who are now so much more comfortable in leveraging technology to make their choices – are gravitating more towards digital ways of finding their choices,” he said.

Sarah Roach and Dani Grace contributed reporting.

This post was updated to reflect the following correction:

The Hatchet incorrectly reported that Pradeep Rau was still the interim chair of the marketing department. He ended his term as interim chair in June. We regret this error.