Source: GW 990 Forms

Emily Recko | Hatchet Designer

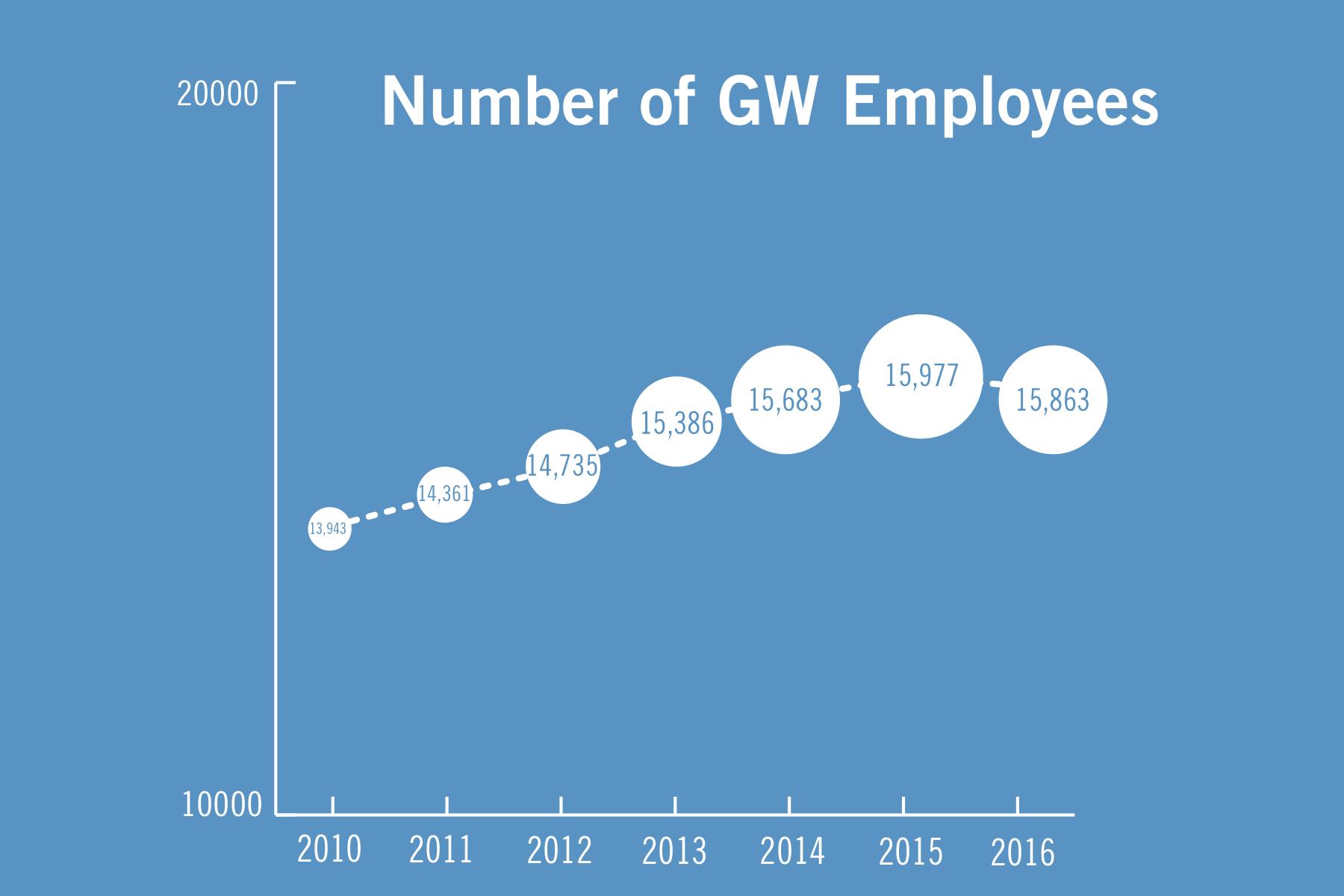

The number of employees at the University dipped in fiscal year 2016, following at least six consecutive years of staff increases.

The total number of GW employees fell by about 0.65 percent from 15,977 in fiscal year 2015 to 15,873 in fiscal year 2016 as the University entered a period of sustained budget cuts to administrative offices, according to tax documents. Experts said the decrease may stem from officials cutting or not replacing staff, but that trimming the University’s workforce may be a financially prudent move.

Officials announced at a Board of Trustees meeting Friday that the University’s revenue in fiscal year 2017, which ended in June, swelled more than its expenses, a financial result trustees said was encouraging.

GW’s revenue increased by 16 percent from fiscal year 2016 while expenses increased by 2 percent, according to an outside audit of finances.

Spending on employee salaries also ticked down in fiscal year 2016 by roughly $2.5 million or 0.38 percent, according to tax documents.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said the number of employees included on the University’s 990 tax form includes anyone who fills out a W2 income, meaning full-time, part-time or contracted faculty and staff, student employees, temporary employees, contract workers and graduate teaching and research assistants.

“The number of W2 tax forms the University issues to any individual for work performed on behalf of the University varies from year to year,” she said.

But since fiscal year 2010, the number of staff at the University had increased every year until fiscal year 2016, an increase from 13,943 to 15,977. Over that six-year span, total spending on salaries swelled from $531,602,631 to $667,797,888, according to tax documents.

Csellar said the staff reductions were not related to budget cuts that caused officials to eliminate 40 jobs in May 2016.

Former University President Steven Knapp announced a plan in December 2015 to cut budgets in all central administrative units by 3 to 5 percent each year for five years. In the previous year, spending for nearly all administrative offices was slashed after graduate enrollment levels missed projections.

Csellar declined to say which departments had decreased staff and which types of positions were cut. She also declined to say what the University is doing to mitigate the loss of employees in affected departments.

In recent years, smaller programs like music and creative writing have seen drastic cuts, administrative offices like parent services have been dissolved into larger units and officials have slowed the growth of tenure-track professors.

The University’s debt surpassed it’s endowment last fall, and efforts like a $13 million payment by September have been made to pay off the debt. To grow the endowment – and stave off future cuts – officials have relied on donors as part of the $1 billion fundraising campaign and revenue from real estate developments like The Avenue and eventually, the planned development at 2100 Pennsylvania Ave.

Nelson Carbonell, the chairman of the Board of Trustees, said budget cuts and the University’s use of alternate revenue streams led to a relatively strong financial performance last fiscal year.

“We’ve been slowly – through that planning cycle – making adjustments to the budget, managing our expenses, looking at revenue opportunities that maybe haven’t in the past been available,” he said.

In fiscal year 2017, the University’s revenue was $1,427,561,000 and expenses were $1,276,898,000, a 16 percent and 2 percent increase, respectively, from the previous year, according to recently released financial departments.

Gabriel Serna, a professor of higher education at Virginia Tech University, said student affairs positions are often the first ones cut at universities, which can mean students lose out on the support they need. Staff morale is also affected when they think their jobs are in danger, he said.

“It really affects them when you tell someone that they could be losing their job,” he said.

At GW, student affairs was hit particularly hard by layoffs in 2016. The director of academic integrity and the senior associate dean of students positions were laid off and a new division – the Office of Student Support and Family Engagement – now oversees various student support offices.

He said there are other alternatives for universities trying to increase their cash flow, primarily bringing in sponsored grants and increasing fees and tuition, which GW officials have sought to limit in recent years.

In recent years, campuses across the country have turned to cutting administrative staff after decades of expanding non-academic positions. A 2014 report by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting found that the number of non-academic and professional staff at U.S. universities had more than doubled in 25 years.

Joe Templeton, a chemistry professor at the University of North Carolina, said more than half of expenses are spent on salaries at most universities.

“If you’re going to save significant money it means that you have to have vacant positions,” he said. “To the extent that salaries dominate university finances, that’s where you have to go to find significant savings.”

Templeton said when UNC had to trim administrative positions, he found areas in which staff that could be replaced by technology or offices were unneeded layers of administrative staff between low-level and high-level positions hampered efficiency.

“It forces you to think about priorities and make some hard decisions,” he said.

Ryan Meneses contributed to reporting.