Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Eidtor

Source: National Center for Education Statistics

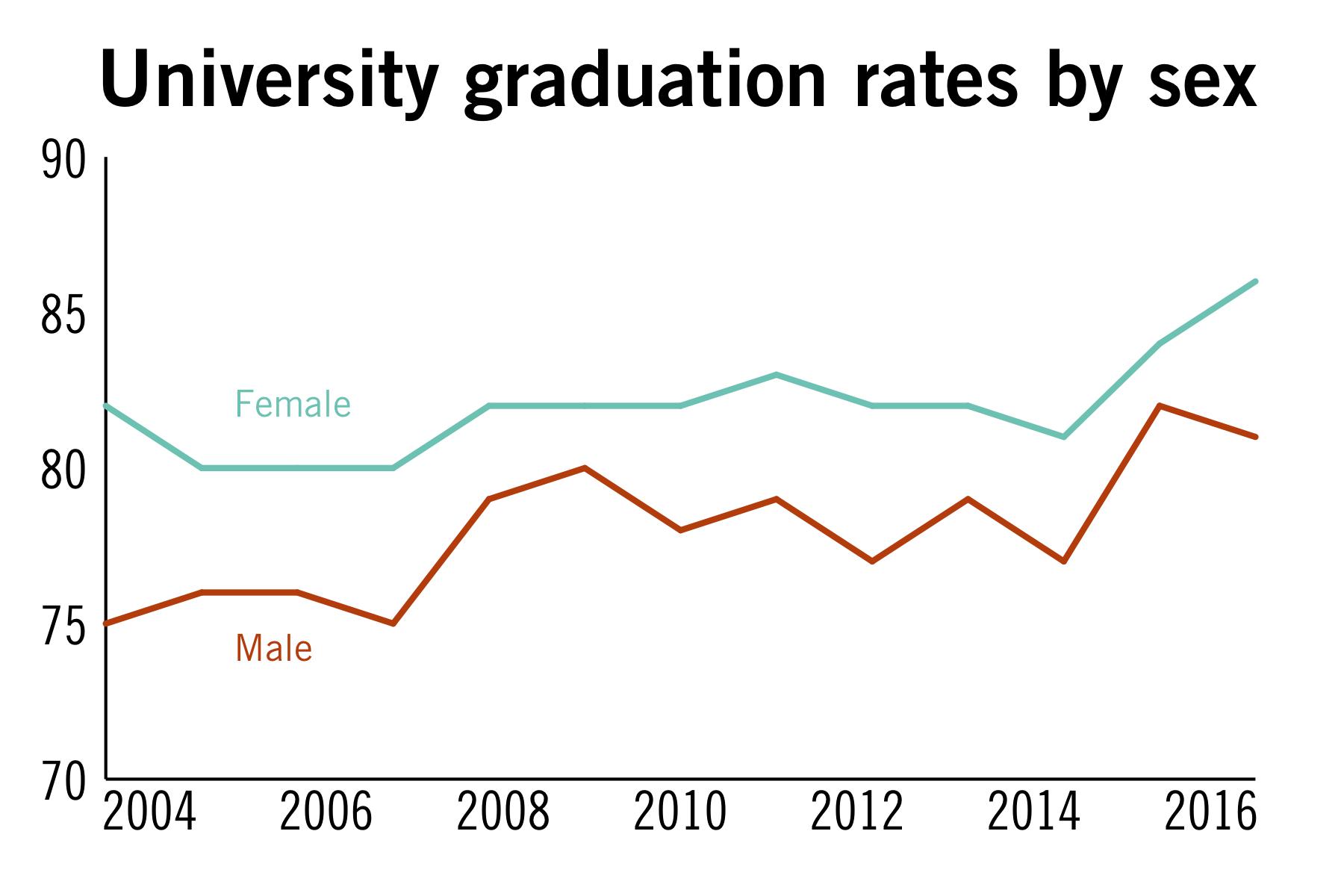

GW is graduating men at a lesser rate than women – and it has been since at least 2004.

Last year, GW’s six-year graduation rate for female students was 86 percent but was 81 percent for male students, one of the highest gaps among the sexes in recent years, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics. Lower retention rates for first generation, low-income and underrepresented minority groups have been well documented, but experts said the discrepancy between men and women is also present at nearly all U.S. universities and could be attributed to how men and women often have different educational priorities.

The trend extended to all but one of GW’s 14 peer institutions in 2016, with as high as a six-point gap between male and female students at the University of Miami, according to federal statistics. American University graduated men and women at equal rates last year.

Oliver Street, the executive director of enrollment retention, said that while “there are a variety of historical and structural factors that contribute” to differences in graduation rates among the sexes, races or income groups, personal experiences often most directly affect a student’s decision to stay in school.

He declined to say which factors specifically contribute to graduation discrepancies between men and women.

“This is why we at GW are paying close attention to ascertaining what can be done from an institutional perspective to help increase the experiences that contribute to student success and decrease the experiences that hinder progress,” he said in an email.

Street was hired last year as the first to serve in his position after officials prioritized improving retention and graduation rates. Earlier that year, the enrollment office hired a specialist to focus on retention efforts.

“Understanding student voices is an important aspect of determining what some of those institutional barriers may be so that they can be removed,” Street said.

In 2015, the gap between men and women fell to 2 percent – the smallest in recent years – with six-year graduation rates at 82 percent for men and 84 percent for women, according to NCES. At its highest, there was a seven-point gap between the graduation rates of men and women in 2004.

Diane Jones, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute with expertise in higher education, said although there is no definitive reason why men graduate at lesser rates than women, part of it could be attributed to differing educational priorities between men and women.

“What you really do see, especially at more selective institutions, is that the women seem to be far more focused on their grades and on their class ranking,” she said.

Jones said female students often recognize that they may encounter inherent disadvantages in the job market because of their sex and seek to do well in school as a result.

“Do women still have this clear understanding that I’ve got to be the best of the best if I’m going to be able to compete in my world?” Jones said.

She said the gap could also be attributed to women gravitating toward “less academically rigorous” majors and fields of study, like education or the arts.

But Paul Marthers, the vice provost for enrollment management at Emory University, said the difference is likely more attributable to personality traits. He previously worked at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, where women comprised just 32 percent of the student body, and he said they still graduated at higher rates than men despite being in a technical field.

“You see more examples of women who are willing to say, ‘I need help, and I’m going willing to reach out to that helper,’” he said. “There is more of that lone wolf mentality in boys, who will be like, ‘oh, I’ve got it, I can do it,’ and they’re in trouble, they’re sinking and they’re not as willing to say they’re in trouble and are not willing to accept and do what they need to do.”

Marthers said the graduation gap is something schools can address not only on a case-by-case basis but also in their admissions and retention practices. He said some universities are willing to “take more risks” on male candidates than female candidates at a time when more women are applying to higher education but colleges still aim to have an evenly-split gender breakdown in an incoming class.

“I think people need to just recognize that there are gender differences, just as we know there are differences whether you’re first generation, whether you’re low income, whether you come from different ethnic backgrounds, as to how you might approach college and the kind of support structure you might have,” he said.

Andrew Hanson, a senior research analyst at Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, said the graduation rate gap is representative of a larger trend of women surpassing men in educational achievements in recent years, like enrollment and attaining degrees.

He said men often still have job opportunities outside of college if they choose not to finish their education, while women, in many cases, must obtain a degree to do well in a career.

“They have a lot more access to opportunities outside of college or outside of high school, just with a high school diploma if they decide not to enroll in college,” he said. “There are still some opportunities out there for about a third of men and whereas women, in the kinds of occupations that they tend to enter into, their opportunities with just a high school education are very limited.”

Dani Grace, Monica Mercuri and Callie Schiffman contributed reporting.