University President Steven Knapp will be handing over the presidency to Thomas LeBlanc this summer, and with it his legacy of expanding and creating sustainability programs at GW.

Students say Knapp and his wife, Diane, who previously worked as a nutritionist, led a University-wide shift toward renewable energy and environmental education. Students and administrators said Knapp laid the groundwork for future environmental efforts by prioritizing sustainability projects in the University’s academics, construction work and energy consumption.

Knapp, who owns a sheep farm in Maryland, said he has always been personally interested in the subject but his sustainability policies and programs on campus came from conversations with students and growing fear over the consequences of climate change.

“I mean, it’s really frightening for a percentage of the world’s population that lives in coastal areas which are going to be threatened by this,” Knapp said in an interview earlier this month. “There are probably actual countries that are going to disappear as the waters rise.”

Since Knapp’s arrival at GW, officials have added and renovated 11 LEED-certified buildings, including the Milken Institute of Public Health. The buildings comply with specific sustainability requirements for construction, building design and energy usage.

In spring of 2012, Knapp signed a city-wide sustainability pledge, with nine other schools in the D.C. area, promising to establish goals on energy, water usage, transportation and green education.

Knapp signed in the Real Food Challenge in 2014, pledging to have one-fifth of on-campus food offerings come from local and sustainable sources by 2020.

The University set a goal in summer 2014 to derive more than half of its energy from solar panels, partnering with American University and GW Hospital to use solar-powered electricity from the Capital Partners Solar farm. Officials have added solar panels on top of four buildings, including The Dakota and Shenkman Hall.

Kathleen Merrigan, the executive director of GW’s sustainability collaborative, said Knapp has been a leading force in environmental efforts on campus and has expanded research, education and public engagement on the issue.

Knapp launched the Sustainability Collaborative, pairing 11 different existing research programs to work on grant proposals and sustainability research across disciplines.

“It’s something that you build relationships that allow for more interdisciplinary research, which is part of our plan,” Merrigan said.

The University started the sustainability minor in 2012 that has since become the second most popular minor program on campus behind only economics.

She said other universities, like Massachusetts Institute of Technology, have turned to Knapp for advice on how to approach sustainability projects. GW has set the sustainability standard for urban universities, Merrigan said.

“He said ‘that’s not enough, we need to become a powerhouse in research and education and public engagement because our planet demands it,’” she said.

When Knapp came to GW in 2007, the University was given a failing “D+” rating by the Sustainable Endowment Institute. A year later, GW was rated in the bottom five for university sustainability by the Sierra Club.

GW peaked in 2011 when it climbed 27 spots in one year reaching No. 30 in the rankings. Last year, it was ranked No. 32 in the nation for sustainability.

Frank Fritz, the president of Fossil Free GW, said Knapp shifted the culture of sustainability at GW.

“I am not someone who would hold back with my criticism of the University if I had any, but he really did make it a priority,” he said.

In 2007, Knapp created a sustainability task force that eventually became the Office of Sustainability in 2009. The office has since been working to achieve carbon neutrality by 2040.

But climate activists have been frustrated with the University’s response to a student referendum calling on officials to divest from fossil fuel companies.

In 2015, more than 70 percent of voters in the Student Association election backed a Fossil Free GW-led divestment campaign. The University declined to divest, leading to protests of the administration throughout this academic year.

Fritz said Knapp could have done more to support the campaign, but he didn’t have much control over the situation because the Board of Trustees makes investment decisions.

“He has been receptive to talking to us in a serious manner about what we could do to make our investments more climate sensitive,” Fritz said.

Officials and students also credited Diane Knapp with helping the University’s sustainability efforts, especially dealing with food.

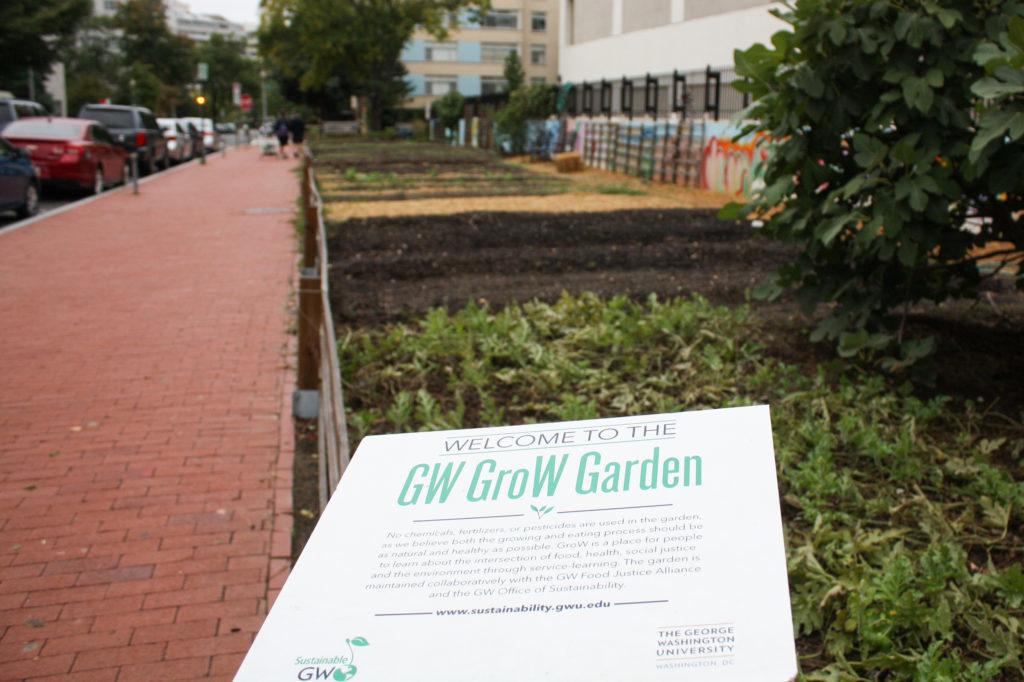

Diane Knapp leads the Urban Food Task Force, created in 2011, to give students a platform to discuss food sustainability.

“It has led to initiatives like The Store, which addresses the problem of food insecurity among our students,” she said.

She added that a lot more work needs to be done to reach GW’s goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2040 and hopes that LeBlanc continues the program.

“I hope the efforts we have made over the past decade will continue because I think we can and do set a great example as a University right in the heart of Washington, and I know sustainability matters to our students,” she said.