Siri Nadler | Hatchet Designer

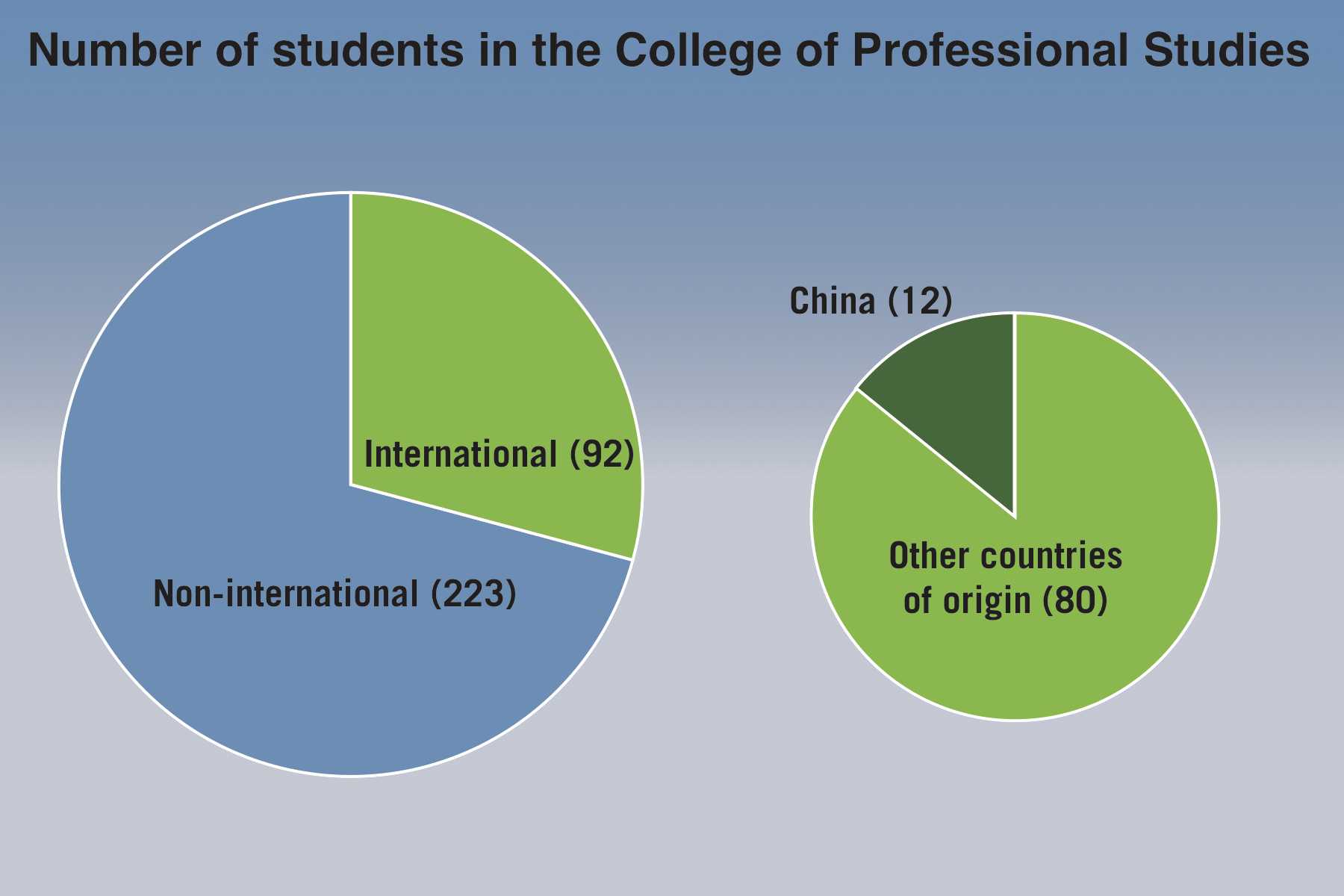

Source: Office of Institutional Research

The College of Professional Studies has struggled to recruit international students because some of the degrees the school offers are unknown outside the U.S., the school’s dean said earlier this month.

Ali Eskandarian, the dean of the school, said at a Faculty Senate meeting earlier this month that the Chinese government didn’t recognize degrees from some programs because the school offers bachelor’s and master’s degrees in professional studies – a degree much less common internationally than those in arts or sciences. Experts said this was a potential issue because it could deter international students from enrolling in the college’s programs as it seeks to expand its global footprint.

Eskandarian said at the meeting that a Chinese university nearly halted sending students to the college because the professional degrees the program offers are not viewed as equivalent to ones available in China.

“This has led to confusion in recruitment of eligible students, especially in programs for which a more common designation of BS, BA, MA or MS is normally available in other institutions,” Eskandarian said in an email.

He said “some years ago” the school was trying to bring a group of Chinese students to a few of the school’s off-campus programs, but the deal fell apart because the Ministry of Education in China didn’t know what a professional studies degree was.

Eskandarian said at the meeting that he hoped the University would try to work with the college to overcome this challenge.

“I’m hoping that the University will pay more attention to the limitations that have been imposed on us as a college so we can perform better for you,” he said.

Eskandarian declined to say what the school was doing to reduce confusion about professional studies degrees among international students.

There are currently 92 international students in the school, including 12 from China – the largest number from the country in recent years, according to the University’s institutional statistics. Eight years ago, the school enrolled about 25 international students.

Administrators set a University-wide goal in 2013 to bring in 15 percent of undergraduate students and 30 percent of graduate students from outside the United States by 2022. Officials and experts have said that expanding the University’s global presence will help GW financially since most international students pay full tuition.

Mark Reeves, a professor of physics and the director of the school’s molecular biotechnology program, said in an email that international students are sometimes concerned about receiving a master’s of professional studies because employers in their home country aren’t familiar with those types of degrees.

Reeves said GW needs to find ways to accommodate international students because of the unique perspective they bring to the University.

“International students bring diversity of culture and focus to our campus and that is of high value to GW,” Reeves said.

He said master’s of professional studies degrees, while largely unknown abroad, are valuable because they boost the skills students already have.

“They do teach students how to take their bachelor of arts or science into a job-marketable degree,” Reeves said.

Rahul Choudaha, a principal researcher and CEO of DrEducation, a global higher education research and consulting firm, said word-of-mouth and an institution’s reputation significantly impact whether international students are interested in a university. International students can be deterred from enrolling if employers don’t know about their degree, he said.

“Employers are aware more of top universities but a specific credential may become a surprise element to them,” Choudaha said.