Media Credit: Elizabeth Rickert | Hatchet Designer

Source: The American Association of University Professors.

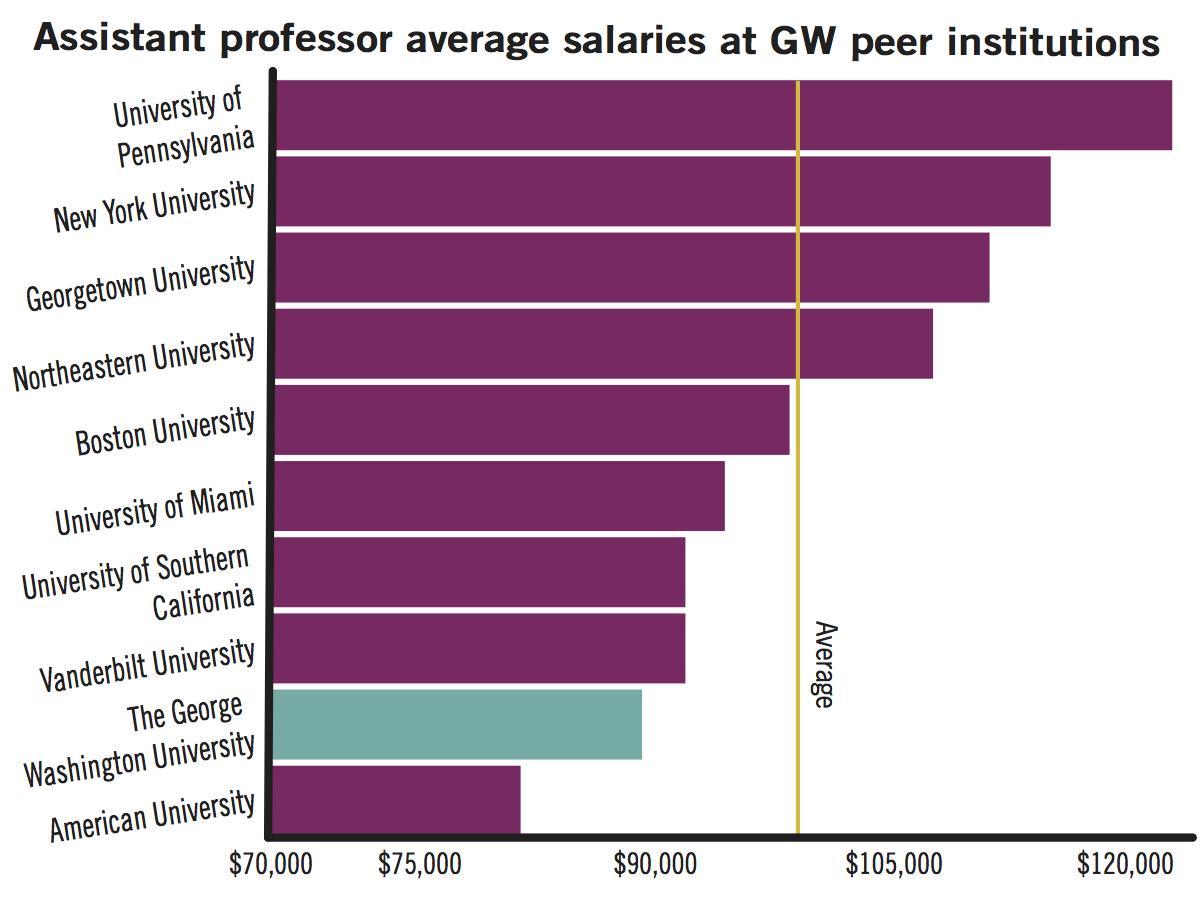

GW ranks in the bottom four of its 19 peer institutions for assistant professor compensation.

The average assistant professor salary for other market basket schools was $100,484, while GW’s was $90,821 in fiscal year 2015-2016. Faculty said the lower salaries combined with D.C.’s high cost of living make GW less attractive to current and prospective professors.

Assistant professors don’t have tenure but may be tenure-track, meaning they could earn tenure and higher compensation after a probationary period of about three to seven years. Non-tenure track assistant professors are not up for tenure, have less job security and receive lower compensation.

There are 261 assistant professors at GW.

Provost Forrest Maltzman said at a Faculty Senate meeting last month that several factors, like variation among disciplines and the market value of certain positions, contribute to average assistant professor compensation. Engineering and business professors make more than humanities professors on average, he said.

In 2013, tenure-track assistant professors in the business school earned salaries that made up 21.8 percent of GW’s total assistant professor salary compensation, compared to 16.6 percent in 2016. A smaller number of business professors could bring the average salary value down, Maltzman said.

There are 26 assistant professors in the business school, according to the school’s website, and 18 of them are tenure-track, according to University data.

“Given these complexities, we monitor American Association of University Professors benchmark data and other indices to ensure that we are able to effectively recruit and retain high quality faculty members,” Maltzman said at the meeting.

Tyler Anbinder, a professor of history and a member of the Faculty Senate’s appointments, salary and promotion policy committee, said GW should increase its compensation for assistant professors to match D.C.’s high cost of living. Compared to all other cities of the market basket schools, D.C. ranks second-highest for cost of living, behind New York City.

Assistant professors, I think have the hardest time adjusting when they move to Washington because it costs so much here and they’re earning so little.

“Assistant professors, I think have the hardest time adjusting when they move to Washington because it costs so much here and they’re earning so little,” Anbinder said. “Typically those are people at that stage where they’re having kids, they’re buying a home for the first time.”

Anbinder said the most typical way for a faculty member to receive an increase in pay is by getting an offer from another institution. This puts professors in “the wrong mindset” because they are focused on securing a good salary instead of research and teaching, he said.

Anbinder said lower salaries for assistant professors seem to have “systemic” causes and that to solve this problem, the Board of Trustees must increase faculty compensation in the next University budget.

“The University has to decide where to prioritize,” Anbinder said. “Some years it’s building a new science building, some years its building new dorms. There’s no reason this can’t be made a priority.”

The Faculty Senate passed a resolution headed by Anbinder to raise compensation, citing healthcare costs. The resolution asks administrators and the Board of Trustees to increase faculty compensation to the median of professors’ pay at GW’s peer institutions for the next academic year.

Experts said universities located in areas with high costs of living usually offer higher salaries to attract and maintain faculty.

Samuel Dunietz, a research and policy analyst with the AAUP, said institutions located in areas with a high costs of living usually pay higher salaries and that an increase in professor salaries could attract and help retain faculty at GW.

“Schools that are in high cost of living areas tend to pay better than schools that are in low cost of living areas,” Dunietz said. “I definitely think that having an attractive compensation package is used to recruit and maintain faculty.”

Gordon Mantler, an assistant professor of writing and history, said that as a postdoctoral fellow at Duke University his salary was lower than his is now at GW, but that the cost of living in the area was half of what it is in the District.

“My lower salary there went significantly further than my higher salary does here,” Mantler said in an email.

I love being a historian in Washington. The question is, how much compensation should one forfeit to live in a dynamic city like Washington, D.C.?

Mantler added that living in D.C. provides its own benefits to compensate for a lower salary, but that it is a give and take situation.

“I love being a historian in Washington,” Mantler said. “The question is, how much compensation should one forfeit to live in a dynamic city like Washington, D.C.?”