GW researchers are building sensors that will be placed on campus and along parts of Pennsylvania Avenue to track air pollution and traffic data.

A group of faculty members met in the Science and Engineering Hall last week to build environmental sensors to track air conditions in areas throughout the city. Eight sensors were installed on the roof of the engineering building last month, measuring conditions like the temperature, humidity and air pressure. A carbon dioxide sensor will be installed this week.

Officials said they want to compile public data about bus arrival times and footage from video cameras into an interactive map from the technology consulting company Avanss. There, users can look at the data from the Science and Engineering Hall sensor, along with how many bikes are available at a given Capital Bike Share station or how much gas is in a Car-2-Go vehicle parked at a certain spot near campus.

Don DuRousseau, the director of research technology services at the Capital Area Advanced Research and Education Network at GW, said the research group is looking for additional research partners who could develop applications. He said he wants a public-private partnership to help fund the technological infrastructure like the map, which he said costs “hundreds of thousands” of dollars.

Lisa Blitstein | Hatchet Photographer

DuRousseau, who is also an alumnus, said he could imagine a person with asthma using the data from the sensors to decide which day to go outside. He added that the technology could also be used for people in D.C. to track energy usage and make their decisions about water or heating consumption with real-time data.

“This is open to anyone. All they have to do is reach out,” he said. “As long as it’s utilizing the platform, we are looking at encouraging it. Getting the word out that there’s this research potential I think is a good thing.”

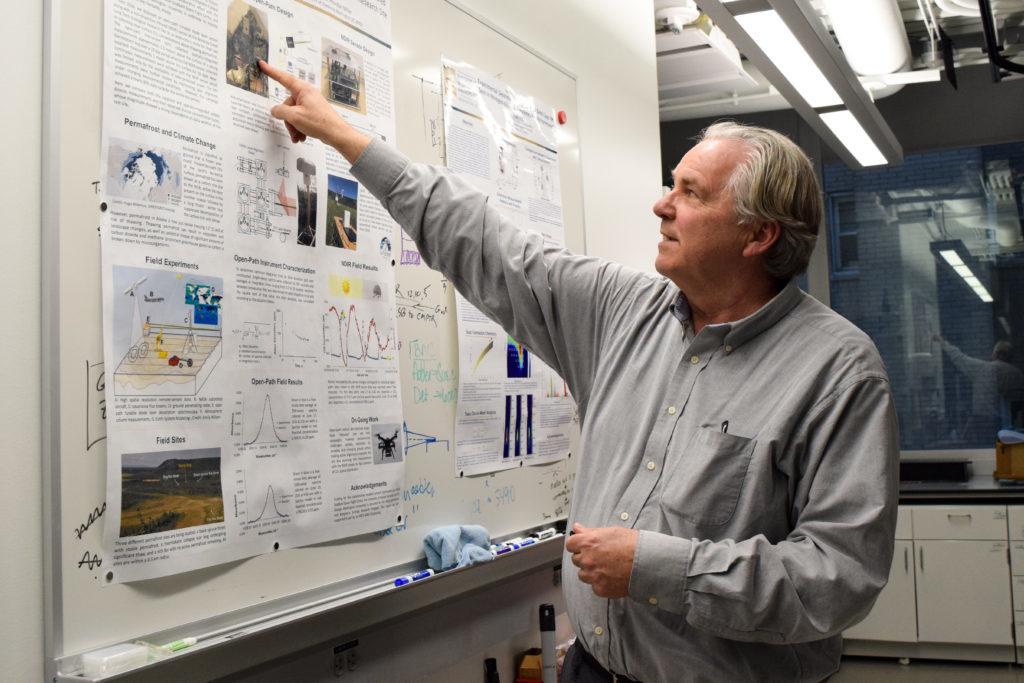

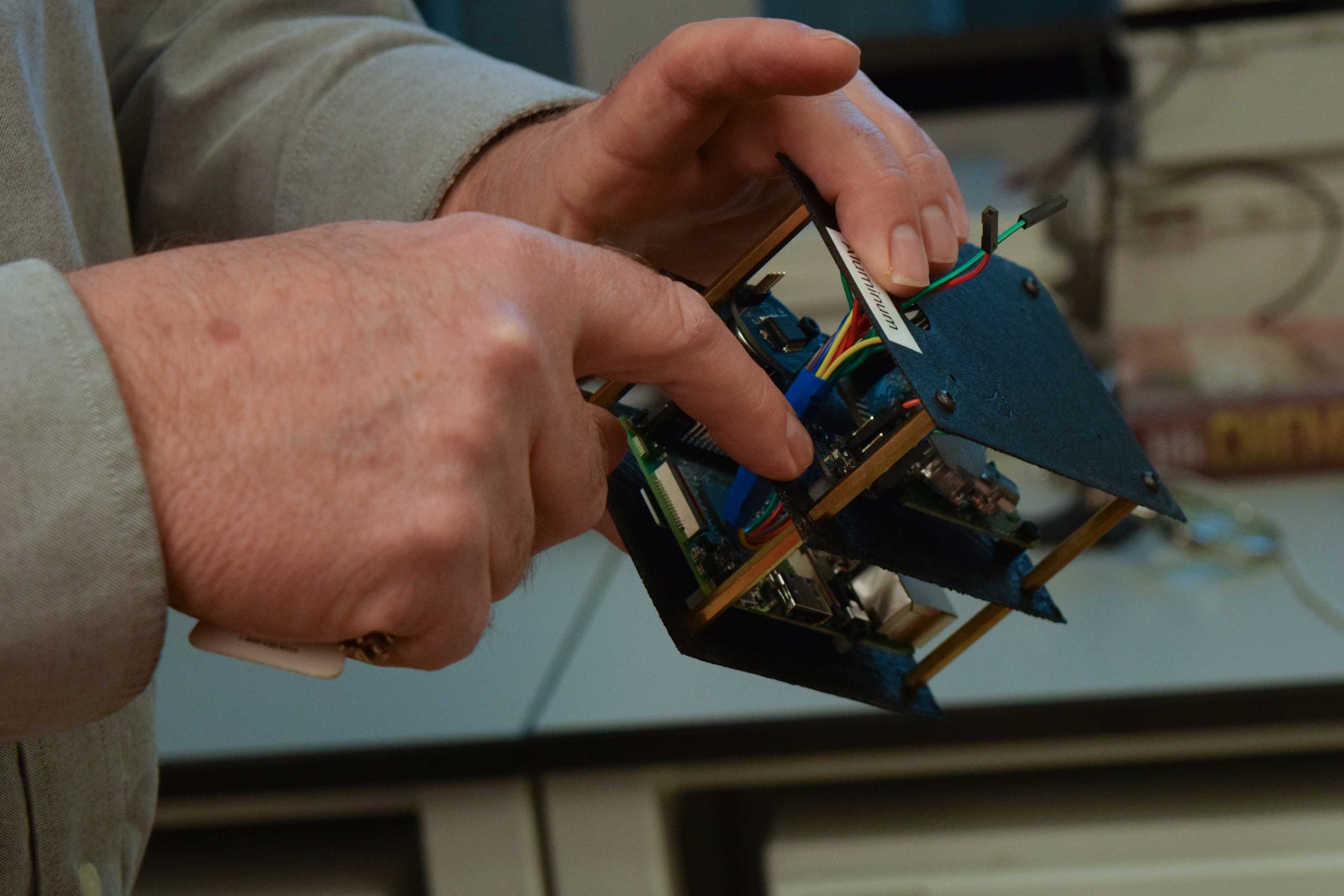

J. Houston Miller, a professor of chemistry, started building the Luftsinn carbon dioxide sensor five years ago in an honors biology class as a smaller and cheaper alternative to the sensors he uses to study carbon dioxide in permafrost layers in Alaska. Though the bigger sensors are more powerful, they cost $25,000, compared to the smaller sensors that cost about $350 each, Miller said.

Miller’s sensors will be included as part of the PA2040 program on Pennsylvania Avenue. In this project, the sensors will be built into traffic lights and will track air quality, noise and light pollution. The data will also include current traffic information, which guide emergency responders after traffic accidents.

The streetlights will have WiFi built into them to stream the data to CAAREN and will allow the information to be streamed through Ethernet, cellular or low frequency wireless methods, according to a press release.

Miller said he wants to make the designs open source so other researchers can develop their own sensors and connect them to his network.

The carbon dioxide levels from the Luftsinn sensors are currently available on a development web page, and will be updated as Miller adds more sensors, he said. He and other staff members built 11 sensors in one sitting last week, which will be tested on the roofs of GW buildings before they are put out in other areas of D.C.

“People are going to make climate science real,” he said.

D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser announced the PA2040 project in October as part of her initiative to make D.C. the first “lighthouse city” that uses technology in every aspect of the city’s infrastructure.

“With this partnership, we will provide new opportunities to increase economic development, create jobs and provide innovative education across public and private sectors,” Bowser said in the release.