Following in the footsteps of other elite universities, officials are considering funding a formal investigation into GW’s ties to slavery.

A faculty research group submitted a proposal to top University leaders last month asking for funding and a formal endorsement of their work. Faculty in the group say recognizing the research would put the University among the ranks of institutions like Georgetown and Columbia universities, where leaders have recently publicized information about historical relationships with slavery in an effort to reconcile with a dark past.

Jennifer James, an associate professor of English and the director of the Africana Studies program, penned the proposal on behalf of a 19-person committee, outlining the group’s background, rationale, research objectives and long-term goals. James sent the proposal last month to University President Steven Knapp, Provost Forrest Maltzman, Columbian College of Arts and Sciences Dean Ben Vinson and Vice Provost for Diversity, Equity and Community Engagement Caroline Laguerre-Brown.

James said receiving the president’s endorsement would show that GW takes the research seriously and would give them a consistent form of funding.

“It confers a kind of urgency and legitimacy that says, this is an initiative that is of importance to the entire University community,” she said. “It offers an opportunity for long-term stability and structure.”

We are asking that the work already underway be extended, formalized and funded under a University charge.

Faculty in The George Washington University Working Group on Slavery and Its Legacies said they hope Knapp will give the team a donation to help them continue their research. So far, they have delved into topics like the presence and labor of enslaved people at Columbian College – GW’s original name – and the college officials who owned slaves, as well as the history of racial justice activism on campus, according to the proposal.

Involved faculty say this is the first in-depth search into GW’s ties with slavery, which could reveal some of the University’s unknown connections to African American history.

“A charge coming from the highest administrative levels at the University will demonstrate not only the University’s commitment to pursuing this initiative, but serve as further evidence of the University’s seriousness in fostering an academic community responsive to its diverse students, faculty and staff,” the proposal reads. “We are asking that the work already underway be extended, formalized and funded under a University charge.”

Knapp said in an email that he has been communicating with James since receiving the proposal, and that he asked Deputy Provost Teresa Murphy to work with the group to determine next steps.

“Dr. Murphy brings to the project both her own scholarly interests as a specialist in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American history and the authority of her very senior position in the administration,” Knapp said.

Last year, Knapp’s office gave funding to University Archivist Christie Peterson to begin research about GW’s connections to slavery and hire two graduate students for the project.

“Like all members of our University community, our African American students have a legitimate interest in knowing how they are connected with the past, present and future of our nearly 200-year-old institution,” Knapp said.

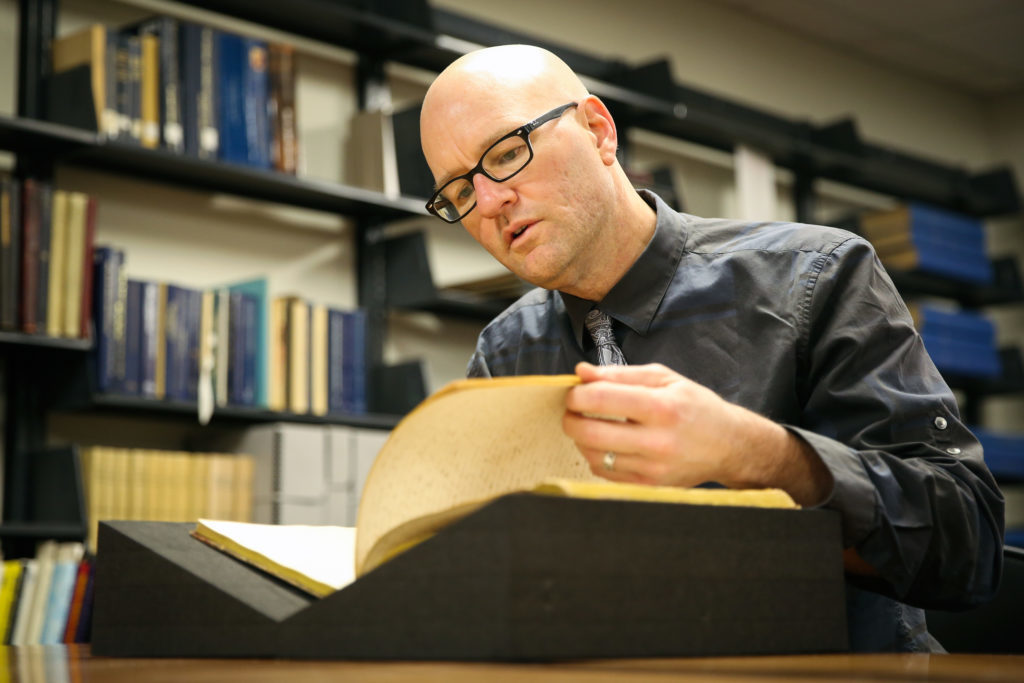

Peterson said in an email that she has been working with the graduate students since last July to search the University archives as well as items in GW’s special collections and records kept at the Library of Congress to examine the University’s history on slavery.

When I arrived at GW I found that there were some aspects of GW’s history that would benefit from further research, including questions of the university’s history regarding racial injustice.

Her team has also researched topics like the desegregation of Lisner Auditorium, the desegregation of GW’s classrooms, racial controversies under University President Cloyd Marvin and student activism around racial justice issues, she added.

“When I arrived at GW I found that there were some aspects of GW’s history that would benefit from further research, including questions of the university’s history regarding racial injustice,” Peterson said. “I think that the information we have gathered about GW’s relationship to slavery is some of the most interesting, and I think that students today will find a lot of relevance in the information we’ve gathered about the activism of GW students throughout the 20th century.”

Past lessons looking forward

The formal working group would have five committees: archives and research, local and global history, race and reconciliation, memorialization and outreach and publicity.

The proposal includes a list of outcomes that the group aspires to reach, including developing an undergraduate research course on their findings, working with administrators to install a permanent memorial and increasing engagement with black alumni.

There are few acknowledgements of GW’s racial history on campus: A bench was installed outside Lisner Auditorium in 2011 to mark the auditorium’s 1947 integration, as part of the Toni Morrison Society’s Bench by the Road Project. The project is designed to highlight significant places of black history across the country.

While a large portion of the research has examined GW’s dark history of slavery, James, the Africana studies director, said the University has other connections to be proud of. For example, Samuel Laing Williams was the first black graduate of GW Law School in 1884, and with his wife, black female activist Fannie Barrier Williams, became prominent civil rights activists.

James said the University’s 200th anniversary in 2021 is a chance for members of the community to study these origin stories as a way to understand GW’s contemporary identity.

“Universities, at their finest, are institutions committed to the pursuit and dissemination of knowledge,” James said. “They bear a particular responsibility to confront difficult historical truths wherever they are found.”

A lost history

Phillip Troutman, an assistant professor of writing and history, is a historian of U.S. slavery but said he only began looking into GW’s ties last April. He said Peterson, the University archivist, gave him documents from 1847 that revealed former trustees and officials of the then-Columbian College had owned slaves, including Joel Bacon, a president whose two slaves worked for him at the college.

Troutman said that although GW was founded in a city with a prominent slavery-ridden history, many are unaware of the University’s history. He calls it “institutional amnesia,” and said it could be a consequence of how much the University has moved and changed since its original location in the Meridian Hill area.

I’ve started to think that Foggy Bottom serves as a kind of eraser. It’s like these glassy towers just rose up out of nowhere at some unknown time.

“I’ve started to think that Foggy Bottom serves as a kind of eraser,” Troutman said. “It’s like these glassy towers just rose up out of nowhere at some unknown time. We don’t have any old buildings or old landmarks to reference, they’re gone.”

Troutman is researching the story of Henry Arnold, a Columbian College student who was forced from the college when he was caught helping Abram, a slave owned by the college steward, file a petition for freedom. Students at the time protested his abolitionist views and drove Arnold out in a riot.

“The faculty had to intervene to stop them from burning an effigy of Arnold,” Troutman said. “Here we need to come to terms not only with the institutional structures that supported slavery, but also the students, who largely determined the culture of the campus.”

Troutman said Knapp’s support would present opportunities for grants and funding to ease the financial burdens. Troutman said he has spent about $1,000 in the past year on travel costs to uncover records in Richmond, Va. and attend meetings with historians, but that these bills were covered with a CCAS microgrant.

Troutman said he is hoping to take at least two more trips in the near future that would cost more than $1,000 each.

“Having a dedicated source of funding to support this work would help it go forward more efficiently and more effectively,” he said.

‘Paying it forward’

Faculty in the working group said they want their research to have an impact outside of GW. They said they hope to join Universities Studying Slavery, a University of Virginia-based consortium of 24 institutions.

The group is a think tank and sounding board for members but doesn’t offer funding. A formalized university charge, like the one GW faculty are pursuing, is not required to join the group, but many existing group members have support from their institutions’ administrators.

If universities can contribute in powerful ways to telling the story on their campuses, promoting diversity on their campuses and sharing this with the broader public, we should all get together.

Kirt Von Daacke, co-chair of the University of Virginia President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, said the consortium likes to see a president or provost sign off on the research because it shows a top-level commitment to the faculty project.

Von Daacke said that being a part of the group can help researchers “pay it forward” and convince others to study their universities’ histories.

The group’s next meeting will be at Georgetown University at the end of next month, and Troutman said he plans to attend.

“Slavery is historically a national problem, its legacies are a national problem,” he said. “If universities can contribute in powerful ways to telling the story on their campuses, promoting diversity on their campuses and sharing this with the broader public, we should all get together.”