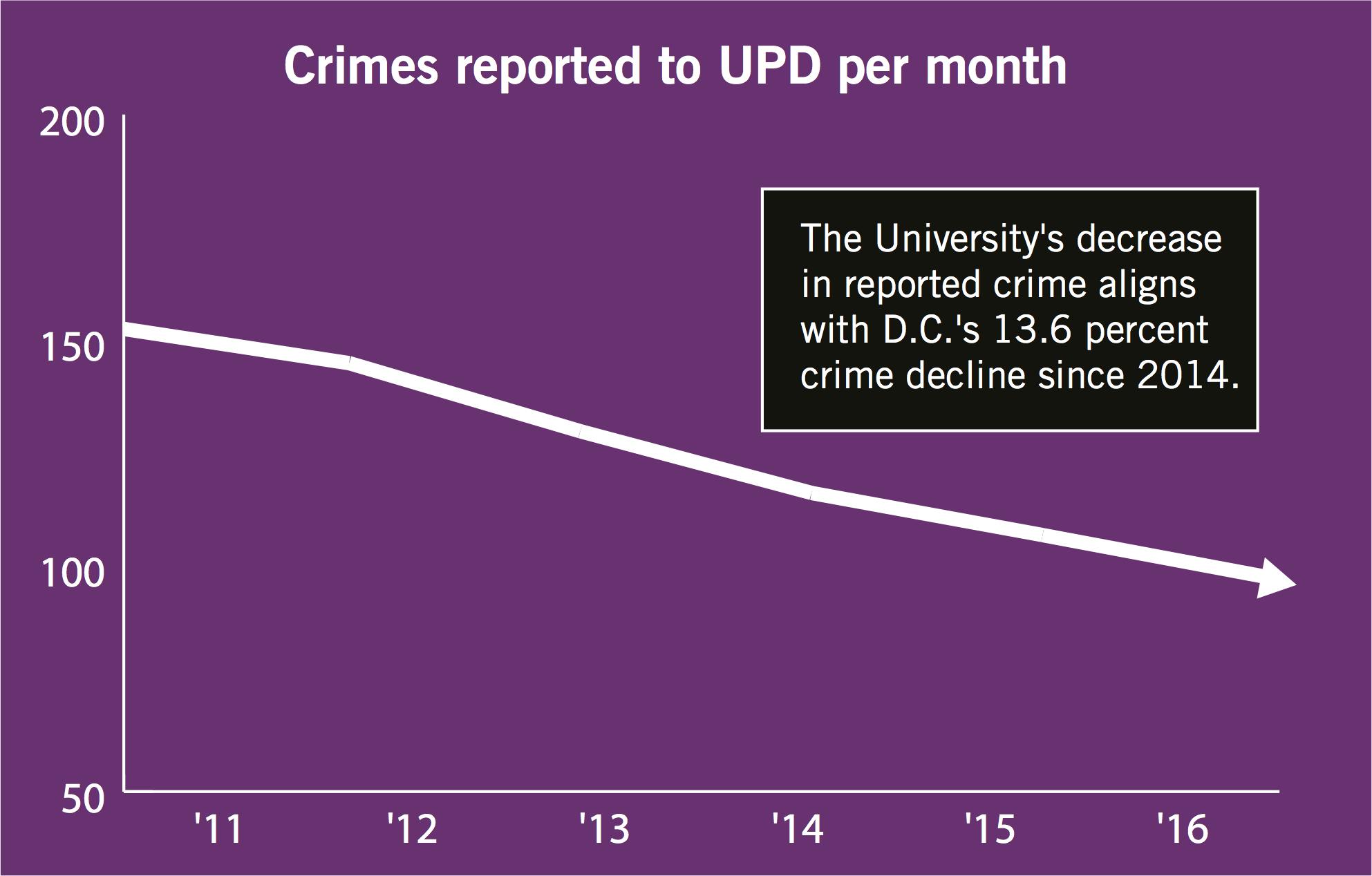

The overall crime rate on campus has decreased steadily over the past five years, according to an analysis of data collected by the University Police Department.

UPD has recorded a 36.2 percent decrease in reported crimes from 2011 to 2016. Experts say reported crime could decrease for variety of reasons, including inaccurate police records or a limited willingness for students to report crimes.

In 2011, an average of 152.5 crimes were reported per month, compared to the average of 97.25 reported each month in 2016.

During months with more than 200 reported crimes, second degree theft and liquor law violations made up 57.2 percent of the crimes. During months with fewer than 85 crimes, those two offenses made up 49.3 percent of crimes.

Graphic by Yonah Bromberg Gaber | Graphics Editor

Source: GW Crime Log

UPD Chief RaShall Brackney said adjustments made from University analysis and community outreach have helped create a safer campus environment.

“We continually review crime trends and staffing resources and readjust as necessary,” she said.

UPD recently added new outreach programs like a social media campaign and a “Coffee with a Cop” program to connect students with Brackney in person.

Brackney said more thefts occur early in the school year because people are less careful about guarding their belongings, but overall crime totals vary year to year. She declined to give specific reasons why there were fewer reported liquor law violations and thefts over the five-year span.

She also declined to say if she thinks fewer people are reporting crimes or if less crime is occurring in the area.

Some prominent thefts from the past five years include a string of laptop thefts on campus in 2015, and one man stole textbooks worth more than $1,200 from the GW bookstore last year. At Spring Fling in 2013, police reported 19 liquor law violations – three times as many compared to the prior year’s concert.

Eric Fowler, George Mason University’s Clery Act compliance coordinator who ensures that the university is in line with the federal crime reporting law, said one reason for a decrease in reported crimes could be that people are less comfortable with reporting crimes to police, which means police would not be aware of certain crimes happening in a community.

“When we get spikes in crime, it seems like a lot more people are reporting sexual assault more often,” he said.

GW leaders have said that reports of sexual assault have also increased as more survivors feel comfortable telling law enforcement officials about their experiences.

George Mason University, like GW, also had a decrease in reported crimes. Fowler said between 2015 and 2016, crime reports dropped by 7.69 percent but pointed out rural areas have less crime than urban regions. GMU is located in Fairfax, Va., a significantly smaller city compared to D.C.

Michael Polakowski, the director of the Rombach Institute on Crime, Delinquency and Corrections at the University of Arizona, said GW’s decline mirrors crime trends across the nation.

“Crime across society has been generally decreasing for the past five years, save a few cities like Chicago and Baltimore with more crime,” Polakowski said in an email. “Therefore, we should not be surprised to see similar trends on college campuses.”

Polakowski said police department reporting can be inaccurate, which triggered the start of the National Crime Victimization Survey in 1972, which collects data from members of the general population about whether or not they are victims of crimes. The survey operates as a check on police departments, but a check like this does not exist for campus police.

If there is inaccurate reporting from the University, it could violate the Clery Act – a law that requires universities that receive federal funding to report crimes to their communities.

Overall crime in D.C. has declined 13.6 percent since 2014, according to the numbers provided by the Metropolitan Police Department website.

And university crime across the country dropped 12.9 percent from 2011 to 2014, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education’s Campus Safety and Security website.

Peter Shin, a crime analyst at the Boston University Police Department, said his department tries to “do the same thing year in and year out,” when it comes to addressing crime, but theft is the most common crime. Sexual crimes may be underreported, he added.

“The numbers we see in a lot of the cases probably are not really reflective of the actual crime,” he said.