GW draws a lower percentage of its student body from low and middle income bracket households than other peer institutions and neighboring universities, according to a new study.

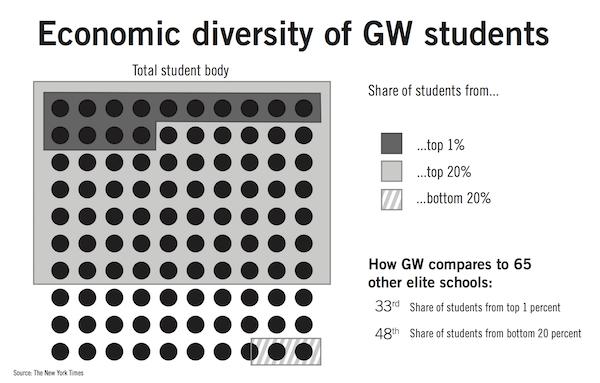

The study, conducted by the Equality of Opportunity Project and published last week in The New York Times, determined that the student bodies at high-ranking institutions are primarily made up of those from high-income families. Currently, 14 percent of GW’s students come from the top 1 percent of earning families, one of the highest shares among similar institutions.

The median parental income of students at GW is $182,000 – the 26th highest in the nation. Only 7.6 percent of the student body comes from low or middle class families.

Ross Rubenstein, a professor of educational and community policy at Georgia State University who helped develop many of Georgia’s current financial aid packages, said it is difficult to attract more students from low-income households because of the added demands on university recruitment offices in advertising to low-income students and ensuring that they have information about financial aid.

“There has to be a real commitment to providing financial aid,” Rubenstein said. “There has to be a major commitment of resources to advertise and make sure potential students know that, while the school’s sticker price is high, we will ensure that if you are accepted, we will you find a way to pay your expenses.”

GW has a need-aware admissions policy, meaning that the amount of financial aid a student needs is considered during admissions.

University officials have amped up recruiting lower income students recently. In 2014, GW reshaped recruitment plans to better promote need-based financial aid packages. And last year, the Board of Trustees earmarked more than $275 million for financial aid spending, an increase of $25 million from the previous year.

Leaders have also tried to attract more low-income and minority students, and officials cited the University’s recent switch to a test-optional application as causing the total number of applications for the Class of 2020 to increase by 28 percent. GW’s admissions office has also partnered with non-profit scholarship and grant organizations, like the Posse Foundation and Say Yes to Education, to help bring in students who otherwise might not have chosen the University and help them graduate on time.

Still, the study’s results show that GW’s share of students from the lowest income bracket remains one of the lowest in the nation, ranking 2,319 out of 2,935 colleges analyzed.

GW’s recent efforts to expand student economic diversity has yet to translate into major improvements in alumni mobility. Among lower income students, 2.2 percent move from the bottom income bracket to the top by age 34. This puts GW in the bottom 50 percent among all universities in upward mobility rate, a measure for the financial success rate of bottom bracket students.

In the category of upward economic mobility from the bottom to the top bracket, GW fares slightly better among peer institutions, ranking 15th among elite institutions and better or equal to most D.C. universities and other schools in the Atlantic 10 athletic conference.

Provost Forrest Maltzman said in an email that the mobility ranking is promising.

“The University’s 15th place ranking among 64 elite institutions on the ‘overall mobility index’ published by the New York Times is one indicator of how a GW degree can change a student’s life,” Maltzman said.

Rubenstein, the Georgia State University professor, said GW’s middling mobility performance should be encouraging, but that University leaders should be concerned that they compare unfavorably to average universities. More affordable universities hold a natural advantage in student economic diversity because of their lower tuition costs, he said.

Samuel Karlin, a predoctoral fellow at the University of California, Berkeley currently working with the Equality of Opportunity Project, said without a concerted effort to build an economically diverse student body, students from wealthy households will be less likely to shed biases about their lower income peers.

For years, GW has faced a reputation as an expensive college, after having the highest tuition in the country a decade ago and pieces featured in outlets like The Washington Post highlighting wealthy students’ attitudes.

“When we look across all colleges, we see that their levels of income segregation are quite similar to what we see across neighborhoods,” Karlin said. “This makes it a challenge for schools to foster an environment where students interact with people across different socioeconomic backgrounds.”

The purpose of the Equality of Opportunity Project’s research is not to suggest corrective methods for student economic inequality, he said, but to counter current assumptions that lower income students are not able to perform well at elite institutions.

“As a whole, poor students who attend these institutions end up with very similar outcomes to their high income peers,” Karlin said. “This should help to alleviate concern that these students could be overmatched and could lend itself to encouraging these institutions to admit more low income students.”