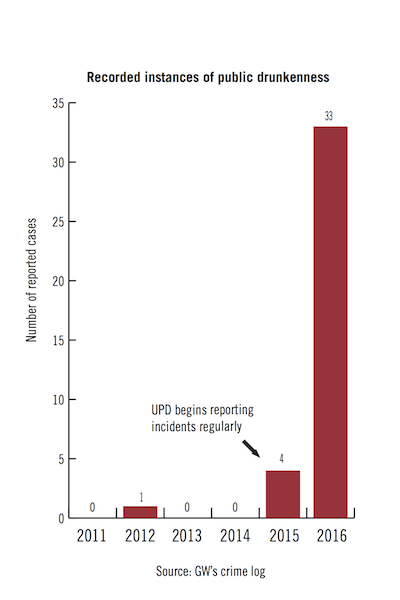

The University Police Department began regularly documenting incidents of public drunkenness last year to clarify the kinds of alcohol-related crimes that are recorded, a University spokeswoman confirmed Wednesday.

There have been 33 cases of public drunkenness so far in 2016, according to GW’s crime log. There were four instances of the crime last year, after the University began using the definition regularly in October 2015. University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said public drunkenness has appeared more in the crime log because officials wanted to give clear data on alcohol violations.

Before October 2015, one case of public drunkenness had been recorded in the crime log in October 2012.

“GWPD routinely reviews and makes enhancements to public documents such as the annual security report and the department’s crime log to provide clear and concise information to the public,” Csellar said.

The University defines public drunkenness as an incident when an intoxicated person 21 or older requires medical assistance. This differs from an alcohol violation, which applies only to individuals under the legal drinking age and does not take into account whether or not an individual drank in public, Csellar said.

Csellar added that UPD has not changed its enforcement methods for alcohol crimes and has only modified the way those crimes are classified.

UPD adjusted the crime log previously when they began organizing their records of sex crimes by separating sexual abuses and sexual assaults after the term “sexual assault” had not been used since 2011. Twenty-six cases of sexual assault have appeared in the crime log since April.

And in January, the crime log began including Title IX referrals, which were not listed previously. Eight referrals have been documented since the policy was implemented.

One UPD officer, who spoke under the condition of anonymity because officers are not allowed to speak with the media, said he has not noticed a change in how public drunkenness is handled by officers during his seven years with the department.

“I really don’t know why it’s increasing,” the officer said.

The officer said the changes in the crime log could be attributed to stricter enforcement or more intoxicated people.

Between April 1 and 3, five students were charged with public drunkenness. Three of those cases occurred in University Yard during Spring Fling.

Other D.C. schools do not regularly record incidents of public drunkenness in their crime logs.

Since 2011, Georgetown University only has one case of public intoxication. The number of alcohol violation reports has remained consistent, though, and under Georgetown’s alcohol policy, those who have alcohol in an “alcohol-free” area or an open container in public are committing a violation.

Since June, American University has documented three instances of public intoxication and 94 cases of alcohol violations in its crime log. Alcohol violations at the university include possessing alcohol at “open-air events.”

Howard University’s policy also prohibits open containers of alcohol in public spaces. Liquor law violations and public intoxication have not been recorded in the university’s crime log between 2011 and 2015.

Experts said the increase in the number of documented cases of public drunkenness at GW likely occurred because of improved enforcement and a policy shift.

Chris McGoey, the president of McGoey’s Security Consulting, said a rise in public drunkenness was most likely due to a UPD policy change.

“I bet you 50 cents that something happened. Some highly intoxicated student probably got into trouble or had a really serious health consequence because of it and maybe someone said, ‘Well heck now we gotta start keeping track of these things for liability reasons,’” McGoey said.

The University could also want to collect data on public drunkenness and where and when it is most common, he said. McGoey added that it’s common for officers on campus to let students off the hook for public intoxication to avoid adding the crime to the students’ records.

Aran Mull, the deputy chief of police at the University of Albany, said alcohol crimes are not very common on his campus but said that transportation to hospitals because of alcohol intoxication has gone up “mildly.”

When bars near campus close, it sometimes causes more intoxicated students to take their partying to the streets, Mull added.

McFadden’s, a local bar in Foggy Bottom long-considered the “campus hangout” closed down after five people were stabbed inside in December 2014, 10 months before the University began regularly recording public drunkenness.

“If you see a lot of bars where students are typically going are closing or not allowing students in or something along those lines, then sometimes that displaces it,” Mull said. “You see people out and about and being in positions where law enforcement can observe them being inappropriate.”