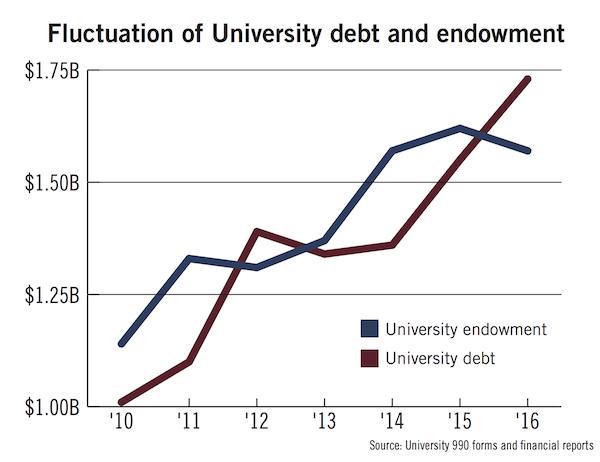

The University’s debt has surpassed its financial foundation for the first time in four fiscal years, according to recently released financial statements.

The current debt is more than $1.7 billion, about 10 percent more than the University’s $1.57 billion endowment, which decreased by about $300 million from fiscal year 2015. Experts said that as debts rise and endowments decrease in value, institutions become more reliant on tuition – a challenge that officials have been struggling to address for years.

Ann McCorvey, the deputy executive vice president and treasurer, said utilizing bonds and refinancing older debts is part of the University’s strategy to maintain low interest rates and extend the debt portfolio’s life.

“Borrowing at key times when market rates are at historic lows has helped the University make strategic investments for the long-term health and viability of GW,” McCorvey said in an email. “We will continue to monitor market conditions and our capital needs and make strategic decisions that invest in the institution and support the financial health of the university.”

Last year, the University paid off a $50 million bond taken out in 2007 but also took on another $350 million bond with a lower interest rate that should be paid off by 2045, according to the financial statements.

The University has maintained a stable credit rating that has not changed based on the new financial statements.

“GW continues to be in strong financial health with a credit rating that remains in the upper levels of several agencies’ rating systems,” McCorvey said.

Although a majority of the endowment is earmarked for things like financial aid and is not directly correlated with debt, some experts say that the relationship between the two could shine a light on the University’s overall financial health.

Donald Parsons, an economics professor who prepares a report on GW’s debt each year, said comparing the size of the debt with the endowment is not meaningful, but that rising debt can affect the operating budget and tuition reliance.

“I, in the past, have used the endowment as a comparison number to the debt, and of course the debt outruns the endowments by far, but they’re not really comparable in the sense that the endowment, a very large part of it, is in fact earmarked for special things that the donors happen to like,” Parsons said.

For the University to address its debt, officials should set aside a greater portion of revenue from tuition to pay back the nearly $2 billion owed in bonds, Parsons said. The University is about 60 percent reliant on tuition for its general operating revenue, Provost Forrest Maltzman said at last month’s Faculty Senate meeting.

“At the moment, we’re groaning under the debt and it’s having to be picked up by students in general, and that’s causing us all kinds of grief,” Parsons said. “That’s money that would otherwise be used to buy teachers and students services and the like.”

At a May Faculty Senate meeting, Vice President and Treasurer Lou Katz outlined a plan to pay off debt with revenue from GW’s real estate holdings, like The Avenue complex.

The debt mainly originates from various building projects, like the Science and Engineering Hall, which Parsons said is failing to cover the cost to build it.

Credit ratings are a more consistent way to evaluate a university’s financial health, though, experts said. GW has maintained upper-level ratings in recent years.

Jennifer Delaney, an associate professor of higher education at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, said ratings from credit agencies like Moody’s or Standard & Poor best determine an institution’s financial health. Credit rating agencies account for factors like the debt and financial foundation to determine their confidence in a school to pay off its bonds.

But if the debt were to continue to rise quicker than the University is able to pay it off, credit ratings could eventually decline, Delaney said.

“That’s the best bellwether we have for fiscal health of the institution,” Delaney said.

She said the combination of a rising debt and the fact that the endowment is designated for specific purposes could increase reliance on tuition – a dependable revenue stream.

William Jarvis, the executive director of the Commonfund Institute, said GW’s debt falls slightly higher than the average for institutions with endowments totaling more than $1 billion, which he said is about $1.16 billion.

The relative size of the endowment and the debt would not have a significant effect on bond rating agencies’ assessment of the University’s financial health, which he said is more related to the operating cash flow and other assets that could be sold or otherwise exchanged.

Building debt is a way to “move benefits from the future into the present,” Jarvis said. He added that if the University takes out bonds to build a new academic building or residence hall, the revenue that would follow could make extra debt worth it.

“The question is, what’s the relative cost of that relative to the mission value and other returns that you would get from having that asset,” Jarvis said. “It’s a more complex analysis then just saying debt is bad or that debt needs to be gotten rid of.”

Josh Weinstock contributed reporting.