A researcher in the medical school has discovered that surgically removing a throat organ can treat a chronic autoimmune disease.

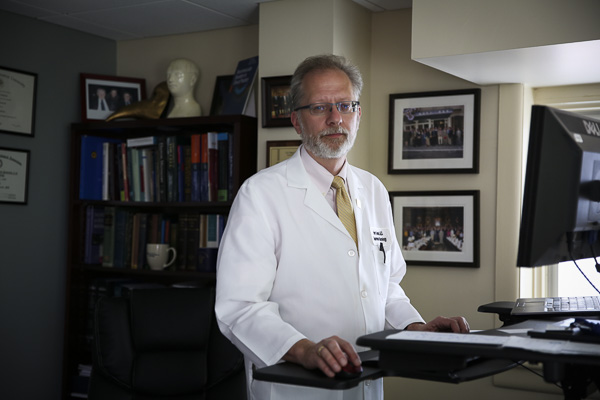

Henry Kaminski, the chair of the department of neurology in the School of Medicine and Health Sciences, worked with 100 trial investigators from Europe, Asia, Australia and North and South America to treat myasthenia gravis patients. The study, which was published in the New England Journal of Medicine last month, is the first to show clinical evidence that surgery is an effective way to treat those patients.

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease that affects more than 60,000 Americans and occurs when the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Neurologists and surgeons worked together with 126 patients at 67 centers in 18 countries to complete the study. Kaminski said each patient was randomly selected to receive the surgery, called a thymectomy, to determine if it would be effective.

“Over one hundred investigators from around the world agreed to a specific research protocol to treat patients,” Kaminski said. “The question to be answered is whether thymectomy patients was helpful.”

A thymectomy, or an operation to remove a gland in the throat, has been used for the past 70 years to treat myasthenia gravis but was controversial in its benefit to patients, Kaminski said. The study determined that the surgery reduced patients’ weakness, their need for immunosuppressive drugs and the number of times they were hospitalized, he said.

Researchers began developing the clinical trial in 2000, and they received a $5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health in 2007 to continue their work.

Kaminski said his interest in the autoimmune disease started 25 years ago when his mentor at a fellowship asked him to write a paper about how eye muscle movement relates to the disease.

“From that odd question, everything blossomed and now I have spent 25 years treating patients, doing basic research, drug development and this major clinical trial,” Kaminski said.

The researchers are now performing studies to determine which gene groups could help identify signs of the disease to tailor therapies and treatments, he said.

“We collected biological samples from patients during the course of the study,” Kaminski said. “We intend to identify markers that may predict benefit to ultimately tailor therapies better.”

GW is housing a collection of samples from the study, he said.

Gil Wolfe, the first author on the study and chair of the department of neurology at the University at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, said that electronic registries for data, email and electronic communication made organizing and communicating with researchers across the globe manageable.

This research project was a unique team effort because it involved urologists, surgeons and pathologists all working together from around the globe, Wolfe said.

“With the active involvement, recruitment and analysis lasting basically a decade, we had to have the patients stick with us, the investigators around the world stick with us and the funding agencies stick with us,” Wolfe said. “And in the end we were really able to answer a question that persisted for a half century or longer.”