Update: Sept. 7, 2016 at 12:11 p.m.

A study found that female faculty members at institutions across the country are not hired as often as males for tenured positions.

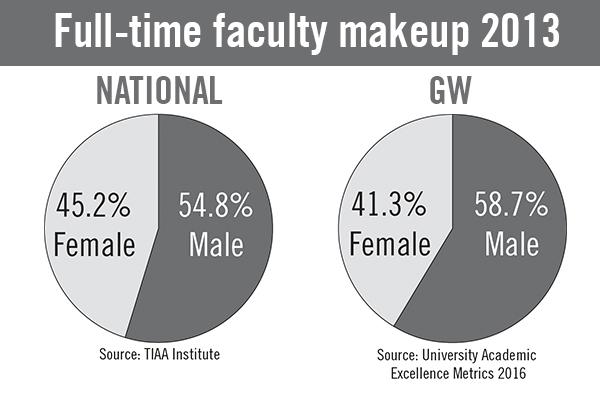

A study released by the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America Institute last month, which evaluated faculty diversity in both race and gender in higher education between 1993 and 2013, found that while faculty diversity has generally grown, diverse faculty have struggled to secure tenured or tenure-track positions at the same rate. And at GW, the total number of tenured faculty members lags behind the number of male faculty.

Female faculty at GW still fall behind their male colleagues in both non-tenure and tenure-track positions: In 2015, women made up about 42 percent of the full-time faculty, a 3 percentage point jump from 2011. In tenured or tenure-track faculty, women made up about 38 percent of the group, up from about 35 percent in 2011.

In 2013, roughly 45 percent of full-time faculty nationally were female, but women made up only about 37 percent of tenured or tenure-track faculty positions during that same year, according to the TIAA Institute.

Officials have focused on increasing the number of tenured female faculty at GW: More than 60 percent of the University’s tenure-track faculty hires in 2014 were women, former Provost Steven Lerman said at the beginning of 2015.

Provost Forrest Maltzman said in an email that hiring faculty who are both diverse and the best possible candidates is his goal for all tenure and non-tenure track positions. He added that having a diverse faculty is important because it increases the “intellectual vibrancy” on GW’s campus by exposing students and fellow faculty members to a variety of experiences.

“I expect units to hire world class faculty, and if biases preclude certain candidates from getting full consideration, we are not getting the best,” Maltzman said.

GW has instituted to encourage diverse hiring, including trainings for search committees, subsidized additional campus visits for potential hires and extra funding for some positions, Maltzman said.

He added that he looks forward to working with Caroline Laguerre-Brown, the new vice provost for diversity, equity and community engagement, who she was hired in May.

“She has built a framework for hiring diverse faculty in her prior positions and will be focusing on this effort in her new role here at GW,” Maltzman said.

GW’s diverse faculty numbers have plateaued in recent years, despite an increased effort on hiring minority faculty. Minority faculty made up about 30 percent of GW’s full-time faculty in 2015, up from 27 percent in 2013 — well above the national percentage of minority faculty found by the TIAA institute, at nearly 20 percent.

Erin Chapman, an associate professor of history, said she’s concerned about how GW hires and maintains diverse faculty members long enough to earn tenure.

She said that she has seen other female faculty members leave the University because they didn’t feel supported.

“Since joining George Washington in 2009, I have witnessed three colleagues, three friends of mine, ultimately decide that they wanted to leave GW,” Chapman said. “They decided they would rather find opportunities elsewhere than stay long enough to gain tenure. GW did not do enough for them.”

Mollie Manier, an assistant professor of biology and an Asian-American woman, said she served on her department’s most recent faculty search committee, and she viewed the experience as an opportunity to advocate for hiring another female assistant professor. Before that, she was the only female assistant professor in the department.

“It was clearly for me very important to try to hire a woman,” Manier said. “Luckily, all three of our shortlist candidates were women, so I did not have to try to fight for somebody.”

Manier said people outside the University could perceive GW as a homogeneous community — a reputation that can be harmful when recruiting prospective students and faculty.

“GW, as you are probably aware, has a reputation of being rich and white, and while my classes contain many faces of different shades, there is a different story with regard to faculty hires,” Manier said. “It is important for students to look at faculty and know that there is somebody who looks like me, somebody who can understand me.”

Recent University initiatives — like adopting a test-optional admissions policy, which officials linked to an increase in applications — have helped increase student enrollment from minority student populations.

Kimberly Griffin, an associate professor of higher education at the University of Maryland, said some faculty members may be dissuaded from pursuing tenure in a research setting like GW where they may not feel like part of the community.

“Institutions continue to struggle with figuring out what increasing diversity in the professoriate means in practice,” Griffin said. “Some professors feel like they do not have someone advocating for them personally and professionally.”

She added that students can become advocates for professors who inspire them.

“Students do have a voice, and in many ways a voice louder than faculty and administrators employed at universities,” Griffin said. “Using your voice to engage in a conversation around what is important, in terms of supporting your professors, can have a profound effect.”

This post was updated to reflect the following correction:

Due to an editing error, The Hatchet incorrectly reported that Manier was the only female professor in the biology department. She was the only female assistant professor in the department. We regret this error.