A new study suggests that wealthy universities, including GW, could support low-income students if officials spent at least 5 percent of their financial nest eggs on financial aid every year.

A report published last month by the Education Trust, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting academic achievement for low-income students and students of color, found a correlation between higher spending out of endowments and lower costs of attendance for low-income families. But experts say simply spending more of a university’s financial foundation does not guarantee more student aid money, and that institutions should focus on cutting administrative costs and focusing their fundraising efforts to support low-income students.

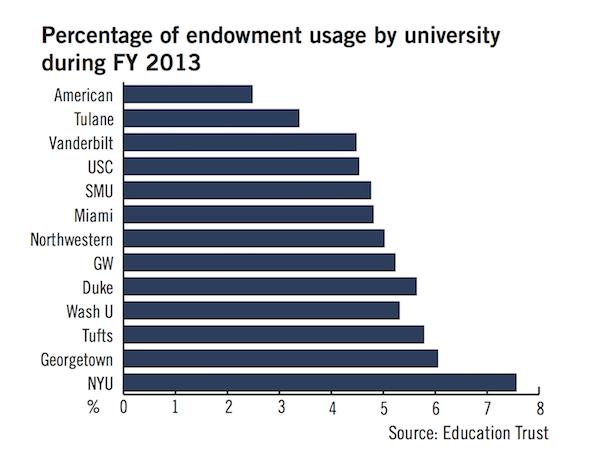

GW’s endowment is the University’s total assets, made up of donations, real estate and other holdings, which are worth more than $1.6 billion. Each year, universities spend about 2 to 7 percent of their endowments to provide financial aid, support projects and fund their operating budgets.

The Education Trust report examined the spending at 67 universities, including GW, with endowments that each totaled at least $500 million. Data was pulled from institutions’ 990 tax forms from fiscal year 2013, comparing their endowment spending to the aid they provide, particularly to low-income students who qualify for Pell Grants.

During that year, GW had an endowment of about $1.3 billion and spent about 5.2 percent of that endowment.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said in an email that GW has an “aggressive and generous” financial aid program, and that during the 2014-15 academic year, the average need-based award was $29,000. The Board of Trustees designated $275 million to fund financial aid this academic year.

“The University anticipates increasing the aid budget over the next few years,” Csellar said in an email. “We expect that the funding will come from a combination of philanthropy, including endowed funds and University spending.”

Andrew Nichols, the director of higher education research and data analytics at the Education Trust who led the study, said despite universities’ doubts in their abilities to spend more money, institutions can serve more low-income students by focusing future fundraising on financial aid.

“The point of our paper is to really push those institutional leaders who are making policy decisions to think about different ways they could possibly leverage their endowment to really support low-income students,” Nichols said.

GW officials said last month that the remainder of the University’s capital campaign, which aims to raise $1 billion by June 2018, will prioritize support for scholarships and other forms of student aid.

Sara Garcia, a higher education research analyst at the Education Trust, said GW has “room to grow” in its endowment spending for low-income students. GW’s spending rate dropped to 4.67 percent in fiscal year 2015, according to the University’s tax documents.

“If they dropped the spending rate below 5 percent, that is a problem,” Garcia said.

Universities should spend at least 5 percent of their endowments each year to support low-income students, according to the report. The report uses a 5-percent spending threshold because that is the minimum spending mandate for most nonprofit institutions. Universities are exempt from this threshold because of their societal contributions through education.

But experts say the Education Trust’s promoted spending practices could ultimately harm institutions’ finances, and that there are better solutions to aiding low-income students.

Sandy Baum, a senior fellow in the Income and Benefits Policy Center at the Urban Institute and a former professor at GW’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development, said asking universities to spend more money out of their endowments could whittle them away, endangering the nest eggs for future students.

Studies like the Education Trust’s can cause people to misunderstand endowments to function like savings accounts, not as investments that are dependent on market fluctuations, she said.

“The idea that you should not worry about what happens to the endowment and about preserving it makes no sense as a long-term plan,” Baum said.

Richard Vedder, an emeritus professor of economics at Ohio University, said low-income students would be better impacted if a university decreased spending in other areas by cutting administrative bureaucracy and slashing academic costs.

“Most universities have greatly expanded their bureaucracy in student affairs, development offices, across the board,” Vedder said. “If GW eliminated 80 or 100 of those, they would have saved $10 million. If that meant $5,000 more per low-income student, that would make a real difference.”