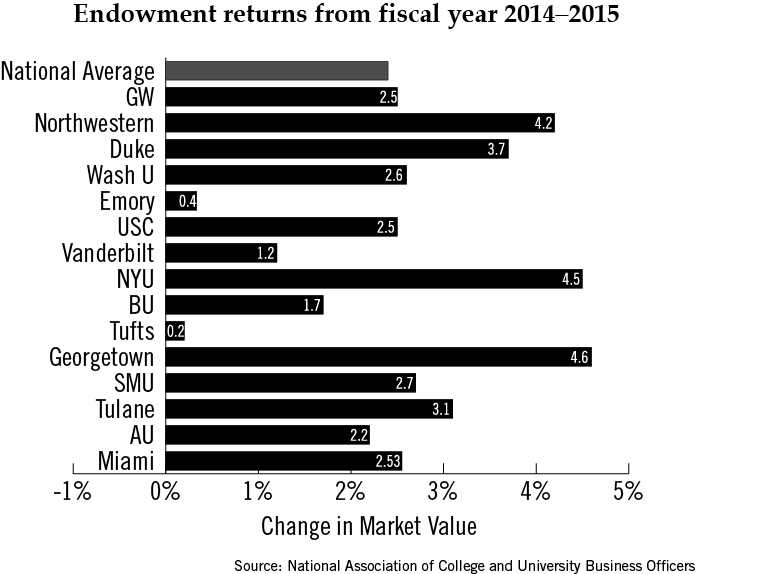

GW’s endowment grew by less than 3 percent last fiscal year, a significant drop from the previous year.

Those returns were slightly higher than the national average of 2.4 percent, the lowest return since 2012, according to new data. Experts said the sharp decline is due to a variety of global factors like a slump in oil prices and the economic downturn in China.

GW’s endowment – a financial foundation used to fund professorships, scholarships and construction projects – totals about $1.6 billion. In fiscal year 2014, it grew by 14.6 percent as healthy markets bolstered investments across the country.

The returns last fiscal year were also far lower than the 7.5 percent growth endowments need in order to “maintain their purchasing power,” according to the report. The returns were released last week in an annual survey of 812 institutions from the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

Harvard and Yale universities and the University of Texas system saw the largest returns – though all three also have the largest endowments in the country, according to data compiled by the Chronicle of Higher Education. Harvard University’s endowment is nearly $36 billion, an amount that has been buoyed by massive donations, like a $400 million donation last summer.

The majority of participants in the Nacubo study, about 80 percent, reported increasing endowment spending – despite the decline. Among the schools that increased spending, the median increase was about 8.8 percent, according to the report.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said capital markets performed poorly in fiscal year 2015 compared to the year before, which accounted for the lower returns. She said that because of GW’s long-term investment strategy, a year of lower returns will not hamper future growth.

“The endowment is invested with a long-term horizon to ensure that it will grow at a rate above inflation after spending, which it has done over the last five- and 10-year periods,” Csellar said. “We are pleased that our endowment continues to support students and faculty and provide them with a world-class learning experience,” she said.

Still, lower-than-expected returns can hurt institutions, which typically rely on endowments for about 10 percent of their operating funds, according to the Nacubo report.

“Lower returns may make it even tougher for colleges and universities to adequately fund financial aid, research, and other programs that are very reliant on endowment earnings and are vital to institutions’ missions,” Nacubo President and CEO John Walda said in the report.

GW’s endowment grew by 5 percent in fiscal year 2013, a smaller amount than those of its peer schools. Returns fell by 2.3 percent the previous fiscal year.

Georgetown, Northwestern and New York universities had the highest returns among GW’s 14 peer schools last fiscal year – about 5 percent each. Northwestern University’s $10.1 billion endowment is roughly six times the size of GW’s.

Ken Redd, director of research and policy analysis at Nacubo, said that if lower returns continued, institutions may have to lower endowment spending, “which of course would be felt by students.”

“Right now it is still too early to tell if lower returns will continue for the rest of this year or into next year,” he said.

Despite this year’s lower returns, Redd said that 78 percent of schools increased their spending for financial aid, research and other support services. He said that spending helps students and faculty feel secure, and shows that lower returns do not have an immediate effect on a university’s operating budget.

Between 2010 and 2015, GW’s endowment grew by nearly half a billion dollars. But, its size ranks No. 9 among its 14 peer schools.

About 40 percent of GW’s endowment is made up of investments in real estate – far higher than the national average of about 6 percent, Redd said. But real estate investments can be a risk because they are not easily sold off if an economy declines.

GW outsourced the management of its endowment in 2014 to the Arlington-based firm Strategic Investment Group. About 43 percent of the institutions Nacubo surveyed had also outsourced management, a percentage that did not change from the previous year.

Cristian Tiu, a professor of finance at the State University of New York at Buffalo, said real estate investments can underperform in years of low economic growth, hurting institutions that are heavily invested in that area. Still, he said one year of poor performance is not necessarily a signal of future trouble.

“I wouldn’t be worried if the returns in one particular year were low,” he said.

Avery Anapol contributed reporting.