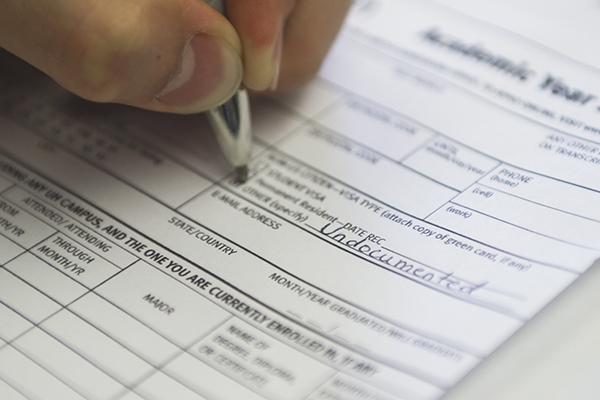

When one student, then a senior in high school, had to send the government additional paperwork to qualify for federal financial aid because her parents are undocumented, she almost didn’t make it to her top choice school: GW.

The student, who is now a junior at the University, said if it were not for a phone call from the headmaster of her private school to GW’s Office of Student Financial Assistance, she would not be on campus. Her mother, a native of the Dominican Republic, stayed in the U.S. after her visa expired, and both of her parents lack Social Security numbers.

“Because of the confusion, I wasn’t going to receive my aid by the college acceptance deadline, and I couldn’t deposit at any school because I wasn’t sure I [could go] to GW,” the junior, who is a U.S. citizen, said. “Under other circumstances, if I had gone to the public school in my zone, that wouldn’t have happened.”

Earlier this month, the Department of Education released guidelines on how institutions can support undocumented students. Though GW does not ask for proof of citizenship when students apply, its policies also do not make it clear that the University could accept and support undocumented students.

The government recommends schools make it clear they accept students who are undocumented by establishing a scholarship for them, and that colleges train staff on the unique needs of undocumented students and designate particular staff members to disseminate information about the federal Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy, which allows qualified youths to enroll in school.

Two students, a senior and a junior, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to protect their families, said they had encountered one undocumented person enrolled at GW, but said they aren’t surprised – the status is not something people typically publicize.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said because proof of citizenship is not required to submit an application or be accepted to GW, the University does not know how many undocumented students are enrolled.

“An individual’s undocumented status is not a factor that is considered during the admissions process,” she said. “However, undocumented students do not qualify for federal student aid and we provide this information and guidance when asked.”

At least three of GW’s peer schools, Emory, Tufts and New York universities, offer special financial aid to support undocumented students who cannot complete the FAFSA, which GW does not.

For many of the children of undocumented immigrants who try to go to college, early encounters with complex financial aid forms are a permanent roadblock. Like most applicants, they wade through a sea of questions to apply for financial aid, but the stakes are higher than for other low-income students. They worry if there’s a discrepancy on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid and forms submitted directly to GW, their undocumented relatives will be subject to extra scrutiny by the government.

The Department of Education estimates that 65,000 undocumented students graduate from high school annually. About half of undocumented youth in the United States have a high school diploma, just 5 to 10 percent pursue higher education and even fewer earn a college degree.

And if the children of undocumented people – and undocumented students themselves – beat the odds and arrive on campus, they likely face a financial aid office that some say is unprepared to advise students whose parents do not have Social Security numbers or cannot co-sign private loans. They also encounter weak or nonexistent support systems among their peers.

At least 18 states have provisions that allow in-state tuition rates to be allocated to undocumented students. In Alabama and South Carolina, it is illegal for undocumented students to enroll in public institutions.

A senior at GW who was undocumented in the past and whose younger brother is still undocumented, said he attends community college because he can’t receive federal financial aid.

She said the best way for GW to help students who are undocumented, or students with undocumented family members, would be to designate a scholarship for that group so that before they apply, students and their families understand their options for financing an education at the University.

“When people talk about how to help poor students, a lot of times, being undocumented and being poor aren’t things I can separate,” she said. “It’s really hard for undocumented students to have access to programs from the government like welfare.”

For students who do graduate, the Department of Education says studies “suggest that one crucial factor in their academic success has been support from family, educators and other caring adults in their lives.”

Additionally, as with all underrepresented groups on college campuses, extracurricular activities help boost retention, which GW officials said was a major focus this year.

The government suggests teachers and counselors “work collaboratively” with undocumented students’ families to “find creative ways to finance college.”

Ane Turner Johnson, an associate professor at Rowan University who studies international higher education policy, said private institutions like GW have more leeway in how they choose to address the issue of documentation. She said typically, they also have more scholarship dollars than state schools to dole out to undocumented students.

She said private institutions may be more flexible when providing stipends for work-study jobs for undocumented students. She said that instead of providing a check, officials can apply those funds to the student’s housing or another attendance cost.

“Immigration is an emotional issue in this country. Therefore, there are also more personal issues that infect the way a professional on campus may address these students, such as those related to their own biases regarding immigrants and beliefs about immigration,” Johnson said.

For the senior, she said the stress of having close relatives who are undocumented never goes away. Once, she said, at Union Station, she saw a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement bus full of people she assumed were being deported.

“No matter where you live, the fear doesn’t go away,” she said.

Andrew Goudsward contributed reporting.