A smaller percentage of the students accepted to the Class of 2018 chose to come to GW than students in the year before.

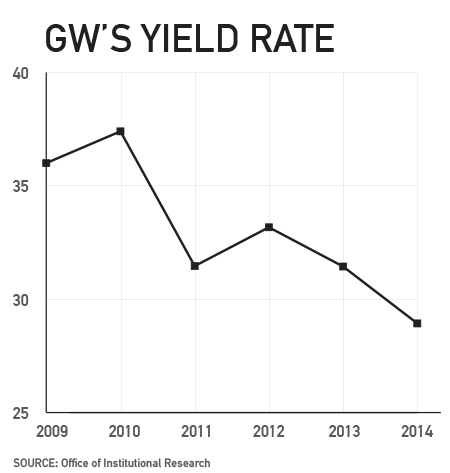

The number of students who enroll at GW after being accepted, a number known as yield rate, dropped 3 percent in 2014 compared to the year before. Officials said the decline is unsurprising because the University aimed to enroll a larger class and nationally, yield has declined as students apply to more schools and thus reject more enrollment offers.

But that figure, 28.9 percent, is 11 points lower than the average yield for universities that, like GW, accept less than half of applicants. Among those schools, yield was 40 percent in 2014, according to the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

Though a 3 percent drop may seem small, it reveals the impact early admission applications, which plummeted in 2014, have on the University’s incoming class. Last year, GW received 1,089 early admission applications, about half of the early applications the University has brought in annually over the last five years, according to GW’s Office of Institutional Research and Planning.

The University admitted 65 percent of those applicants, 21 percentage points higher more than GW’s overall admission rate in 2014.

Experts say a school’s yield rate can be impacted by factors like a school’s prestige or students’ ability to pay. And as more prospective students apply to larger lists of schools through the Common Application, officials have struggled to predict who will end up at GW.

Senior Associate Provost for Enrollment Management Laurie Koehler attributed the decline partly to the significant decrease in early applications the University received in 2014. Students who apply as early decision applicants are contractually bound to accept an offer of admission.

And the decision to use the Common Application exclusively two years ago, when Koehler was hired to merge the financial aid, admissions and registrar’s office for the first time, also accounts for the lower yield rate, she said.

Institutions rely on early applicants to predict a class size. Koehler said because fewer students applied early, the University had to admit four to five students in the regular admissions process in order to enroll one of the 2,416 students who ultimately registered to attend GW.

She said the Class of 2018’s median GPA was nearly one-tenth of a point higher than classes in the last five years, which she called a “significant increase.”

“The better we are as a University – the stronger our students, faculty and curricula are, the better the overall student experience is – the better the chance that our yield increases,” she said. “Strengthening our yield requires a University-wide effort to make GW an even greater school than it already is.”

GW’s yield rate falls in the middle of its peer institutions. More selective schools, like Georgetown, Duke and Northwestern universities, enroll about 43 percent of the applicants they accept. American, Tulane and Boston universities, which accept up to half of applicants, enroll about a quarter of the students they accept.

Experts said a decline in applications might encourage an institution to increase its acceptance rate to meet an enrollment target, and that generally private and selective schools like GW have seen an uptick in the number of applications they receive.

Jennifer Delaney, an assistant professor of higher education at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, said a school’s yield rate could indicate that its prestige has fallen, or that its admitted students who were not necessarily the best fit for the University.

“A high yield rate means that you make that offer of admission to students that are likely to attend,” she said.

Elizabeth Benedict, the author of “Don’t Sweat the Essay,” a book which aims to help those applying to college navigate the process, said the Common Application, which GW uses exclusively to sift through applications, makes it easy for students to apply to more than 10 schools.

“Colleges are absolutely overrun with applicants, so the colleges don’t know whom to say yes to anymore because they have no idea who will say yes back,” she said.

Ryan Lasker contributed reporting.