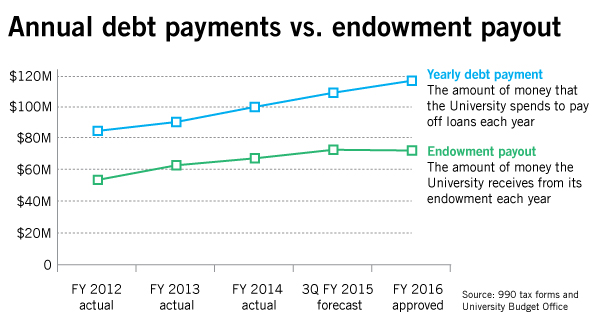

The University will pay off about $83 million of its $1.7 billion debt next fiscal year, its highest-ever payment.

That payment outpaces the money the University can use from its financial foundation by about $11 million, the second consecutive fiscal year that debt payments have been larger than the payout from GW’s $1.57 billion endowment.

Officials can spend about 5 percent of the endowment every year, using it for costs like scholarships, faculty salaries and construction. Finance experts say that while money from the University’s financial investments don’t directly go toward paying off debt, in the long term making debt payments that are larger than what can be used from the endowment could hurt GW’s overall financial health.

The University will bring in about $829 million in operating revenue next fiscal year, according to the operating budget that was approved by the Board of Trustees last month. Nearly 75 percent of that amount will come from tuition, a percentage that is higher than GW’s peer schools.

The average debt payment for a university is about 4.7 percent of its operating budget, according to a report by the National Association of College and University Business Officers. Last fiscal year, GW’s debt payment was about 9 percent of the $935 million the University had to spend for daily operations, like paying salaries.

Richard Vedder, the director of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity, said the University looks like it’s in a “precarious state” because of the $11 million difference between GW’s yearly gain from the endowment and its debt payment.

“It strikes me that GW’s financial position is more tenuous than the pace at a large moderately prestigious university,” he said.

GW’s debt load strains its ability to hire new top-notch faculty in the future, said economics professor Anthony Yezer, who is also the former chair of the Faculty Senate’s finance committee.

“That’s a fairly extraordinary kind of scheme,” he said. “To operate a university and essentially have what appears to be a large endowment and have it all committed to debt service and have another $11 million, that’s a major challenge.”

Jennifer Delaney, a higher education assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, said endowment support and debt service are often considered “separate entities” and don’t necessarily need to reconciled except to better understand a school’s financial health.

She said that the revenue from the endowment often does not pay off a university’s debt service, so though the debt might seem to overwhelm a school’s main revenue stream, a university can still use the current year’s revenue to pay the bills.

“GW is able to run a large debt service because it counts on that tuition revenue, which is current spending in a current year, not tied to the endowment payout,” Delaney said.

Nick Hillman, an assistant professor of educational leadership and policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin, said the endowment support money has two facets — restricted and unrestricted. The restricted part of the endowment is the money that can only be spent for specific reasons like “music students who play the cello,” he said.

“The endowment has historically reserved a certain amount for paying down debt,” Hillman said. “Oftentimes that money goes to debt service but it also goes to other operating expenses. It goes to a number of other places, so there’s no guarantee that 100 percent — I don’t even know what percentage of that — is covered through debt service.”