When Sassan Kimiavi went to the School of Engineering and Applied Science, he parked his car in the parking lot on the corner of H and 22nd streets.

That same block — now home to the Science and Engineering Hall — holds the Kimiavi Family Conference Room. Kimiavi, the chief executive officer and founder of luxury real estate company ALTA Development, gave a gift “in the low six figures” in exchange for the room, which is on the second floor of the complex.

“My memory of that building was getting my car ticketed and booted,” Kimiavi, a triple alumnus of the school, said. “My memories were very negative, but now they’ve turned into this beautiful, very positive building that I think is seriously going to improve things at GW.”

He said he began speaking with officials at GW after a student called him five years ago, hoping to speak with alumni about their successes. That conversation turned into a meeting with the school’s dean, David Dolling. Kimiavi said the donation was “a good way to support the school and its vision.” He and his wife, alumna Gazelle Hashemian Kimiavi, began serving on the school’s national advisory board in 2013.

Dolling declined to comment on the school’s fundraising strategy, the timing and amount of certain naming gifts, the number of individual gifts, officials’ fundraising strategy or how officials will change their marketing plans now that the building is open.

Since before construction began on the building in 2011, officials have been seeking out alumni and long-time donors, asking them to contribute to the costs of the $275 million building, and in turn get their names on offices and conference rooms. Experts say asking for a higher number of smaller gifts can be an alternative strategy if donors aren’t willing to make gifts large enough to name an entire complex.

Officials have historically struggled to raise funds for the building since donors typically prefer to give to programs or create endowed professor positions. The fundraising plan for the building changed this November, just months before its January opening, after University officials were not able to secure enough money through donations.

The hall is the University’s most expensive academic building to date, and officials had initially planned on raising at least $100 million through fundraising to cover its construction costs.

Aristide Collins, the vice president for development and alumni relations, said the office is still seeking a donor willing to pledge the right amount to name the building. He said naming opportunities within the building start at $25,000 and “reflect [donors’] personal interests.” Officials have never publicly said how much a gift to name the Science and Engineering Hall would cost.

He said the office has changed its fundraising strategy since the building opened this semester, transitioning from promoting the building’s construction to the programs housed in the hall — an area typically more appealing to donors.

“We are shifting our focus from fundraising for the building itself to how this facility will be used to advance university goals in research and discovery as described in GW’s long-term strategic plan,” Collins said. “SEH epitomizes GW’s investment in research infrastructure and facilities that enable innovative research and teaching.”

The development office has called on top officials in SEAS, the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences, the Milken Institute School of Public Health and the School of Medicine and Health Sciences “to identify potential philanthropic opportunities to support SEH and the programs within it” since 2010, Collins said.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said the University has raised nearly $50 million for the building’s “academic programs and facilities” since July 2011.

Csellar said University officials have been asking some past donors to increase the size of their gifts as part of GW’s fundraising efforts.

“Cultivation of major gift donors is done on a highly personalized basis,” she said. “When appropriate, initial donors to the facility have been asked to increase their support.”

Several donors said they were approached by University officials in the last five years to connect with SEAS by making smaller donations or joining the school’s advisory board.

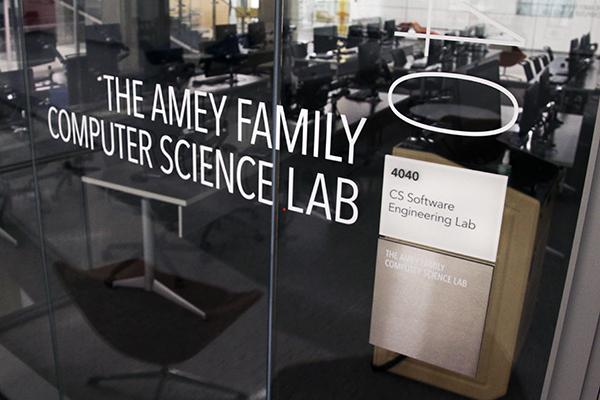

Trustee Scott Amey, who graduated in 1975 with a master’s degree in computer science, donated $1 million for the building’s construction on the condition that other donors would match his gift. His family’s name now hangs on the fourth floor of the building in front of a computer science lab.

“It’s very impressive to look in and see that room full of computers,” Amey, also a member of the school’s advisory board, said.

Amey, the owner of the government-contracted business Amyx, is a frequent giver to GW. He gave $50,000 that other donors matched for career services at SEAS in 2004 and created a scholarship fund for students whose relatives died in the military.

He said he chose to donate to help cover the building’s costs because he thinks SEAS could become the top engineering school in D.C. now that new facilities can draw in leading researchers and faculty from across the globe.

“I thought having a facility that they would build would be the key to bringing in those faculty that are not only great teachers but do innovative research,” Amey said.

Arthur Criscillis, a managing partner at the fundraising firm Alexander-Haas, said a donor could have to pay up to half of the building’s construction costs before a university would name the building in the donor’s honor.

“It provides an opportunity for donors who are interested in what the building accomplished to make a contribution and to be recognized for that contribution,” Criscillis said.

Several other buildings and schools on campus are still available for naming gifts, including the GW School of Business and the GW Law School. Duques Hall, which houses the business school, was renamed after a $5 million gift in 2002.

Cynthia Hancock, the former director of donor relations at Riley Children’s Foundation, which fundraises for Indiana University’s hospital and health facilities, said officials will start a construction project by identifying areas of the building that could appeal to donors. She said officials typically look to get donor names on building entrances, classrooms, laboratories and lecture halls.

“[University officials] look at every space within a building that could have any attractive value to a donor and assign a gift amount to that, too,” Hancock said. “You come upon people who have really visceral connections inside the space.”

Reg Mitchell, who got his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from SEAS in 1965 and 1967 respectively, made a donation a couple years ago after GW’s fundraising office ran a half-off deal for naming gifts for faculty’s offices.

Mitchell, a retired engineer for NASA, endowed a faculty office for the biomedical engineering department by donating $25,000 — half the price of what it typically costs to name an office — in what he called “five easy payments” of $5,000 each.

Mitchell said the discount pushed him to make this larger gift, but added that he’s been giving to the University for years because of how beneficial his education at GW was to jump starting his career.

He named the office after Robert Dedrick, a professor who taught Mitchell in three courses while he was at GW and was later his thesis adviser. Dedrick, who left the University to work at the National Institutes of Health during Mitchell’s master’s education, continued to work with his master’s students on their theses, which Mitchell said was “dedication beyond our degrees.”

“It would be more relevant to put his name on it,” Mitchell said.