Updated: April 28, 2015 at 3:21 p.m.

Running a university isn’t cheap, and D.C.’s economy isn’t making it any easier.

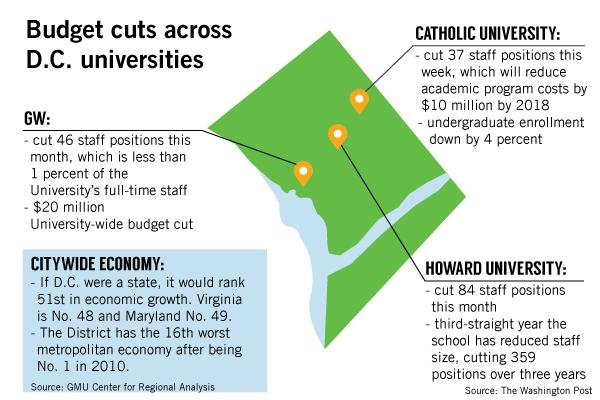

Three D.C. universities – GW, Howard and Catholic universities – have made significant staff cuts this month as part of university budget reductions. The schools’ issues are just a few examples of a difficult financial climate for universities nationwide, but experts say the District’s economy has dealt its private institutions a particularly bad hand.

Howard and Catholic universities cut 84 and 37 staff positions this month, respectively, and GW laid off 46 staffers earlier this month. Catholic and Howard universities declined to comment on what positions they cut and the causes behind their budget issues.

GW officials have asked all administrative divisions to strip about 5 percent from their budgets amid a University-wide budget crunch.

Private institutions across the country that rely on tuition for revenue are struggling to make ends meet, but D.C.’s economic downturn in recent years has magnified those effects for the region’s schools said Stephen Fuller, a professor at George Mason University’s Center for Regional Analysis.

Fuller said after the national recession in 2008 and recent budget trimming by the federal government, D.C.’s economy has suffered and students are less likely to pursue degrees in a city with a struggling economy, because it creates a more competitive job market for graduates.

“There’s less of an incentive to get your degree here, when even Detroit is outperforming the Washington metro area,” Fuller said.

D.C.’s economy is the slowest growing in the nation, just after Virginia and Maryland, and fell from the fastest growing metropolitan economy in the U.S. in 2009 to the sixteenth this year, according to George Mason’s Center for Regional Analysis. And the Washington metro area’s gross domestic product, one of the main measures used to determine the health of an economy, fell .8 percent in 2013 after holding steady for a decade, according to the D.C. Department of Commerce.

He said universities’ financial problems can be compounded by failing economies in their regions. D.C.’s economy faltered in 2012 when the federal government made $85 billion worth of cuts to federal staffers’ salaries, including cutting positions.

“We’re a company town and our company is government,” Fuller said. “We don’t have the federal dollars that were growing every year by leaps and bounds, and then all of a sudden that spigot got shut off.”

Earlier this year, the D.C. chief financial officer reported that D.C.’s population is the lowest it has been in eight years because fewer people are relocating to the city from other places in the U.S., including students pursuing degrees at D.C. area universities.

Experts said cuts at D.C. schools occur in a cycle, depending on the level of interest students have in attending certain programs. These changes have hit graduate schools hardest because those students often plan on attending classes and holding a job at the same time, and a decreased likelihood of finding that outside employment can keep students from applying to graduate schools in cities with weaker economies.

Joseph Cordes, an economics professor and the chair of the Faculty Senate’s finance committee, said universities’ graduate enrollment is dropping off nationally after increasing during the recent recession. GW officials cited a decrease in graduate enrollment for the University-wide budget crunch.

“The fact that three schools in the area happen to have problems with their cash flow shows the importance of graduate enrollment,” Cordes said. “In general, we have certainly benefitted from the fact that D.C. is destination city for younger adults.”

Lee Gardner, a finance reporter at the Chronicle of Higher Education, said schools in cities like D.C. are often considered “destination schools,” a label that can both benefit and hurt the schools. Other private universities of similar size and rank in the Midwest or Northeast regions may feel pressure to attract students to live in those areas because they are not as attractive to applicants.

“They’re trying to attract students that those areas don’t attract already, but D.C. is a population center,” Gardner said.

GW’s peer schools in other major cities are not facing similar budget issues, but have larger endowments, which may help to cover costs that GW and other D.C. universities can’t because of their reliance on tuition dollars to fund daily operations.

New York University’s endowment totals about $3.5 billion, while GW rings in at $1.57 billion. Howard and Catholic universities’ endowments are significantly smaller – $586 and $301 million, respectively. Lower ranked schools do not tend to have large endowments and rely on tuition from large enrollment numbers to finance the schools’ construction or hiring costs.

“I don’t think NYU is hurting for applicants, nor are the best schools in Boston,” Gardner said. “A lot of this is that once you get out of the top 25 or 50 institutions in the country, a lot of people are facing pressures.”

GW’s peer school Boston University has a similar endowment to GW – about $1.5 billion – but is not facing similar financial pressures.

GW fell two spots in the U.S. News & World Report rankings last year to No. 54, which experts partially attributed to the University’s relatively low endowment.

The University admitted 45 percent of students to the Class of 2019, about 3 percentage points higher than last year’s and the highest admission rate in more than a decade. A larger class, which could grow by about 150 to 200 students, could also help alleviate the University-wide budget crunch. The University also updated admitted students days this year to incentivize prospective students to attend GW.

Because private institutions with smaller endowments rely on tuition for revenue, officials search for ways to boost applications and enrollment without increasing the overall price tag, said Christian Weller, a professor of public policy at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Weller said students are less likely to spend large amounts at schools in cities with already high living expenses. Universities in metropolitan areas have higher room and board costs compared to ones in other locations and individual students can end up paying more for daily items.

“That leaves universities with the tough choice to raise tuition and fees for students or to cut spending. There is a limit to how much students will accept higher tuition in a high cost area such as D.C.,” Weller said.

This post was updated to reflect the following corrections:

The Hatchet incorrectly reported that GW, Howard University and Catholic University have cut faculty positions. GW, Howard University and Catholic University have cut staff positions. The Hatchet also incorrectly reported that GW officials had been asked to cut their budgets by 5 percent. That number only applies to administrative divisions. A graphic also incorrectly reported that the University cut 5 percent of staff positions. The University cut less than 1 percent of full-time staff positions. We regret these errors.