This is part two of a three-part series chronicling an allegedly abusive relationship between two GW students. We cover how the relationship fell apart, the healing process and the intricacies of GW’s judicial process. Part three will be published next week.

A female graduate student used up the six free University counseling sessions given to students within an academic year laying out the basic details of her four-year-long experience with dating violence.

Her situation was too complicated to unravel in fewer appointments – a level of complexity she said is common for dating violence survivors and a key reason she thinks they should be allowed an exemption to receive more free sessions. Once her sessions ran out, she had trouble figuring out the next steps to take because she had struggled to cover the cost of appointments and didn’t want to start over again with a new counselor.

“There’s a big upfront emotional investment in therapy, too. You have to explain your context and establish a relationship before any progress can be made. To have to keep retelling the story can be exhausting and discouraging,” said the student, who was granted anonymity because of the sensitivity of the situation. Her family and professors were also granted anonymity.

Now in her second year of a joint-degree program at GW, she said she was harassed, threatened and cyber-stalked by a male alumnus she met and started dating at GW in 2011, the spring of her freshman year as an undergraduate. The male alumnus was a sophomore at the time.

She said she now wants to share her story because she said GW needs to be better equipped to treat survivors of dating violence, especially in a university setting where more than 40 percent of college-aged women will experience an unhealthy romantic relationship, according to Break the Cycle, a national anti-domestic violence organization.

The barriers to healing can come after a survivor tries to protect themselves after going through the often grueling process of notifying police or campus officials about an incident. GW recorded two instances of dating violence in 2013, according its annual security report. There have been no incidents of dating violence reported to the University Police Department since last April, according to GW crime logs.

The student also said she struggled to know when to ask professionals to step in on her behalf, and she said the University did not do enough to ensure she had access to resources.

“All of this obviously happened while I was at GW – [he] was a GW student and the reporting was pretty traumatic. It was a very GW issue in my life, but yet I couldn’t get the services I needed, which was really frustrating,” she said.

While her relationship with the man began smoothly – with walks along the Georgetown waterfront, flowers and jewelry – it became unhealthy over the course of about four years. He allegedly threatened to kill her and her ex-boyfriend, and reportedly attacked her in a park off campus, according to police reports and hours of interviews.

Both students also broke two No Contact orders that GW officials put in place during their time as undergraduates. Last month, the female student secured an Order of Protection through D.C. Superior Court against the man, who is now an alumnus.

This story is the second in a three-part series giving a close look at dating violence on campus: the inner-workings of a relationship, the University Counseling Center’s response to survivors of dating violence and GW’s judicial process.

Struggling to cover the cost

GW offers six free counseling sessions to students each academic year. When the female graduate student booked her first appointment in the spring of 2012 — while she was still an undergraduate — she struggled to make more sessions fit her schedule because she often worked internships that filled business hours.

After returning from her time abroad during her second undergraduate year, she connected with a counselor at UCC who she worked with during the spring semester of 2013 and into the next fall. Because they built up a strong relationship, the graduate student wanted to continue working with the counselor after running out of free sessions.

She qualified for discounted counseling based on her family’s income and spaced out her appointments so she could keep up with paying $20 per session. Counseling normally costs $60 per session. As a student on a budget, she said she struggled to cover the costs. She also wanted to keep the appointments confidential and not ask her parents for more money.

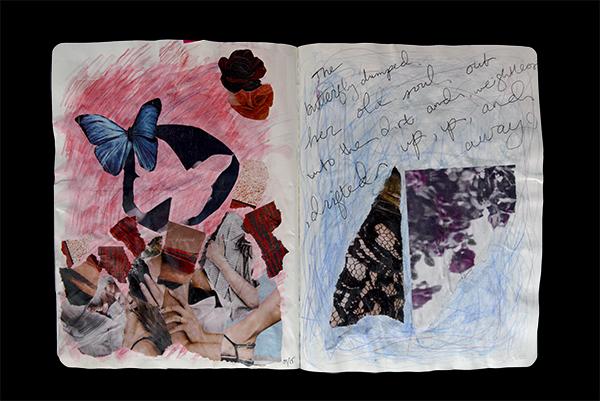

Last summer, she participated in a support group through the D.C. Rape Crisis Center, and she has turned to artwork and journaling as a way to process her emotions.

Dean of Student Affairs Peter Konwerski said in an email statement that officials “do not have plans” to change the fee structure at UCC. He said students can be referred to low-fee clinics in the area or apply for grants to cover the cost of counseling through the University’s financial aid office.

Konwerski said the Sexual Assault Response Consultative Team, a group of trained staff members who work with survivors, provides information about resources and may refer students to counseling. UCC is a short-term center where students can make initial appointments and be referred out for more long-term care.

Still, limiting the free sessions available at UCC to six is “woefully inadequate,” said Paul Schewe, the director of the Interdisciplinary Center for Research on Violence and an associate professor in the Department of Criminology, Law and Justice at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

“You’ll perhaps need a longer-term relationship of three months or six months [with your counselor],” Schewe said. “And it might be something you have to return to in another year or two as you start new relationships.”

The University has prioritized mental health resources on campus over the last several years. UCC was one of just three departments on campus to receive a budget increase last year. Officials increased the center’s budget by $200,000 between 2012 and 2013, and added five clinicians since December with specialties in areas like LGBT students, drug addiction and law students.

The center has one clinician specifically focused on relationships and trauma, according to its website.

Guiding survivors through the process

The student said administrators or University Police Department officers would list resource options for her when she would report violations, but she said she needed “someone to sit down and say, ‘This is dating violence.’”

“Even if they can’t have that conversation because of privacy or liability, at least strongly encourage me to get to UCC,” she said. “Just sending a phone number and name through email is not nearly enough, especially when it’s coming from an officer you spent 30 minutes with.”

She said GW officials need more education on the intricacies of dating violence and should create a support group for victims of dating violence. The University does not have a group counseling program specifically focused on victims of dating violence, according to its website.

Konwerski said officials choose group counseling topics based on “a variety of factors, including student need and interest and staff resources.”

“[UCC Director Silvio] Weisner’s team annually reviews the group counseling topics and will certainly discuss the possibility of adding a support group for dating violence,” Konwerski said.

Weisner declined to sit for an interview through a University spokesman.

Tina Bloom, an associate professor in the Sinclair School of Nursing at the University of Missouri who has studied partner violence, said colleges have not “quite wrapped our heads around the dynamic and difficulty of responding to survivors.”

Bloom said officials need to be aware of the resources to which they can direct a survivor, but they should do more than hand the person a list.

“You really need not only knowledge of the resources but someone that can go with her and walk her to the resource center,” Bloom said.

Building a support system

Experts said it is common for a survivor to slowly share pieces of his or her experience with close family and friends, and many may decide to never press charges or report incidents to authorities.

Her faculty mentor, who has taught the graduate student in four courses during her time at GW and speaks to her weekly, said since she arrived at GW in 2008, two other graduate students have approached her after they were sexually assaulted.

But the professor said as a faculty member, it is sometimes difficult to know exactly what students are going through because not every professor forms those close bonds. She said that’s why faculty should educate themselves about resources on campus and check in if it seems like a student needs help or guidance.

“Part of the normal process of conveying information is to help students realize they don’t have to be alone if they are going through trouble. There are people willing to be there,” the professor said.

The graduate student spent last fall semester away from campus and stayed with her oldest brother and sister-in-law, who she said have been two of her biggest supporters. During that time, she talked with her sister-in-law frequently about her experiences.

The sister-in-law said GW must better define its departments’ roles and who students should contact if they’ve experienced dating violence.

“She still cared about him, but she was scared,” the sister-in-law said. “And that scenario is probably one a lot of women in her position end up in and don’t know what to do. That’s a gray area for the school where they don’t have a lot of support.”