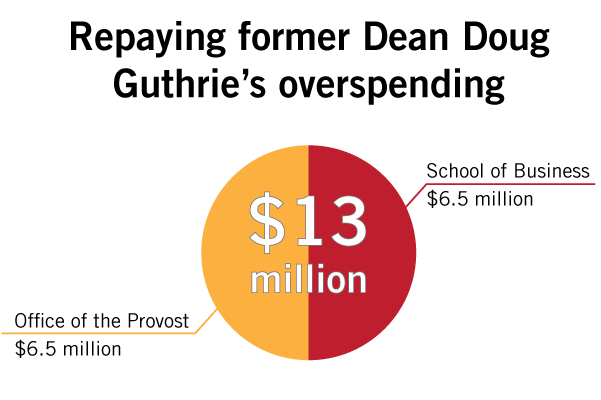

Officials have laid out an eight-year plan for the business school to pay back the roughly $13 million it owes the University – the first steps taken in two years to remedy the overspending that led to the firing of its former dean.

The school will spend six years paying back roughly $6.5 million starting in 2017, while the other half of the bill will be taken out of the provost office’s budget over six years starting in July. But now that the plan has been approved, it’s setting up a potential battle within the school for what areas will have to be cut to afford making the payments.

The school will have to weather two rounds of cuts: One next year as part of a University-wide budget crunch, and another to make up for the 2012 overspending.

When Provost Steven Lerman announced the details of the repayment plan at a faculty meeting at the end of last month, faculty members debated where cuts could be made, including areas like travel expenses, and whether to cut administrator positions, faculty who were present said. Others criticized the plan and said the University should have decided to forgive the deficit.

Lerman said it’s a “judgment call” to have University officials figure out who is responsible for making the payments on the deficit. The timeline is set for eight years to allow the school to continue functioning without placing too much of a burden on it, he added.

Schools and administrative department budgets are already being cut by about 5 percent this year after the University missed revenue projections overall.

Lerman said GW decided to delay when the school would have to pay back the $13 million because if the two cuts came at the same time, it would likely stress the business school too much.

“We tried to minimize the short-term effect because it is a tough budget year so not to add an additional burden, and give the school opportunities for growth that could then fund all that repayment rather than burdening them,” he said.

James Bailey, a professor of management, said in an email that it doesn’t appear that cuts will be made to the school’s educational programs, including curriculum revisions and the creation of an MBA geared toward analyzing digital data. He said faculty research funds would also not be impacted.

“If GWSB ‘owes’ anything, no impact on quality is discernible,” Bailey said.

Lerman suggested that travel costs be cut. One faculty member who attended the meeting said some top administrator spots in the business school would remain open for longer than usual if an official steps down. He spoke on the condition of anonymity because he thought the plan was controversial.

“[Lerman] made it clear they are not going to cut from faculty costs,” the faculty member said. “[The business school is] not going to going to slow down faculty hiring or faculty pay.”

The overspending from two years ago led to former dean Doug Guthrie’s firing in a highly public showdown over whether the school’s leaders had used money that belonged to the University. Faculty then criticized officials for taking more of the school’s revenues to pad GW’s administrative budget than previously expected.

The business school won’t necessarily have to make equal payments every year, Lerman said.

Higher education finance experts say the delay will help the school prepare for the increased expenses and prevent more deficits in the short term.

The roughly $13 million deficit was about 25 percent of the school’s budget at the time. Much of that spending went toward creating online and executive education programs, which both typically have high start-up costs but can help boost revenue from increased tuition dollars in the long term.

Robert Van Order, the chair of the school’s finance department, said the about 60 faculty members at the meeting discussed where the burden should fall. Some faculty thought the University should forgive the $13 million budget deficit altogether because it was incurred two years ago. Others argued that because the school did spend the money, it should be the one to return it.

“This isn’t funny money. This is real money,” Van Order said. “Like other debts, it should be paid back.”

But Van Order said determining how to repay the money is complicated because of factors like who is most responsible to pay, adding that it is “more like moving a big battleship than moving a jet plane.”

The business school’s current dean, Linda Livingstone, declined to comment on the how the plan’s specific timeline was created or how the cuts would affect faculty, students and the school’s programs. She was a decision maker in the repayment plan, along with Lerman, Executive Vice President and Treasurer Lou Katz and some business school staff, Lerman said.

[RLBox]

[RL articlelink=”https://www.gwhatchet.com/2013/08/22/doug-guthrie-out-as-business-school-dean-vice-president/”]

[RL articlelink=”https://www.gwhatchet.com/2015/02/02/more-budget-cuts-loom-after-graduate-enrollment-drops-again/”]

[/RLBox]

The business professor said the delay is “just to make sure the new dean is not set for failure” as she adjusts to a new school, operates under a University-wide budget cut and tries to pay back $13 million.

“So all in all, if you ask me, it is a considerate paying back schedule,” the faculty member said. “Although some of the faculty thought it wouldn’t be fair to burden the new dean with the old dean’s sins.”

The faculty member added that this repayment schedule could act as a precedent for future budget mishaps.

“The University doesn’t have any other option to make the schools pay this back,” the professor said. “Otherwise, everyone would overspend hoping the University would pick it up.”

Ramin Sedehi, the managing director of Berkeley Research Group’s Higher Education Consulting practice, said that sometimes not one entity is at fault when costs become high, and that some programs with high start-up costs just backfire. He said investments in executive education usually lead to revenue.

“Executive education has always been a major revenue feeder,” Sedehi said. “Can’t blame someone for doing them.”

The business school created a two-year program in 2012 for athletes and celebrities with a tuition price tag of $95,000, which is now defunct. It also launched four online programs during Guthrie tenure.

Business schools are also generally known to generate more revenue than other schools because of their executive programs, said Thomas Kane, a graduate education professor at Harvard College.

The business school has programs with some of the highest tuition prices on campus. GW’s executive master’s in business administration costs more than $110,000, and its standard MBA is just under $95,000.

“At lots of universities, it’s the business schools that are subsidizing other schools on campus,” Kane said.

Richard Vedder, an economics professor at Ohio University who specializes in higher education finance, said universities often give their schools an extended pay period so as not to “cripple” their finances.

“This is a monumental screw-up, and the solution actually sounds sort of OK,” Vedder said.

But in conjunction with University-wide budget cuts, he said the business school might need to make some significant sacrifices to save money. The future cuts would likely slash the administrative departments first, he said.

“Usually over the course of the years, they build up some fat in the administrative area,” Vedder said. “Some of those offices should be consolidated and eliminated.”

Mary Ellen McIntire, Colleen Murphy and Jacqueline Thomsen contributed reporting.