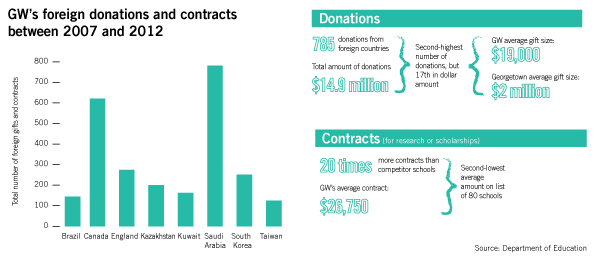

The University clinched nearly 2,300 international scholarship and research deals with countries like Kazakhstan, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan and Brazil between 2007 and 2012, according to the latest available data that GW is required to report to the Department of Education.

That’s 20 times more contracts than any of GW’s competitor schools included in the data, like Northwestern and Tufts universities. Experts say those contracts are for research projects or scholarships funded by foreign governments – two areas that have grown over the last several years as universities shift to a more global focus – and are key to raising a school’s international profile.

But GW’s average contract was worth $26,750 during that time frame – putting it second-to-last on the list of more than 80 schools, just above the University of Kentucky. A spokeswoman from the University’s research office declined to comment on why GW may be so low on the list.

Kevin Kinser, an associate professor of international higher education policy at the University at Albany, said GW’s low average may be because most of those contracts listed were for small government grants or scholarships.

For example, GW had about 100 contracts with the JSC Center of International Programs Bolash, an organization that issues student scholarships funded by Kazakhstan’s government. GW also had contracts with schools like the University of Cambridge in England and Zayed University in the United Arab Emirates.

Kinser said one reason GW may have so many more contracts than other schools is that GW officials may be more diligent about tracking the data. He also said the contracts may represent consulting work that schools do with foreign governments.

“Some institutions make these kinds of projects a significant activity because they can bring in a lot of resources for the institution and also help establish the international reputation of the institution,” Kinser said.

Philip Altbach, the director of the Center for International Higher Education and a research professor at Boston College, said the number of government-funded scholarships like the ones shown in the data have likely increased as schools have looked to expand their connections abroad.

He said many schools see international students as “cash cows” because they often come from wealthier families and can afford to pay full tuition.

“Also, the reputation aspect is very much there, as they’re trying to increase visibility overseas,” Altbach said. “It’s partly dealing with global rankings that they’re trying to improve and partly to connect themselves with more and better students.”

GW is ranked No. 194 globally by Times Higher Education on a list of 400 schools. U.S. News & World Report puts GW at No. 281 out of 500.

Officials announced earlier this year that they would push researchers to complete work overseas as securing national funding for research projects has become more competitive.

Vice President for Research Leo Chalupa declined through a University spokeswoman to provide information about the contracts, which countries GW works with most often, which schools at GW have the most research contracts or how many total international contracts the University currently has.

Benjamin Hopkins, an associate professor of history and international affairs, has won grants in the United Kingdom and a three-month fellowship at the National University of Singapore’s Asia Research Institute.

“They were not only helpful for my professional development, but also good for the University in the sense of raising its overseas research profile,” Hopkins said.

James Clark, an associate biology professor, has had a contract with the Chinese Academy of Biology since 2001 to study dinosaur fossils in the Gobi Desert. Through two $300,000 grants from the National Science Foundation, Clark has found four new species of dinosaurs and “a whole fauna of turtles, crocodiles and mammals.”

Clark said though he did not know why GW was at the forefront in number of international contracts, he was “not terribly surprised.”

The University has contracts with dozens of Chinese organizations, like the Chinese Center for Disease Control, the National Bureau of Statistics of China and Webster University in China, according to the data.

“China has exploded with science and they’re putting a lot of money into science, so it’s a really hot place to be working in science in general,” Clark said.

Included in the data were also 785 monetary gifts from foreign countries, worth $14.9 million. Though that’s the second-highest number of donations, the total amount puts GW at No. 17 on the list, behind competitors like New York, Northwestern and Georgetown universities.

GW’s average gift size was just over $19,000 – far smaller than most of the other schools on the list. Georgetown University’s average gift size was about $2 million.

Michael Nilsen, the vice president for public policy at the Association for Fundraising Professionals, said GW’s small average gift size shows “great potential.”

“Obviously, would you love to see a greater average? Sure,” Nilsen said. “It really behooves the fundraising department there, and I’m sure it’s something they’re working on cultivating.”

Nilsen said as schools like GW have tried to extend their international reach over the last several years, they may see more small gifts “because you reach out to more people on average.”

“You’re looking to throw a wider net out to students,” he said. “I’d imagine there’s more international giving as there are more international students overall.”

Nilsen said schools will try to connect with international alumni or build new donor connections as their presence in another country grows. In 2007, GW received $15,000 from its Seoul alumni club. Albert Wang, the highest individual donor, gave a total of $2 million in 2007 and 2008. Wang is from Taiwan, according to the data.

The government of Kuwait has also given GW a series of large gifts over the past several years. In 2005, Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences gave $3.4 million to establish an endowed department chair position. Three years later, the government of Kuwait put $1 million toward the Elliott School of International Affairs’ Institute for Middle East Studies.

And in 2011, the government of Kuwait gave $4.5 million to the Institute for Middle East Studies and the Global Resources Center’s Middle East and North Africa Research Center at Gelman Library.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar said officials have “increased the level of integration that occurs” between international fundraisers and international alumni relations.

In 2013, the University added two international fundraisers to its six-year-old international fundraising team. GW also hosts dozens of overseas fundraising events each year.

“We have enhanced the global aspects of our curricula and made it a priority to engage our international alumni,” Csellar said.

In the long term, that strategy might make GW a more successful international fundraiser than its peers, said Richard Ammons, a consultant at higher education fundraising firm Marts & Lundy.

“My suspicion is that over time, because they’re cultivating a larger number of donors, they’d be able to surpass the total number as average gifts increase,” Ammons said.