Updated: Feb. 23, 2015 at 3:50 p.m.

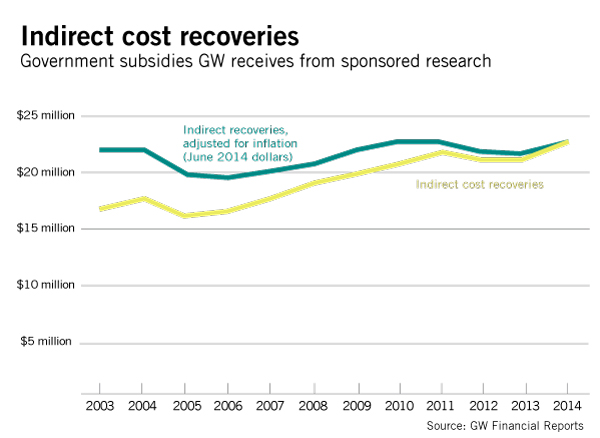

The amount the University gets as a subsidy from the federal government has barely increased in the last decade — once the number is adjusted for inflation.

Last year, GW received about $23 million in money the federal government gives as bonus funding for research qualifying for a subsidies. That’s about the same amount it amassed in 2003 when adjusted for inflation, according to Faculty Senate data released last week.

Officials count on the funds, known as indirect cost recoveries, to help cover the costs of research – like paying for equipment, keeping laboratory lights on and hiring staff. Faculty leaders say they are concerned that in a tough research funding environment where not all projects can earn cost recoveries, GW may not see a substantial growth in funds in the future.

“It does concern me,” said Donald Parsons, an economics professor and a member of the Faculty Senate’s finance committee. “It would suggest it might be time to sit down and think about how we’re organizing things. Maybe flashy things aren’t as important as how we’re administering projects.”

Parsons has been a longtime critic of the University’s investment in the $275 million Science and Engineering Hall, which officials have argued will help boost GW’s research reputation and portfolio.

He compiled the data to counter numbers that Vice President for Research Leo Chalupa presented at January’s Faculty Senate meeting, which showed a 44 percent increase in indirect cost recoveries since 2003. The $23 million GW accrued last year was the largest total in a decade.

“I contributed by pointing out it’s not like wonderful things are happening with all of this glittery stuff his office is throwing out,” Parsons said.

So far this fiscal year, the indirect cost recoveries that GW has received have increased 13.2 percent compared to the first half of fiscal year 2014 – the greatest increase ever for that time period, according to Parsons’ data.

Chalupa said in an email that though the amount of funding distributed by the National Institutes of Health has decreased 17 percent since 2003, the University has increased the grant money it gets from the federal government as a whole. GW’s research expenditures also beat officials’ expectations last year, growing 11 percent.

“The growth and progress we are experiencing in this increasingly competitive market is a testament to the quality of our research and the success of our faculty,” Chalupa said. “We are pleased that we are outpacing other universities in research expenditure growth in an era that is seeing more schools and colleges compete for less available money.”

The University has set its sights on expanding its research portfolio over the next decade, and in the past, officials have hoped to bring in about $30 million a year in indirect cost recoveries. To push professors to do more research, GW doubled the amount schools can bring in for research subsidies.

Chalupa said earlier this year that he hopes to grow the amount the University brings in through those funds by about 3 percent each year.

But Parsons’ data also shows what Charles Garris, an engineering professor and the chair of the Faculty Senate, called the “dirty little secret” behind spending research dollars: Not all of the projects GW takes on bring in indirect cost recoveries.

For example, last fiscal year, the University spent nearly $9 million on a NIH-funded Capital Project award that brought in no cost recoveries, according to the original research report. The year before, GW put nearly $5 million into that project.

“Then you have to deal with people and activities, and you’re in charge of it and you have your office and expenses,” Garris said. “One of the key questions is, ‘Is the University getting anything financially?’ You do get a lot of things from a contributing-to-society point of view and you do get recognition. But financially, we don’t get much.”

Joseph Cordes, the chair of the Faculty Senate’s finance committee, also said the competition for federal government grants has strained GW’s research aspirations.

“On the whole, you have more institutions competing for a basically flat or somewhat declining pool of research dollars,” Cordes said. “So in that sense, GW is in a market now that has become even more competitive for dollars.”

But Mark Edberg, an associate professor and center director at the Milken Institute School of Public Health’s department of prevention and community health, said because the school’s new building is the center of most research, it has been able to double the amount of indirect cost recoveries it can receive on federally funded grants using the campus rate for cost recoveries. That rate also includes what would have been rent payments in the old buildings and helps cover the costs of facilities.

In 2012, Edberg received a five-year, $5 million grant from the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities to address health issues in a Latino community in Langley Park, Md. and other immigrant populations.

“I think at GW in general, not just the public health school, the research profile has increased over the past number of years,” Edberg said. “We have a new public health school building, new science and engineering building. There’s a symbolic element to them, but also an element of presenting that we have an infrastructure now that we may not have had before.”

Still, some professors say the money that comes back to GW is not what motivates them to do the work.

Johan van Dorp, a professor of engineering management and decision sciences, completed a traffic risk assessment study in 2008 worth $1 million. But van Dorp said neither the grant nor the return to the University was the reason he decided to do the project.

“Would it incentivize me more to do research if more would come back into my pocket? I don’t necessarily think so. That’s not the reason I do it in the first place,” van Dorp said. “Ultimately, the cost recovery is not a reason for me to do the research.”

Chemistry professor Houston Miller said though “one would expect that if the research expenditures are increasing rapidly, so would the indirect cost recovery rate,” GW still benefits from an expanding research portfolio.

Miller said he had “zero doubt” that the Science and Engineering Hall, which officials had initially planned to fund partially through indirect cost recoveries, will continue to spur research at GW.

“The building is buzzing with activity as our labs come back up to speed,” Miller said. “Will indirect costs pay the bills for this massive investment? Probably not, but that is not the point.”