The millions of dollars the University will have to spend on debt payments over the next 30 years will likely put hiring, scholarships and future construction projects at risk, a Faculty Senate report found.

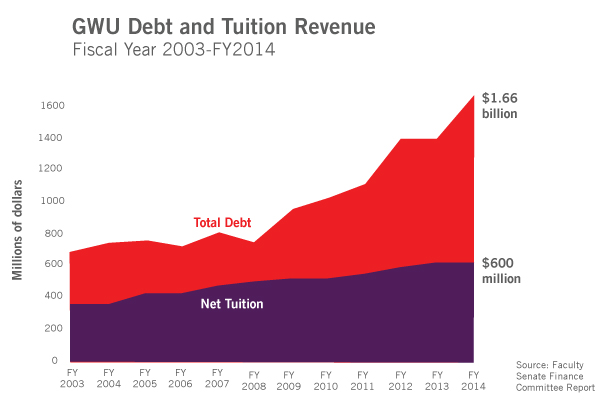

The Faculty Senate’s finance committee reviewed a report last week that found the University’s $1.66 billion debt load will come at the cost of future growth. The report explains that to focus on shrinking its debt, officials will have to usher in a period of cutbacks.

Economics professor Donald Parsons, who wrote the report as a member of the Faculty Senate’s finance committee, concluded that if the University followed a 20-year “regime” to pay back the debt, officials would have to use the equivalent of a quarter of its tuition revenue, about $150 million yearly.

That’s equal to hiring 75 tenured professors in a year or giving 2,500 students a full-ride scholarship. It’s also about equal to the size of GW’s financial aid pool, about the cost of its newest residence hall and the amount the University brought in through commercial rent last year.

“It was meant to illustrate how massive the debt has become,” Parsons said. “That means things aren’t going to be bought for students, faculty. But we’ll have the buildings – that’s the offset.”

The report says the spending diet would be worth it because then the University would be free to invest in other areas in the future. Until that happens, Parsons said GW will be in a holding pattern, which is a problem for a school trying to boost its reputation and compete with more financially well-off institutions.

Parsons said part of the problem with glitzy buildings like the $275 million Science and Engineering Hall is that, by the time officials finally do pay off the construction costs, it will be time for another round of updates.

“There’s no sensible way we could pay it back over the lifetime of the buildings they’re building,” Parsons said. “A massive renovation would have to occur somewhere in there.”

[RLBox]

[RL articlelink=”https://www.gwhatchet.com/2013/05/19/seh-funding/”]

[RL articlelink=”https://www.gwhatchet.com/2013/11/11/the-ups-and-downs-of-being-one-of-d-c-s-richest-landlords/”]

[RL articlelink=”https://www.gwhatchet.com/2014/02/10/faculty-leaders-cast-doubt-on-gws-plans-to-pay-back-1-4-billion-debt/”]

[RL articlelink=”https://www.gwhatchet.com/2014/10/27/as-opening-nears-for-science-and-engineering-hall-how-much-does-gw-need-to-raise/”]

[/RLBox]

GW will pay $66 million this fiscal year to cover the interest on its debt, the largest total yet and about equal to the amount it can use from its endowment every year. That interest payment grew 16 percent from the previous year.

The University’s debt load grew again last summer when officials decided to take out $300 million in new debt to help pay for construction projects and refinance some bonds. The funding plan for the recently completed Science and Engineering Hall will also keep GW making debt payments for the next 30 years after officials failed to fundraise enough for construction costs.

Joseph Cordes, an economics professor and the chair of the Faculty Senate’s finance committee, said the “underlying question” is whether the activities financed by debt, like construction, are outweighed by the other areas in which the money could be spent.

“If the aspirations that lie behind the activities that are financed by debt are realized, then the debt will have been a good investment. If not, not so much,” Cordes said.

In a separate report Cordes presented to the Faculty Senate earlier this month, he found the University’s net assets have also increased more than 28 percent from fiscal year 2010. Cordes said that is one indicator that GW is in “overall good financial shape.”

Still, operating expenses have grown almost twice as fast as the rate at which revenue increased during fiscal year 2014, leaving it without much of a “cushion,” Cordes said. That thin margin has also worried credit rating agencies, which again warned officials this past summer that the strain of GW’s debt load – coupled with its slow-growing revenue – could lead to a lower rating in the future. The University relies on tuition for about 60 percent of its revenue.

Making debt payments will take away money that could have been spent on other important areas, affecting “pretty much everything,” said John Wiley, an education professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who specializes in higher education finance.

“Everything will be hampered by the huge debt burden,” Wiley said. “The opportunity cost is pretty much everything the university does – student scholarships, hiring and retaining high-quality faculty, seeding new research efforts and maintaining the buildings they’ve already got.”

As universities like GW invest in building high-quality facilities to compete for the best students, Wiley said “a lot of schools” will face the same issues down the line as they pay for those projects. GW’s construction boom began under former University President Stephen Joel Trachtenberg, who looked to elevate the school’s reputation by adding top-notch buildings to lure students.

Though buildings may put a financial strain on schools, some experts say they’re worth it because facilities are what potential students and hires first see. Most of GW’s current debt stems from the construction boom that has evolved over the past several years.

“It’s not just housing it’s the entire experience. Students come from high schools and they’re looking at where they want to go to school, they want the whole picture,” Trachtenberg said.

Executive Vice President and Treasurer Lou Katz declined to say whether GW will take out more debt down the line.

“The University takes a long-term view of its financial strategy and will continue to focus on areas that make GW a great institution,” Katz said.

For the past several years, the University’s debt strategy has centered on only paying back the money it owes for the annual interest payments on its debt. That means GW hasn’t made a dent in the actual money it owes, though officials say that’s acceptable because they are taking advantage of historically low interest rates.

Ann McCorvey, deputy vice president and treasurer, said she did not understand “the linkage” between GW’s debt payments and its other expenses.

Dennis Jones, the president of the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems said schools should dedicate portions of their budgets each year to make upgrades to buildings, as raising money down the line for major renovations is a nearly impossible task for fundraisers.

“Fundraising for renewal of buildings is really hard. And once it’s got a name, it’s hard to go get money to renew a building that already has somebody else’s name on it,” Jones said.

The University has historically struggled to land large gifts for building projects, though the tide started to turn when it received a combined $80 million gift for the public health school from philanthropists Sumner Redstone and Michael Milken last March.

But Jennifer Delaney, an assistant professor in higher education policy at the University of Illinois at Urbana – Champaign, said buying into the “higher education arms race” can be tricky for schools like GW, which don’t have endowments nearly as large as more prestigious schools. Northwestern University, a peer school, has an endowment five times the size of GW’s.

“There’s constant need for upgrading and needing new facilities and the newest, nicest lab space. Once you engage with that, you can’t ever stop,” Delaney said. “GW is an institution that stands out as really aggressively going after building of campus and amenities to move it into that marketplace.”