Pascale Ehrenfreund first began planning how to land a rocket on a comet in 1996, and almost two decades later, she got her chance to celebrate being a part of the first team to succeed.

Ehrenfreund, a professor in GW’s Space Policy Institute, was one of the many researchers helping to run the groundbreaking project that landed a rocket on the comet Wednesday more than 300 million miles away from its launch site on Earth. Her colleagues say her success will draw in the next generation of space policy and technology experts to GW.

“Space research is a risky business,” Ehrenfreund said. “We are exploring the origin of our solar system, understanding all existence.”

Ehrenfreund developed two instruments for the mission, including one on the Philae lander that will search the comet for complex molecules that are necessary to sustain life. She also helped develop a microscope that will analyze individual grains of dust on the comet from a satellite that will follow the comet on its journey around the sun.

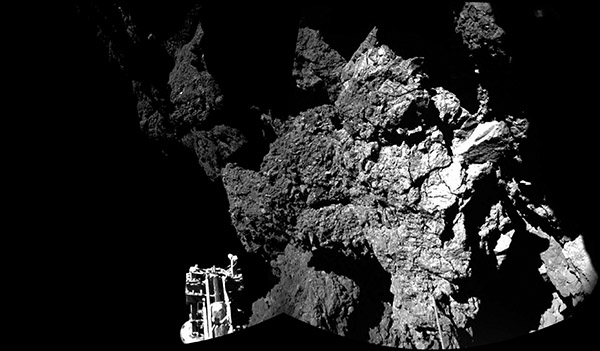

But the celebration was short-lived: Friday, the lander fell asleep after accidentally hopping into a spot in the shadow of a cliff that blocks the sunlight from hitting its solar-powered batteries.

The lander was still be able to transmit information from the comet’s surface, and scientists managed to slightly move the spacecraft to expose it to more sunlight. They say it may reawaken next year as the comet moves closer to the sun.

John Logsdon, who began the Elliott School of International Affairs’ Space Policy Institute in 1983, said Ehrenfreund’s experience was a clear demonstration to students of how they could bridge the policy and technological aspects of space research.

“Having someone like professor Ehrenfreund, who has one foot very deeply associated in the science and technology of space, and another to the policy side really adds another dimension,” he said.

Over the past 18 years, Ehrenfreund has also conducted individual research on various aspects of space, including data collection from two satellites, and has served as president of the Austrian Science Fund since 2013.

She is the chair of the exploration panel in the Committee On Space Research, a group of international scientists, and is a member of multiple advisory boards of the European Space Agency.

Logsdon said Ehrenfreund’s other accomplishments, including projects on the International Space Station, have proven her to be a valuable part of the small program, and he said she was a unique asset in an institute otherwise made up primarily of analysts.

“It also adds a richness to what we do,” he said. “She flies around the world, her real office is an airplane. But when she’s in residence she interacts with our students.”

High-profile projects can build up the reputation of the institute, which already draws top names and speakers, including astronaut Buzz Aldrin and NASA Director Charles Bolden – both of whom have spoken to or will speak to classes this month.

Peter Hays, a professor of space policy and international affairs, said the institute was one of the top programs in the country, and that it offered opportunities no other school could.

“Nothing else like it has such high-level access to policymakers and has such a comprehensive look at space policy,” he said. “We’re shaping the policy in fundamental ways. There’s no other place to do that.”

He said his former students have gone on to complete projects like writing Japan’s new space laws.

David Alexander, director of the Rice Space Institute, said successful projects generate more student interest in different areas of space studies.

“It’s great for them to see that they’re not working as geeks in the corner that nobody talks to,” he said. “They see the kind of education and work it takes to create these kind of things.”