Updated: Oct. 10, 2014 at 12:20 a.m.

The Trachtenberg administration’s last dean is stepping down.

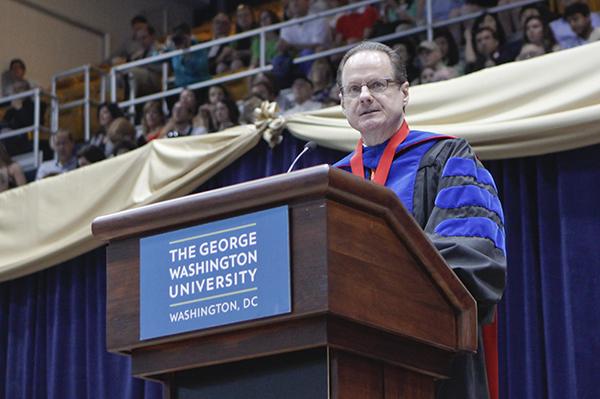

When Elliott School of International Affairs Dean Michael Brown leaves his position this spring, he will give University President Steven Knapp the opportunity to confirm a leader in the school most consider to be GW’s crown jewel. Brown was the last dean from former University President Stephen Joel Trachtenberg’s 19-year tenure.

It will also mark the end of one of the longest deanships in recent University history: Brown, who came to GW in 2005, has led the Elliott School for roughly twice as long as the average GW school leader.

It’s a big moment when a college president rubber stamps the faculty’s choice for a dean in every school, since the president’s vision is embedded in a new dean’s mind when he or she arrives on campus, several higher education experts said.

A president will typically replace all the deans his predecessor had named by asking some to leave and waiting for others to choose to step down, said Sharon McDade, the former director of the American Council on Education’s Fellows Program.

“All the people that have been hired into a senior academic leadership role have been hired to make sure they’re of the same mindset of the institution and how that should be executed,” said McDade, who is a consultant at the executive search firm Greenwood-Asher and Associates.

In a way, Brown has become one of Knapp’s deans, serving most of what will be his decade-long tenure under the current University president. Still, his stepping down leaves just a handful of top administrators approved by Trachtenberg in Knapp’s cabinet.

For the third year in a row, the University will begin a search for another dean, and Brown’s replacement will be GW’s fifth new dean in three years.

As he steps down, GW will lose one of its most successful leaders. Brown has more than doubled the Elliott School’s endowment over the past decade and doubled the number of research institutes within the school, the University’s second largest.

“He’s brought it to new heights, with recruiting a world-class faculty, starting new programs, further improving the curriculum and offerings we have for undergraduates and graduates,” said Steven Skancke, chair of the Elliott School’s board of advisers. “We’re just grateful that we would have had him for ten years. It’s a long time for people like Mike to be here.”

A decade of leadership

Brown arrived at GW as the Elliott School was solidifying its place as one of the University’s most celebrated colleges, and has led the international affairs school as top administrators have pushed a more global approach across programs.

The Elliott School has been consistently recognized as one of the nation’s top international schools, with Foreign Policy magazine ranking undergraduate and graduate programs at the school ninth and seventh in the country, respectively.

Brown has brought more than 20 new faculty members to the school over the past decade and was noted for being able to recruit prominent figures in the field of international affairs to GW, like economist James Foster and anthropologist Christina Fink.

His predecessor, Harry Harding, spent 10 years at the helm of the school and changed its reputation from what one professor described as “mediocre” to one of the most prestigious in the country. But over the past nine years, Brown was able to elevate the school further.

“Everyone in the community sees us in the top three [international affairs schools],” said David Shambaugh, director of the school’s China Policy Program. “But there are measures that you can’t count like collegiality.”

He added that students are now choosing the Elliott School over other top international affairs schools, a trend that has only begun during Brown’s tenure.

Provost Steven Lerman declined through a spokeswoman to answer questions about when a search for Brown’s replacement will begin. A committee made up of faculty, students and some administrators will likely spend the winter reviewing and interviewing candidates and invite the top candidates to campus in the spring.

Brown will stay on as a faculty member, but will likely take a sabbatical during his first year away from the dean’s office.

“The issue of war and peace led me to start studying international affairs many years ago. Security and conflict problems have become intense and complex in recent years, and I would like to do what I can to shed more light on them,” Brown said. “If world peace breaks out, I will be out of a job.”

Before coming to GW, Brown was the director of Georgetown University’s Center for Peace and Security Studies, and an expert in security and conflict resolution. A prolific writer, he has authored or co-authored 21 books and is a member of the editorial board for the journal International Affairs.

A turning point for Knapp

Knapp, an English scholar who served as the provost at Johns Hopkins University before coming to GW, brought a new set of priorities to GW that have become clear when choosing deans.

Deans’ responsibilities have also shifted since Knapp took over in 2007. He has required school leaders to spend at least 40 percent of their time fundraising, and deans have taken on more administrative responsibilities.

Knapp initially chose deans with big ideas that could shake up some of GW’s most prominent schools as he looked to launch new, noteworthy academic programs across the University. After three deans abruptly left their positions within two years, he has looked for leaders with more experience and research skills on their resumés to steady programs.

By keeping Brown on as the leader of the Elliott School, Knapp showed his trust in Brown to carry out his vision for GW within the school, Trachtenberg said.

“When you come in as a new president, if you’re really unhappy with the sitting dean, you generally sit down with him or her and work out a departure, so if somebody stays on after you have been president – particularly if they stay on for a couple of years – they become your deans,” Trachtenberg said.

Charles Garris, the chair of the Faculty Senate executive committee who has served as an engineering professor at GW for about 30 years, said Knapp has looked specifically for deans with strong fundraising potential, which Trachtenberg did not make a top priority.

Knapp ultimately chooses a dean from about three finalists selected by the school’s search committee, which Garris said can limit the potential for major differences between their dean picks. Still, he pointed to former Columbian College dean Peg Barratt as someone chosen by Trachtenberg who had a strong research background, but not the fundraising skills Knapp values.

“She wasn’t the outgoing person to generate lots of funding,” Garris said.

The final dean candidates who visited campus last spring in the searches for leaders of the business and law schools met with Michael Morsberger, vice president for development and alumni relations. That layer was added to the dean hiring process after Knapp’s arrival.

Scott Jaschik, co-editor of Inside HigherEd, said the president’s choice in a dean demonstrates his vision for the University and the school he has chosen to lead, since the dean oversees the creation of new programs or initiatives in schools.

“The appointment of a dean is one of the most crucial things that presidents do,” he said. “The way the president ultimately sets the direction is with appointments of deans, because the deans are the ones working with the faculty in the colleges to construct the curriculum and carry it out.”

Losing the longest-serving dean

Brown has been in his post longer than any of GW’s other academic leaders, and has also remained in his position longer than most college leaders nationwide, who spend about five years in administrative roles before returning to the classroom and focusing on their own research interests.

McDade, the executive search consultant who is also a former GW professor of higher education, said presidents will typically keep on administrators from their predecessor’s cabinet so long as they are of the same mindset and energy that the new administration values.

“‘Does it look like someone I can collaborate with in a high level of efficiency?’ they ask,” she said. “Clearly they both decided that all those things were in line.”

Brown’s longer-than-average tenure allowed him to build up major fundraising success, more than doubling the school’s endowment to $44 million and bringing in funds for endowed professorships, research centers and other faculty initiatives.

Don Lehman, GW’s former executive vice president for academic affairs, said Brown’s most noteworthy accomplishment – launching new research centers that had helped bring more national and global attention to the international affairs school – would set up his predecessor to continue elevating the school’s reputation.

“He’s taken the school to the next level, and so his successor will have a completely different starting place,” Lehman said.

This post was updated to reflect the following corrections:

In a graphic, The Hatchet incorrectly spelled the name of the dean of the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences. It is Ben Vinson, not Ben Vincent. The Hatchet also misidentified Sharon McDade as the director of fellowships at the American Council on Education. She is the former director of the ACE Fellows Program. We regret these errors.