While the University has transformed itself with new buildings and research centers over the past decade, one change has driven up costs beneath the surface: a rush of administrative hires.

The number of administrators – holding positions from vice provost to associate dean – grew 44 percent between 2004 and 2012, according to data released this month. Meanwhile, GW has kept hiring relatively flat for full-time professors, part-time professors and support staff.

“It seems like you’re having lots of chiefs but no Indians,” said Charles Garris, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering who has spent 36 years at GW.

Salaries and benefits for employees make up one of the University’s fastest-growing costs of its roughly $1 billion operating budget, which has grown by 71 percent since 2001. Administrators are usually the highest-paid of that employee core, with six-figure salaries going to deans, vice presidents and top financial officers.

Faculty Senate leaders have warned that bringing on middle- and top-level officials will keep driving up costs – and tuition. Provost Steven Lerman said last May that GW would dig deeper into the cost of administrative bloat at GW, but he and other officials said they do not yet have updates on the study.

Lerman said last week most of the new administrative hires have been strategic – with the goal of improving the University’s fundraising, counseling and career services. He added that GW has hired more research officials to help faculty nab grants and navigate complex regulations.

“When people talk about administrative growth, sometimes it’s just people filling out paperwork and sometimes it’s people students have lobbied for,” Lerman said.

The growth may also be the product of GW’s rising ambitions. Columbian Colleges of Arts and Sciences, for instance, has mulled the hire of more vice deans to allow the college’s top leader, Ben Vinson, to focus more on fundraising.

Administrators are also planning for faculty hires to catch up, with a net increase of 42 professors this year, and 50 to 100 more planned over the next decade. The Innovation Task Force also plans cost-cutting strategies, like moving some administrative offices to the Virginia Science and Technology Campus.

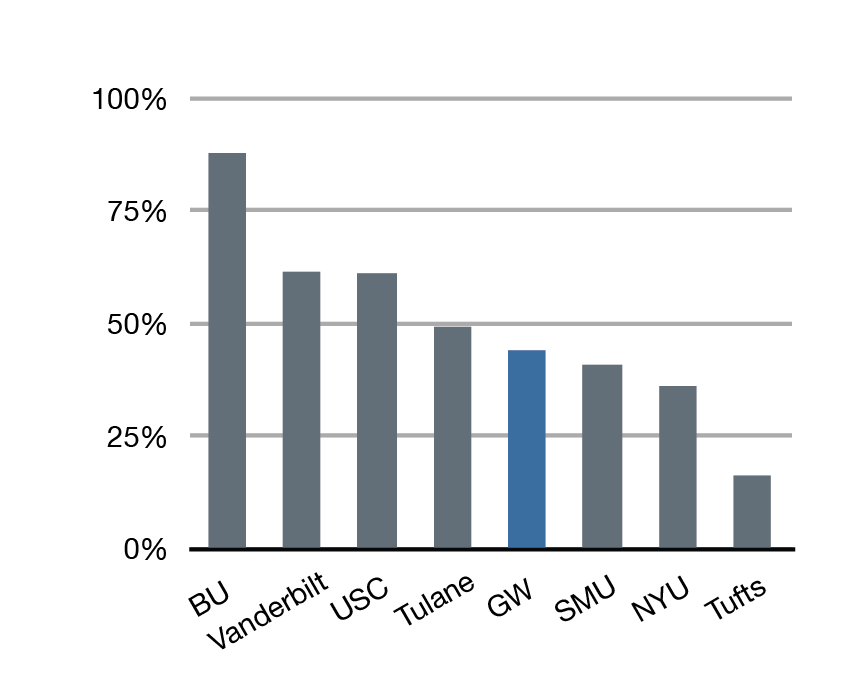

The University’s hires outpaced many of its peer schools, including New York and Southern Methodist universities. Out of the 14 universities, Washington University in St. Louis has seen the most rapid growth, doubling its administrative positions since 2004.

The data was released by the Delta Cost Project, a research group that focuses on college affordability. It pins some of the blame for rising tuition nationally on colleges hiring more non-faculty, who carry generous pay and benefit packages.

The group classifies administrators as working in “positions where work is directly related to management policies or general business operations of the university.”

“Many of these new positions appear to be providing student services, but whether they represent justifiable expenses or unnecessary ‘bloat’ is up for debate,” the Delta Cost Project published in a report this month.

Lynn Goldman, dean of the School of Public Health and Health Services, said the school has hired several new staffers since she arrived in 2010 to help make sure the school’s growing research profile complies with federal regulations and help students nab jobs.

The administrative growth may also create lighter workloads for faculty.

Paul Swiercz, a professor of management who specializes in human resources, spent several Faculty Senate meetings last year lobbying officials to take on the issue. He said that at GW, administrators are being added to take over roles and tasks that traditionally belong to faculty.

“As staff has grown, there’s a natural question of whose job is it that is bumping into the traditional boundaries of faculty responsibilities,” Swiercz said.

Michael Feuer, dean of the Graduate School of Education and Human Development, said increasing management across the school put less pressure on faculty, who have to balance teaching, research and leadership posts.

He said by introducing new management reforms over the next few years, faculty would be able to work together more easily on research and new instructional innovation.

Garris, who came to GW in 1978, has seen the expanding cabinets of two administrations, compared to the “lean administration” of the University’s previous leader, Lloyd Elliott. He remembers former University President Stephen Joel Trachtenberg adding more vice presidents and University President Steven Knapp growing the provost’s office.

Since 2011, Knapp’s cabinet has added four vice president positions and at least five vice or assistant provost positions, though some of the officials have left their spots.

“They’ve got all these big shots and it’s not clear to the faculty exactly what they do,” Garris said.

Colleges nationwide have felt pressure to ramp up services as more students arrive on campus with customer mindsets, administrators have noticed.

Last year, the University spent $32,860 per student, with more than a third of that going toward programs and services. Long-serving administrators have defended GW’s high spending over the years because it helped increase the school’s selectivity and bring in top students looking for amenities and services like academic and career advising.

Benjamin Ginsberg, a Johns Hopkins University professor and author of “The Fall of the Faculty: The Rise of the All-Administrative University and Why It Matters,” said faculty believe teaching and researching should be top focus of universities, while administrators are more concerned with making money so the college can run.

“Teachers are the purpose of the University that’s supposed to promote teaching and research. But to administrators, that’s different. The purpose of teaching and research is to bring customers to the store,” he said. “The ends and means of higher education are reversed.”