Shawn McHale is an associate professor of history and international affairs.

When Nelson Mandela died in last December, the internet abounded with news of his passing. World leaders praised the man, including the last white Prime Minister of South Africa, F.W. de Klerk.

But along with the praise came a wealth of racist diatribes against Mandela. And it was by tracking down some of these bigoted comments that I uncovered a forgotten, yet once-prominent racist who graduated from GW.

It is no secret that the University has a past deeply shaped by race. For much of its history since 1821, GW was a quintessentially southern school in a southern city.

Until the 1960s, it rarely accepted black students. While the university appears to have admitted its first Asian student in the 1860s – a student from Burma – it worked to exclude black students. After World War Two, little had changed: As a black professor at Howard who attended GW in the mid-1960s told me, at that time, “you could count the number of African-American students at GW on one, maybe two, hands.”

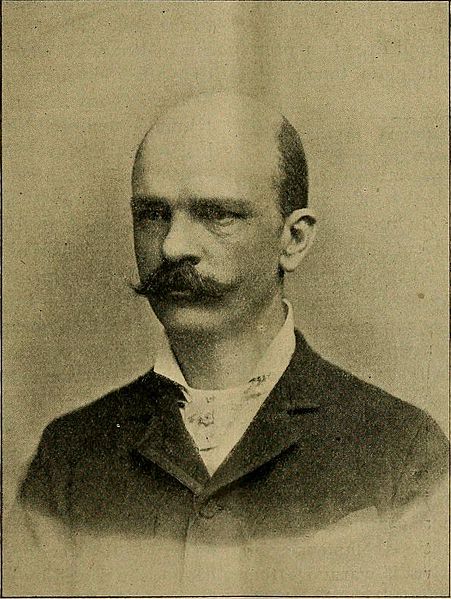

This is where the forgotten history of GW comes in. Robert W. Shufeldt, who graduated from medical school here in 1876, was both a well-known ornithologist and a writer of popularized racist publications. I “discovered” him, so to speak, when I came across his racist statements quoted in reader comments on news stories on Mandela. Intrigued – and horrified – I tracked these quotations back to two Shufeldt books: “The Negro: A Menace To American Civilization” (1907) and “America’s Greatest Problem: the Negro” (1915).

Thanks to the internet, the white supremacy embodied by Shufeldt that had once fallen into obscurity seems to have been resurrected. A variety of white supremacist and “Christian identity” websites contain links to or copies of his books. No wonder: Shufeldt had a fascination with lynching. In “The Negro Menace,” he stated that “the negro has no morals” and was “a lazy, ignorant, criminal race.” He abhorred what he called “hybridization” between the races and argued that there was only one remedy for the “Negro problem:” complete deportation to avoid a “race war.”

Shufeldt’s legacy seems to be two-fold. Department of Vertebrate Zoology at the Smithsonian Institution, apparently oblivious to his views on race, has him listed on its “hall of fame.” Contemporary racists today, however, focus on his books on race. To members of the University community, Shufeldt’s agitation for race separation should remind us of this University’s broader historical legacy on race.

As we move forward to the 200th anniversary of the founding of this University in 2021, the least we can do is learn more about the segregated past of this institution and make commitments to being inclusive.

As a start, why not rename the Marvin Center, named after a segregationist president of this University?