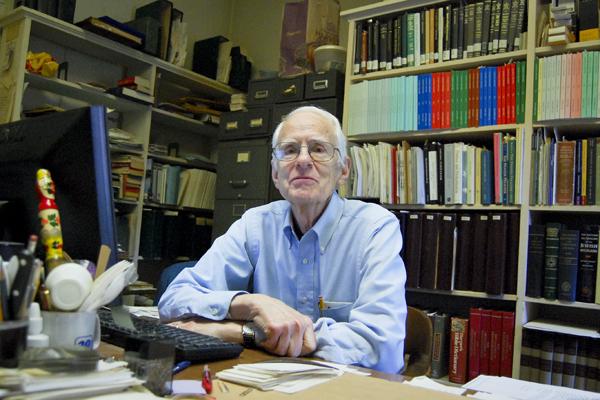

Hundreds of books burst from shelves, congest boxes and compress the five worn, mismatched seats in professor Dewey Wallace’s 2106 G St. office.

Some chronicle Wallace’s speciality, Christian history. Others focus on contemporary theology or era-specific religious studies. His post-retirement plans, then, are not surprising: “No big, dramatic plans,” Wallace said. “Just catching up on my reading.”

The 77-year-old professor, known for his dry humor and wit, will retire after 50 years in the department of religion, which included a brief stint as department chair three years ago. His career spans five decades within only one university in a department he described as “comfortable and happy.”

In that career, Wallace has authored multiple books and seen changes in public religious attitudes, but colleagues maintain that the professor’s teaching acumen and scholastic standards have remained constant.

Robert Eisen, chair of the department of religion, described Wallace as “a perfect colleague and first-rate scholar.” Calling the religious studies department a “hidden gem” of the University, Eisen credited Wallace as instrumental to the program’s growth.

“I’m not a believer that you have to stand on your head or do acrobatics in class to be a great or unique professor,” Eisen said. “Sometimes just the ability to clearly present material, get students to think creatively, and give them new ways of thinking is what makes you unique. Dewey does all that very well.”

Wallace was awarded the prestigious Oscar and Shoshana Trachtenberg Prize for Teaching Excellence in 2007, a moment he recalls as his “proudest” in his University career. In 2001, he received the Bender Teaching Award, which recognizes professors notable for setting high academic standards and consistently intellectually engaging students.

While Wallace’s curriculum, which focuses extensively on the history of Christianity and religion in the U.S., has hardly wavered, the intellectual attitudes of his students across generations have varied.

Under Lloyd Elliott’s GW presidency during the mid-1960s and 1970s, the University saw an uprising of students facing tear gas for protesting the Vietnam War.

“In my early years here, in the late ’60s, the radical ’60s, there was a good deal of student disruption and disorder on the campus, and that made for a very intellectually exciting atmosphere,” Wallace said. “Students were pretty adventuresome in the ideas they were interested in probing, maybe moreso than now.”

Today, Wallace observes dwindling attention spans — “the big lecture hall [environment] is less palatable now” — and a shift in student motivation.

“Now students are compelled just by such things as the economy, to be very focused on a career and preparation for that career, and maybe a little less intellectually adventuresome than some earlier student generations,” Wallace said, adding, “but there are always exceptions.”

As students focus on a degree’s worth in the professional sphere, Wallace noted an increase in students pursuing double majors within the department, many in pre-med and pre-law studies. The department also expanded to house the Peace Studies Program.

Wallace sought out diverse scholarly research for his students, warmly acknowledging the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Library of Congress as his favorite District resources.

“You try to engage students by showing them that the issues that have been discussed in the story of religion, in all religions through the centuries, are issues that are still compelling ones if they just try hard to grasp it,” Wallace said. “In earlier ages, they were discussing similar problems in a different language or through a different set of lenses.”

Eisen lauded Wallace’s commitment to conveying the salience of religious studies in modern society.

“I don’t think there’s a subject that’s more relevant in the world today. Just pick up any newspaper,” Eisen said. “No American student can call themselves educated if they don’t know about world religions, because religion divides us and unites us both in America and abroad.”

As he leaves a department he helped mold at the one university he remained loyal to throughout his professional life, Wallace said he hopes his legacy is one that emphasizes conscientious teaching and a commitment to research.

The beneficiaries, he hopes, are the hundreds of students he’s instructed throughout his exhaustive career.

“We should not forget the importance of teaching, and that much of our pay comes from student tuition,” Wallace said. “We should be mindful of that.”