These days, the very mention of the Student Association to the average GW student evokes a roll of the eyes or, at bare minimum, an annoyed chuckle.

In fact, it seems the only thing students might think is more ridiculous than the Student Association is a recently launched campaign to abolish it.

The funny thing is, people have tried to abolish GW’s student government before. And it worked.

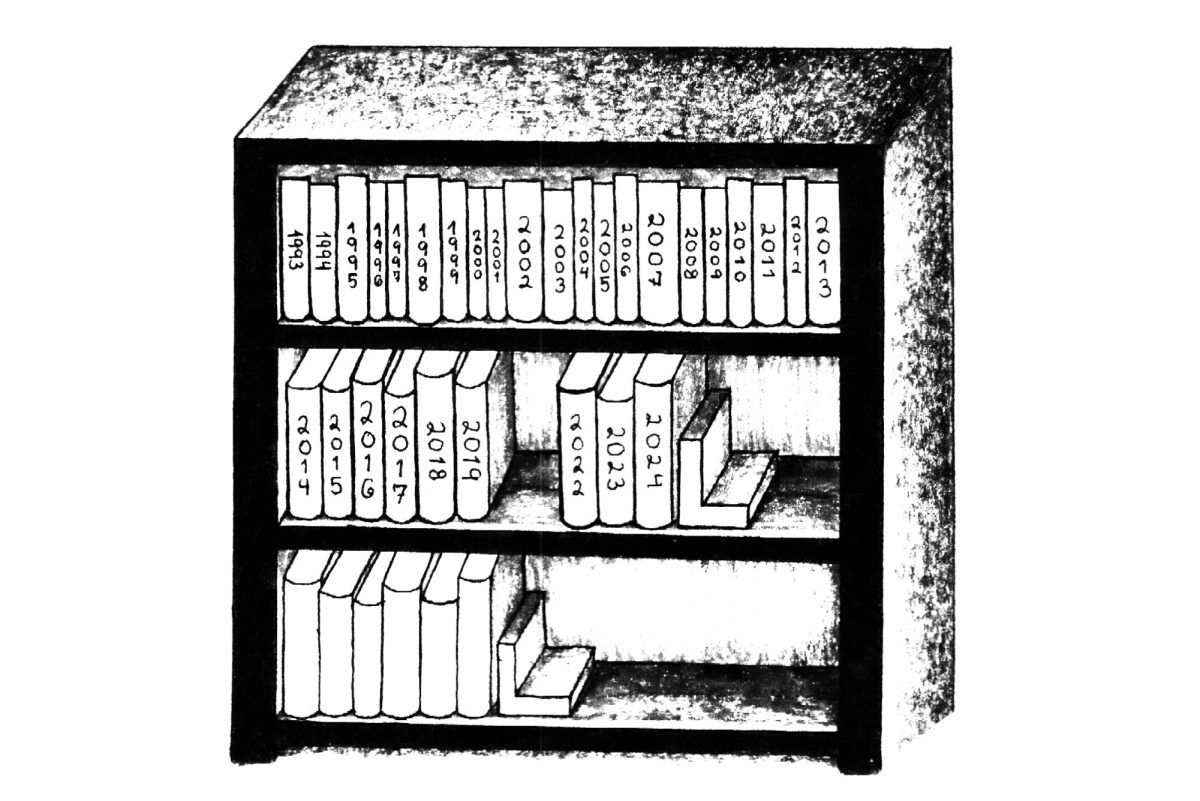

In the wake of the Vietnam War protests in the mid-sixties, momentum began to build around the idea that the SA – then called the Student Assembly – was severely flawed. In a 1969 Hatchet op-ed, SA President Neil Portnow cited both the SA’s exclusion from the University’s decision-making process and a lack of communication between senators and the student body as reasons for its ineffectiveness. Portnow abandoned his optimism for general reform and ran for re-election on a one-issue platform: abolish the SA.

Portnow won re-election and kept his word – Feb. 27, 1970, the SA voted to dissolve itself.

The goal was to establish an All-University Assembly in the SA’s place, one that included students, faculty, administrators and alumni in one decision-making body. While great in theory, the idea was unfounded in reality; it lacked the political support of any key players and ultimately went nowhere. In 1974, the Board of Trustees almost unanimously shot down the idea of the AUA.

Fed up with going almost half a decade without representation, students then pushed for a constitutional convention and, 2 years later, the Student Association was born.

A history of frustration with the SA

Today’s Abolish the SA campaign may seem radical, however, the notion of abolishing the SA is by no means a novel concept. It also begs the question of why, year after year, there are still students pushing to eliminate their own representation.

The answer is not all that crazy. Just like its predecessor, the current SA serves to do two purposes: allocating student funds and advocating for student interests. But it is also plagued by many of the same problems it was decades ago.

The SA still has no vote to form University policy. Instead, it only has the opportunity to lobby the administration and the Board. Despite living in the age of Facebook and Twitter, there is still poor communication between SA senators and the student body. By and large, senators do not actively seek feedback from their constituents, nor do they inform the student body of important accomplishments or efforts. To exacerbate it all, students are still largely apathetic, meaning that SA senators are often elected with just a few hundred votes. Chris Clark, the SA Senate Finance Committee chair and a University-At Large senator, who has significant control over the roughly $1 million in student funds allocated this year, was elected by only 15 percent of the undergraduate student body in last spring’s elections.

The SA is imperfect, and this is something that its members openly admit. And so year after year, SA candidates run on a platform of reforming the SA, but that change rarely materializes.

Instead, the Student Association, bound by strict limits and vested with little power, often becomes no more than an internally dynamic organization – institutional revisions sometimes become the closest step to reform.

Flawed impetus for change

Sophomore Phil Gardner, the founder of the 2011 Abolish the SA campaign and current SA presidential candidate, claims that in its 35-year life, the SA has never influenced a major University decision.

I disagree with this assertion – the push for co-ed dorms in the 1970s and for better Columbian School advising in 2010 were certainly major University decisions. But it also ignores the nature of the SA’s advocacy role. Oftentimes the most effective lobbying happens behind closed doors to leverage the possibility of public pressure or use personal relationships to get things accomplished quickly. Through these efforts, particularly from individuals in the SA’s executive branch, important headway has been made on issues from Gelman renovations to J Street.

In theory, resolving the salient issues on campus could be lobbied for by any student, so there is certainly an argument for disbanding the current form of student government. But the important question is what would come in its place.

Gardner believes the two SA tasks could be re-assigned to existing entities. For student-fund allocation, he proposes the Program Board or Marvin Center Governing Board assume the responsibility. Regarding student advocacy, he suggests handing it over to the Joint Committee of Faculty and Students, a 12-person body of students and faculty that collaborate to identify and solve problems on campus. Gardner argues that the six students on the committee can meet informally and function as a team of lobbyists.

These suggestions are in line with what happened during the 5-year period decades ago when no SA existed. Unfortunately, our history also shows that both ideas are deeply flawed. In 1970, the Program Board and the MCGB-equivalent came under fire for taking 6 months to fill a key position and for general disarray.

The JCFS was also not the ideal mode of student advocacy. A 1971 Hatchet editorial criticized the “endemic failure of the GW administration to seek student input in its decision-making bodies.” A news headline read, “Student-Faculty Relationships Stressed.” In 1975, JCFS actually voted in favor of creating a constitutional convention to form a new student government.

Even Katrina Valdes, the student co-chair of JCFS, is skeptical that JCFS could really function as the primary advocacy body for students. When listing the drastic changes that would need take place for that to happen, including installing a student representative from every school on the board and holding elections, it begins to sound an awful lot like the All-University Assembly proposal that was never able to get off the ground forty years ago. As a result, Gardner’s proposal doesn’t seem developed enough to ensure an outcome any different than the one of 1970.

I recently spoke to a friend who is a former senator in the SA and who, in theory, supports its abolition. He explained his position by describing the SA as a run-down house. You can do superficial repairs, but sometimes it’s better to just tear it down and start anew. I liked the analogy, but it’s not quite finished. Without a game plan set in place, once you tear the house down you’re just homeless. Certainly a run-down house is better than no house at all.

Corey Jacobson, a senior majoring in business, is a Hatchet columnist.

Editor’s note: This is a first in a series of columns that will examine the Student Association.