Student-athletes will need to make a difficult decision to return for another year of eligibility, but experts said athletic officials were right to allow another year of play.

The NCAA announced last week that spring athletes can come back for another season after the COVID-19 pandemic cut this year short. Sports law and management experts said the extra year gives senior student-athletes closure, but added that the potential influx in student-athletes next spring could financially strain athletic departments and limit recruiting opportunities.

“The NCAA made the right decision, but the implementation is going to fall on the student-athletes,” Helen Drew, a sports law professor at the University of New York Buffalo, said. “I think for most of the student-athletes, if you want to come back, you’re welcome to do so, but it’s going to be on your own dime.”

GW holds 191 spring student-athletes governed by the NCAA, including 45 seniors and four graduate students.

Athletic Director Tanya Vogel said in an email that the added year gives spring student-athletes a chance to “explore and evaluate their options.” Some student-athletes might return while “many” will follow through on post-graduation plans, Vogel said.

She added that men’s rowing and sailing, which are governed by the International Rowing Association and Intercollegiate Sailing Associations, respectively, will also receive another year of eligibility.

Vogel declined to say how the athletic department would handle the financial impact of the NCAA’s decision, adding that the department is “working collaboratively to make decisions in a timely fashion.”

For the 2018-19 season, GW allocated more than $12 million in athletic-related student aid and broke even on its roughly $31.6 million budget, according to data from the Equity in Athletics Data Analysis.

Ellen Staurowsky, a sports management professor at Drexel, said seniors will need to weigh the financial feasibility of returning for a fifth year, as well as their job or graduate school prospects should they opt out of the extra season.

“Financial considerations are going to be very high on the list for their families, and even today as we’re talking about this given the increasing unemployment rates which appear to continue to be going up,” Staurowsky said.

She added that coaches could divide scholarships to entice their strongest performers back and disincentive other athletes from returning by providing a lesser aid package.

“What we can anticipate is some athletes will get just enough for them to come back without a full package,” Staurowsky said. “You might see some other athletes who may not receive anything at all, and that’s going to be a message to them in terms of their standing on the team to begin with. Coaches will manipulate the latitude that’s given to them.”

Gil Fried, a sports management professor at the University of New Haven, said finances for athletic departments will be “really, really strained” if schools count on income from the NCAA and game attendance for funding.

March Madness continues to be the NCAA’s largest source of income, bringing in $867.5 million from television and marketing rights and $177.9 million from ticket sales during the 2018-19 season. Funds are then allocated to Division I schools to use for scholarships, sport support and funding travel, food and lodging for championships.

Because the COVID-19 pandemic axed March Madness this year, the NCAA expects to dish out $225 million to Division I schools, $375 million less than originally anticipated for 2020.

David Ridpath, an associate professor of sports administration at Ohio University, said some athletic departments have cut their programs in the wake of the pandemic, but that should be a last resort for most schools. Coaches and administrators should instead follow Iowa State’s lead and “cut the fat” from sports budgets by limiting travel expenses or taking voluntary pay cuts, he said.

Division I programs across the country have responded differently to the financial hardships caused by COVID-19. Old Dominion, a Conference USA school, cut its wrestling program and Iowa State, a Big 12 school, announced pay cuts and suspended bonuses and incentives for all coaches for a year.

“You should not want a sport to be dropped just so your sport can continue having excess,” Ridpath said. “That’s really what I think needs to happen. There’s certainly other ways to cut fat besides dropping sports. Dropping sports should be the absolute, absolute last thing to do.”

Ridpath added that schools like GW could bolster fundraising efforts to save scholarship money. The athletic department raised more than $166,000 in its annual Buff and Blue Challenge last year.

“Maybe starting a special drive for spring scholarships, and people are very giving at this time and that might even spur coach’s decisions to not take a salary or donate or cut a percentage,” Ridpath said. “That’s great public relations too.”

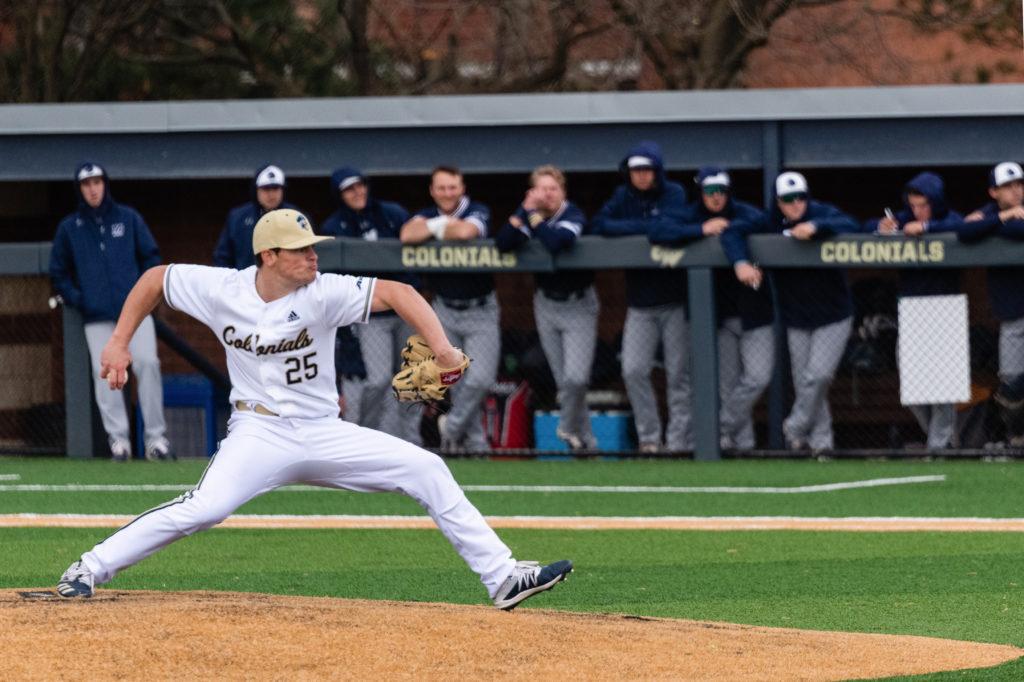

Experts said recruiting will also be affected by the extra year of eligibility. Schools will be allowed to carry more scholarship spots to accommodate returning seniors and new recruits, while baseball rosters will be expanded from their 35-member cap.

John Wolohan, a sports law professor at Syracuse, said coaches will need to halt recruiting trips overseas during the summer to limit the spread of the virus. International student-athletes compose nearly 16 percent of GW’s student-athlete population.

He added that the coaches may need to offer spots on teams without ever seeing them compete live, relying on video.

“A school like George Washington or a Syracuse, we have a large international population at our school and all of a sudden, those students aren’t going to be showing up next year just because of the pandemic and world conditions and our borders open where people can travel,” Wolohan said. “I think it’s going to impact international recruiting of athletes tremendously.”

Belle Long, Roman Bobek and Tara Jennings contributed reporting.