Updated: April 28, 2015 at 3:17 p.m.

GW will fund seven of its schools by the number of students taking classes in that college starting next year, marking the one of the biggest changes to how the University funds programs since officials began unveiling a new budgeting system.

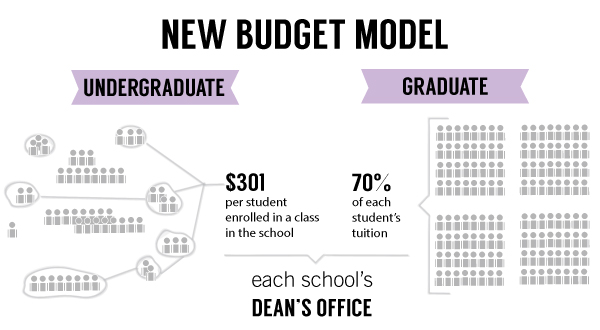

The University’s overhauled budget system formalizes how cash flows throughout most of GW’s schools. The update will grant each school’s dean’s office $301 for every undergraduate student in a class, as well as 70 percent of any on-campus graduate students’ tuition dollars.

The University is reliant on tuition for about 75 percent of its revenue. Schools previously received funding based on how many students were majoring in a college, Vice Provost for Budget and Finance Rene Stewart O’Neal said in an email. But because students can take classes outside of their majors, that system did not give the fullest picture of how many students were taking classes in a specific school.

“This amount will be given to the school to cover the majority of undergraduate instructional costs,” Stewart O’Neal said.

Faculty leaders said that the old system encouraged schools to have students majoring in the college to take courses outside of the school, because a school would receive funding for that student but would not have to take on costs to teach that student. The new system, though, will incentivize schools to create popular classes because they would boost revenue for the school.

Stewart O’Neal said the budget model will make it easier to understand how money can be spent in each school.

“The new budget model’s objectives are to outline clear and understandable fiscal rules, promote prudent stewardship of resources and ensure accountability,” she said.

Stewart O’Neal added that the new budget model will serve all GW schools except the law, public health and medical schools because they each manage their own budgets. The rest of tuition revenue will go “back to the University to cover the costs of centrally provided services,” like GW’s libraries and Student Health Service.

Stewart O’Neal said offices will receive 80 percent for off-campus graduate instruction and 85 percent for online graduate instruction, to encourage the creation of new online courses and programs.

Anthony Yezer, an economics who helped shape the University’s budget model as a former chair of the Faculty Senate’s finance committee, said the new model is “more transparent” and allows anyone to determine how much money a school will bring in by offering a certain course.

The University created a unified budget model for the University last year, which made spending rules for most of GW’s school. The model let administrators plan for unanticipated expenses for the first time.

Yezer said the budget system is “based largely on what school you were in rather than who’s teaching you.” Lecture-style classes, like introductory courses to economics and political science, will bring in high revenue for the school they’re housed in, Yezer added.

Certain classes, like economics courses, are taken by many students from several different schools — a point which Yezer said the University is still working on to create a method for sharing that revenue.

“Quite frankly, the difference is one third of my colleagues in economics are budgeted to the [Elliott School of International Affairs] dean,” said Yezer, a professor in the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences. “So there has to be a fix up for that.”

In November, the University announced that schools would receive 27 percent of the amount earned through a combination of funds from the University’s central budget and a government subsidy known as an indirect cost recovery.

Charles Garris, a mechanical engineering professor and chair of the Faculty Senate’s executive committee, said the new model will also allow administrators to see how changes in the amount of money the University has available in a certain fiscal year will affect future budgets.

He said the forecasting capability will help administrators make financial decisions and make the impact of decisions more clear.

“Sometimes with a predictive model, you find things that people think are very important, and they turn out not to be so important,” Garris said. “And sometimes you find things that shouldn’t be important, but all of a sudden, lo and behold, they are.”

Donald Parsons, an economics professor and member of the Faculty Senate finance committee, said a budget model gives universities the opportunity to prioritize managing its finances. Otherwise, the University would have no safeguards helping it avoid irresponsible spending.

“In a world where you’re doing it by the seat of our pants gives the underlying organization no direction of what you want,” Parsons said.