The University’s financial foundation grew on pace with those of other schools nationwide last year, as healthy markets bolstered investments that GW uses to pay for scholarships and faculty salaries.

GW’s endowment gains of 14.6 percent last year were just slightly smaller than those of other universities, according to a survey of more than 830 schools from the National Association of College and University Business Officers. Among GW’s competitor schools, Duke University saw returns of about 20 percent. GW kept pace with peers like New York and Boston universities.

Endowments larger than $1 billion saw average gains of about 16.5 percent, the largest of any group, according to the survey.

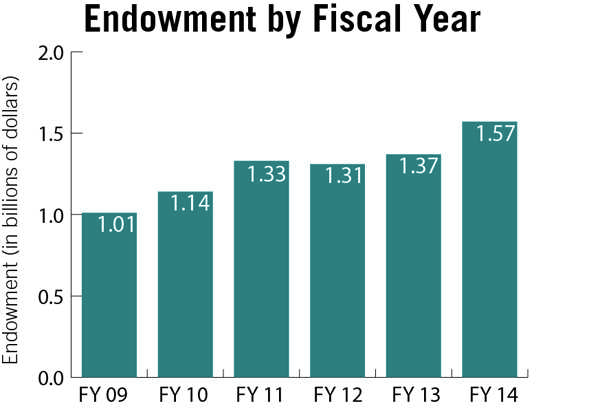

The University’s endowment now totals about $1.57 billion. The 15 percent increase last fiscal year is the first time in three fiscal years the fund has seen double-digit growth.

Schools nationwide saw their endowment returns total about 15.5 percent because of healthy markets and a strengthening U.S. economy, said Ken Redd, the director of research and policy analysis at NACUBO.

Schools also took out an average of 9 percentage points more from their endowments last year, according to the report. That “hefty increase” is good news for students, Redd said. GW has taken out about 5 percent every year for the past several years.

“It’s a very, very good story for students at most campuses. They’ll be the primary beneficiaries over the next years or so,” Redd said.

Over the past five years, the University’s financial base has grown by nearly half a billion dollars, helping it fund construction projects, hire more faculty and award scholarships. But nine of GW’s peer schools have larger endowments.

Redd said about three-quarters of the schools NACUBO surveyed, including GW, increased their spending in areas like faculty research and endowed department chairs.

He also said it’s normal for schools to see the gains from their endowments “vary” depending on where their money is invested and the “balance of stocks and bonds.” GW saw its largest increases in state bonds, federal bonds and international stocks.

University spokeswoman Maralee Csellar declined to say whether officials expect to see GW’s endowment grow again next year.

“All markets go through cycles. We will continue to use a long-term investment strategy,” Csellar said. “It is always good when there are double-digit returns.”

GW’s endowment grew by about 5 percent in fiscal year 2013, a smaller amount than its peer schools. Returns fell by 2.25 percent the previous fiscal year.

William Jarvis, the managing director at the Commonfund Institute, said schools will likely see gains next year, though growth can be hard to predict because it often depends on external or international factors, like the result of negotiations between Greece and the rest of Europe.

Jarvis said it’s important to take a long-term view of gains and losses in an investment portfolio, as schools that have investments in multiple areas can help protect themselves against losses in the long run.

“You have to remember that the goal of the endowment is to have as many dollars as possible every year, ideally growing year to year, to spend for the purpose donors gave the money for,” Jarvis said.

Investing in areas like hedge funds instead of just the stock market, for example, can protect schools from the “full storm winds of all gains and losses” if the market doesn’t perform well, Jarvis said.

“There’s no way to get a high return without exposing yourself to higher levels of risk. What you’re looking for is a structured portfolio that does OK when markets advance but loses less when markets decline,” Jarvis said.

At the end of December, officials announced that Arlington, Va.-based firm Strategic Investment Group would manage the University’s endowment. Officials decided GW would outsource the management of its endowment last spring, eliminating seven positions in its investment office.

Strategic Investment Group declined to comment on GW’s returns. The decision to outsource makes the University’s investment portfolio one of the largest in higher education to be managed by an outside firm.

Jarvis said schools have increasingly hired outside groups to manage their investments for about the last decade, as schools “desire more complex portfolios.” He said it’s hard to tell whether an outsourcing decision will lead to endowment growth.

“There are so many models of outsourcing,” Jarvis said. “Some firms may not have full discretion and may make recommendations. On the other end, some have complete discretion where the school said ‘You do it all.’”