Faculty leaders expanded professors’ academic freedom protections to cover work around the world Friday, although the policy would not protect faculty from foreign government censorship.

The University has increasingly looked for ways to shield professors and students from limits on teaching, research and class debates as it extends its reach in countries like China, where the government restricts public discussion of topics such as the Taiwanese government, Tibet and the Dalai Lama.

The stamp of approval is the first in what will be a series of changes to the Faculty Code over the next year, which Board of Trustees chair Nelson Carbonell said would be important as the University focuses on globalization.

Executive Committee chair Charles Garris said though the measure is largely symbolic since the code would not stand up in international courts, it would help professors feel secure and supported.

“No matter where you are in the world, even if you’re teaching a course in Saudi Arabia or in China, or wherever, GW recognizes your right to academic freedom,” said Garris, who helped craft the resolution as the former chair of the professional ethics and academic freedom committee.

The resolution also affirms the University’s stance on maintaining academic freedom for professors studying Chinese policy, who could have cause to fear censorship by the Confucius Institute, a Chinese government-funded center that promotes the country’s language and culture around the world.

Confucius Institutes, which are housed on over 400 campuses worldwide, have jump-started the debate about academic freedom this year, after schools like the North Carolina State University revoked an invitation to the Dalai Lama to speak on campus out of concern that the visit could hurt its budding relationships in China.

GW opened a Confucius Institute last April. Since then, leaders like China’s only female vice premier have visited campus.

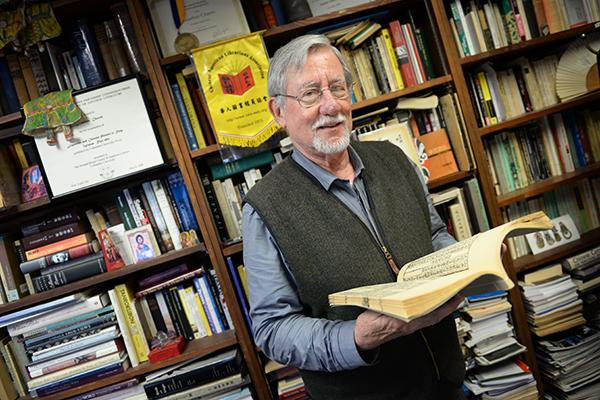

Ed McCord, director of the Elliott School of International Affairs’ Sigur Center for Asian Studies, said the Confucius Institute’s programing supplements the center’s programming, which is more focused on policy analysis.

McCord said restrictions are mostly enforced by the university housing the institute itself because it worries about losing funding if it angers the Chinese government.

“I personally think there’s no threat to academic freedom having a Confucius Institute on our campus, but that is what you see in the press,” McCord said.

The University has declined to say how much funding it receives from the Chinese government to run the institute, but Texas A&M University and the University of Utah each received about $100,000 to launch the centers on their campuses, according to contracts obtained by Bloomberg News.

Provost Steven Lerman has pointed to the Confucius Institute as a central part of GW’s plans to grow its presence in China, as it partners GW with Nanjing University. All Chinese universities are government funded.

When GW announced the center would launch on campus, former dean of the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences Peg Barratt said she would support the program because other institutions, specifically the University of Chicago, had also started them.

Last month, more than 100 professors at the University of Chicago petitioned the Council of the University Senate to terminate the contract with Hanban, the government entity that oversees the centers, citing academic freedom concerns.

“If the administration says, ‘Well, we have this Confucius Institute, maybe we shouldn’t bring the Dalai Lama to campus because it might offend them,’ you can make that decision, but that is in the University censoring, not the Confucius Institute,” McCord said.

McCord said the Sigur Center mostly focuses on Asian policy issues, and if it tried to limit what professors discussed in class, the University would likely reject the center.

Jonathan Chaves, a professor of Chinese, said he opposed the Confucius Institute because faculty who teach about topics like Taiwan or Tibet risk censorship.

“The Chinese Communist Party is an entity which does not encourage freedom of expression in its own country, in its own education system,” he said.

Columbian College of Arts and Sciences Dean Ben Vinson, who is also the director of GW’s Confucius Institute, said the University would not allow the partnership to strip faculty of their academic rights.

“We will continue to work to fulfill the mission of the Confucius Institute, which promotes the study of Chinese language and culture, supports Chinese teaching through instructional training and certification, and enables the prosperous growth of research on China studies,” he said in an email.