It was not long ago that students protested at the Marvin Center dedication, believing, as The Hatchet editorialized that day in 1971, that “the name Cloyd Heck Marvin will insult many users of this Center, especially the black students whose parents were not allowed to attend GW.” To this day, the mention of Marvin’s name brings a mixture of revulsion and admiration from those who studied and served under him.

Before writing my book, “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit: A critical portrait of Dr. Cloyd Heck Marvin,” I asked President Trachtenberg how he felt about a suggestion to rename the Marvin Center. He responded quite rightly that we should repudiate bad behavior not by “taking names off buildings” but rather by “the example we set for those who follow us.”

But perhaps taking a name off a building would be an example for those who follow us.

The story of Dr. Marvin is revolutionary and scandalous, and his legacy must comprise the good and the bad. In his 32 years as president of GW, Marvin doubled the size of the student body, tripled the size of the faculty and increased the endowment nine-fold. He expanded a campus that comprised three buildings and several adjacent townhouses to over a dozen city blocks with a renowned medical center and law school.

The faculty may have grown larger, but they were never assured of tenure or academic freedom throughout Marvin’s term in office. In his first 15 years, more than 100 professors appealed their cases to the American Association of University Professors, calling for an immediate investigation into the purges of the faculty. Over time, Marvin governed with less friction, but many faculty members neither respected nor liked Dr. Marvin.

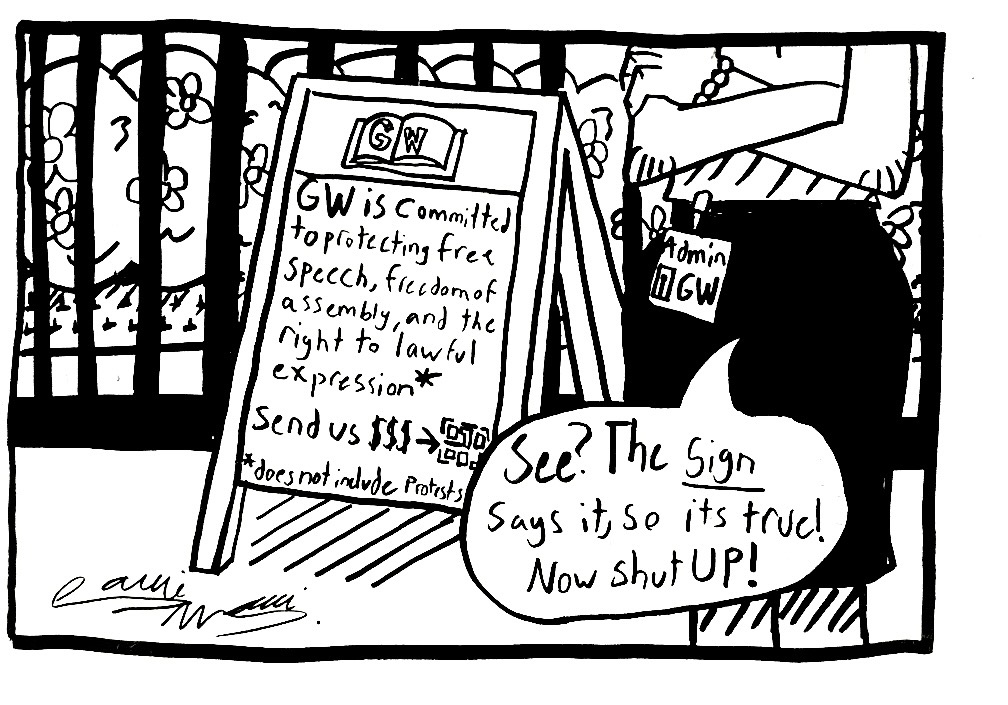

The students may have been more numerous by the end of his term, but many of them can still remember how Marvin suppressed the Liberal Club and the peace strikes, banned a number of literary publications and fired or suspended the Hatchet board of editors at least six times for criticizing the administration. Marvin’s tacit support of segregation, his attempt to kick Hillel off campus and his constant manipulation of the Board of Trustees caused many to resent his heavy-handed policies.

In 1946, Marvin attempted to expel a student who protested outside of Lisner Auditorium on opening night because the student opposed Lisner’s whites-only racial policy. A Hatchet editorial “Expulsion – Be Damned!” summed up the student response to the attempt; he abandoned his efforts after a sitting U.S. congressman condemned the action.

In 1970, a group of students seized the Student Union building – not yet named the Marvin Center – and renamed it the Kent State Memorial Center, after an incident at an Ohio university that left four students dead. A building that is the center of student life on campus should reflect student values. Perhaps a “Kent Union” would be more appropriate than a “Marvin Center.”

Marvin’s persecution of liberals among the faculty, his well-documented support of segregation and his constant disregard for the civil liberties of students make his legacy one that should not be memorialized on so prominent a building as this one. If we want to set an example for future generations, we must always remember, but not celebrate, the sins of our forefathers.

-The writer, a senior, is the former Hatchet Research Editor and author of “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit: A critical portrait of Dr. Cloyd Heck Marvin.”